Much like gangster films, the boxing movie exists in a seductive subculture full of captivating figures who sometimes walk the tightrope of the law. By allowing artists to explore class, race, poverty, masculinity and violence, it is a genre that allows our sadistic eye into the heart of darkness.

The Set-Up (1949)

The year is 1894. Mike Leonard and Jack Cushing – two ordinary professionals unlikely to be remembered for their pugilistic skills – are standing in what looks like a barn with a retractable roof in West Orange, New Jersey.

This is Black Maria – the world’s first movie studio – owned by Thomas Edison and built for the sole purpose of creating productions for his Kinetoscope. The ‘bout’ was to be six one-minute rounds, all due to the technological restraints posed by the Kinetoscope. It was designed to pose as a real contest whilst being pre-arranged, right down to the knockout climax.

Edison’s Black Maria

A small ten foot ring was created for the fictional contest with the Kinetoscope in a fixed position square onto the ring: to this day the angle of choice for TV broadcasts of professional bouts. The scripted slugging was debuted for fans at the Rector-Latham Kinetoscope parlour in New York and the first boxing film was released into the world.

Over a century later boxing and cinema have remained symbiotic: the latter completely seduced by the former.

One Night in Miami, Regina King’s outstanding adaptation of a Kemp Powers play is about the night Muhammad Ali (still going by Cassius Clay), Malcolm X, Sam Cooke and Jim Brown celebrate Ali’s ascent to world heavyweight champion after knocking out Sonny Liston. The film was this year nominated for three Academy Awards. It is the climax of a resurgence in the boxing movie that started with 2010’s The Fighter and has meandered through Southpaw, Bleed for This, Jungleland, Hands of Stone and the Creed movies.

ArrayThe attraction has been mutual. Some of boxing’s biggest bouts in recent years have been screened in cinemas across the US. The Deontay Wilder-Tyson Fury clash played around the US in cinemas and so did Floyd Mayweather’s later day blockbuster fights. On this side, Anthony Joshua fights have also been given the cinema experience in recent years.

So why does cinema’s boxing obsession endure? What makes it that much more cinematically alluring than football or basketball or NFL? The answer is the same as why we love gangsters and cowboys and hard drinking private detectives. For boxers live outside societal norms. They embody a rebellious, renegade life. They become humanity’s eye into the heart of darkness.

The Champ (1931)

The reality is simple – boxers are people who are paid money, sometimes a lot, but often very little, to hurt another human being in front of a mob of baying spectators. Boxing is an underground subculture, one that is simultaneously hugely popular yet strangely niche. On screen it has acted as a kaleidoscope for enduring themes such as race, class and masculinity.

The film we have to thank for the sport movie archetypes of today is King Vidor’s 1931 pre-code picture The Champ. The tale of Champ Purcell, a one-time star brought down by his love for the bottle who tries to redeem himself in the eyes of his son and reclaim the glories past. It follows clichés now ridden to death over the subsequent ninety years of sports movies – not necessarily interested in the fighting, but rather the man behind the gloves.

These are stories of self-destructive souls that know only pain and violence, and who are broken by societal expectations of masculinity. Themes that boxing movies would revisit time and time again over the next century.

The Set-Up (1949)

The success of The Champ whetted Hollywood’s appetite for redemption stories. A veritable gold rush of depictions of the sport came in the 1940s during the golden era of noir. Raoul Walsh’s Gentleman Jim which starred the prettiest of pretty boys in Errol Flynn as boxing pioneer James J. Corbett was the first of this pack.

Whilst not the depiction of the internal psychological struggle that was so raw in The Champ (it was made during World War II where cinema was focussed on uplifting pictures), Gentleman Jim featured far more sophisticated fight scenes, with techniques still seen in boxing movies today, such as the POV shot before landing a knockout blow.

But it was 1949’s The Set-Up that really captured what was so alluring about the sport. It had nothing to do with two men belting leather against each other and everything to do with the type of men boxing attracts. In the case of this grimly bleak noir, it is bent promoters, regretful fighters, deadly gangsters and bloodthirsty fans. The Set-Up takes place on the day of a journeyman’s final fight – a fight that has been made painfully clear to him that he is expected to take a dive.

This is the fighter as an honourable diamond in an ocean of tar. He is trapped in the existential quandary of throwing the fight and with it his dignity, or winning and being left at the mercy of mobsters.

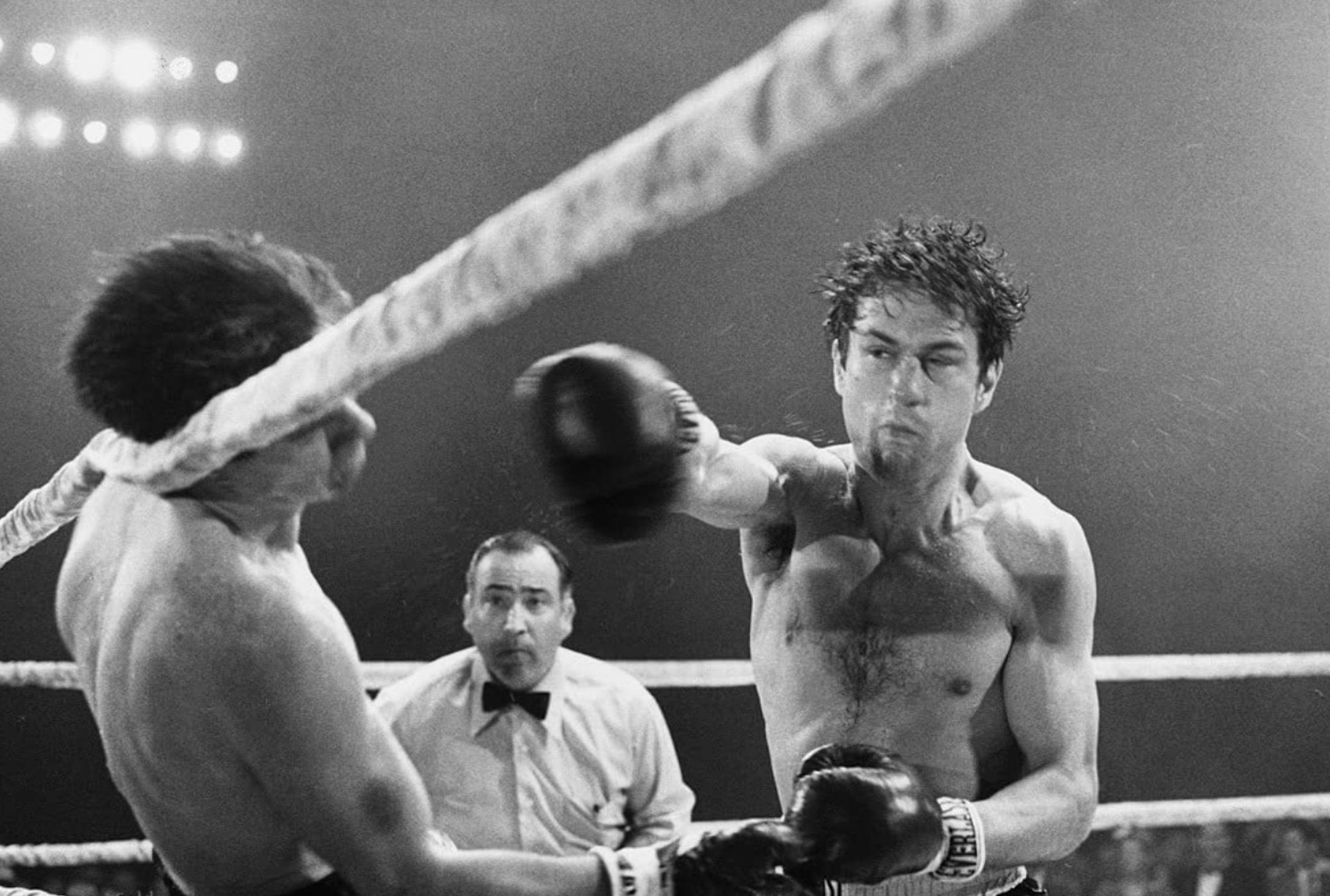

Behind the scenes of Raging Bull (1980)

Throughout cinema’s history, the boxer is an archetype, the man who faces off against the world and, importantly, himself. But the boxer comes without the redeeming characteristics of the renegade cop or white-hatted cowboy.

The boxer is emotionally and sexually dysfunctional, his communication with the world through violence and pain. This is most effectively portrayed in John Huston’s masterpiece Fat City and Martin Scorsese’s virtuoso biopic of Jake LaMotta, Raging Bull. They are two rage-fuelled films that show boxing as the sport of the unmentionables – the immigrants, the poor, the ill.

Scorsese apparently had no interest in boxing or sport in general but he uses LaMotta’s story to channel his own thoughts on masculinity and violence and addiction. It’s notable that at the time of Raging Bull’s making the director was in the throes of a heavy cocaine addiction.

LaMotta is shown to live his life in the same way he fought in the ring – with an animalistic desperation that has him pummel both his opponents and the love of his life. Raging Bull is a brutal movie, both for its nasty depiction of ring violence and its portrayal of a brute of a man lost to the rage. It is told with beautiful expression, Scorsese surely borrowing from Sergi Eisenstein and Elia Kazan to build his psychologically torturous masterpiece.

Fat City is a similar descent into hell. It may be set on the opposite coast in sunny Stockton but it has the same angst, the same working class frustrations, the same struggle for meaning in an empty life. As a movie, it ‘gets’ boxing better than any other. It isn’t about contenders or champions, men who are destined to be something if all they had were given was a little guidance.

Fat City is about the working class boxer with the sport as his means to eat, drink and live. The small remuneration is nothing compared to the brutality they endure to provide for their families. There’s no bright lights or Vegas championship celebrations – you win: you go to the bar, you lose: you go to the bar.

It’s an unsentimental sport full of mean, hard men who see bodies to be used and abused to make a buck. It is this sadism that is partly why we love the genre so much, for it is as seductive as Mafia movies with their codes of omertà and molls in mink coats.

Twenty Four Seven (1997)

A British version of this is Shane Meadows’ Twenty Four Seven which stars Bob Hoskins as a Brendan Ingle-like figure who nurtures young boys in a decaying working class northern town. Meadows here though shows the positive impact boxing as a hobby can have on young men with nothing to do.

The complete opposite of this type of boxing film is Michael Mann’s Ali. Muhammad Ali is a figure so large, so recognisable, it’s almost impossible to draw the psychologically complexities.

Therefore, Mann elevates him to a mythic deity, who in the stunning final third in Zaire – at the pinnacle of his career – conquers the seemingly indestructible George Foreman with Godlike precision. Ali is the ideal man in the mould of what we have been told a man should be. He is an athletic genius, unafraid, charismatic, capable of outstanding violence and prepared to sacrifice anything for his beliefs – millions of men have lived vicariously through him and it’s this reverence Mann puts on screen.

Ali (2001)

Rocky is one of the most recognisable characters in cinema and is now a ubiquitous pop culture reference point. Before becoming a poster boy for American capitalism, Rocky was the underdog working class tale like the many boxing movies of the forties. Stallone mumbles like Brando and with his big hulking frame hunched with sadness and the weight of his duty, embodies the steel mills and car manufacturing plants of the Rust Belt of America decimated by recession of the early seventies.

This spirit survives through Ryan Coogler, who revived the character for the Creed films, and in the first of the series, Creed, explores the brutal horror of the American justice system, the intersection of race and class as young Adonis Creed can reap the rewards of his famous father whilst his girlfriend, a struggling musician, has no such privilege.

Cinema’s reverence for a fight outweighs the general public’s, boxing is not the world halting sport it used to be (though that may change if and when Anthony Joshua and Tyson Fury square off).

There is something innately spectacular about seeing boxing on the big screen. It’s not just the primal slaps of leather on flesh or the divine strength of man laid bare for all to see but the ability of the sport to be society’s mirror, for it to be a captivating interrogation of humanity’s darkness, a darkness that sees the fight film endure.