Palazzo Spinelli stands, a great solid mass, on the corner of via Nilo and via dei Tribunali, at the heart of Naples’s Centro Storico. Like many of the city’s oldest buildings it is a mishmash of architectural styles: the razed terrace at the back shrouds the remains of a 13th century Anjou donjon; in the middle is an elliptical courtyard based on the interior of the Palazzo Farnese near Rome, its centrepiece a glazed maiolica clockface; the frontage is fairly nondescript, and certainly doesn’t hint at the riches within.

This is the way it is round here. Naples doesn’t tend to flaunt its riches, well its non-edible ones anyway. Intricate frescoes and sweeping staircases are glimpsed, tantalisingly, through cracks in gates or between slowly closing doors. The only crowds outside are those queuing for Sorbillo, one of the city’s most famous pizzerias, which is just across the road. Like most palazzi in the centre of Naples, Spinelli was built as the eponymous urban residence of an aristocratic southern Italian family. Today it is a tumbledown warren of private dwellings, big and small.

Palazzo Spinelli di Laurino

The first night I visited, it’d been raining. Uneven cobblestones glistened beneath a jumble of parked cars in the courtyard. I was there to have a drink with Nathalie Heidseick, a French writer who has been coming to Naples since the early 90s. Nathalie came across Spinelli while in town interviewing refugees from the war in Yugoslavia. She fell in love with the place and rents two apartments on the second and third floors. One for business, the other for pleasure.

We were a small party. Over wine and bacon-flavoured crisps we discussed the mounting crisis. Some believed Italy’s acute suffering had conspiratorial roots, being a punishment meted out by America for the country’s close economic relationship with China. “Think about it,” a wide-eyed Lorenzo implored, “who will be the winner from all this… Trump!” “It makes sense,” someone else mumbled.

We were a small party. Over wine and bacon-flavoured crisps we discussed the mounting crisis.

Later, walking back to my apartment through the narrow streets, drunk and a bit high, past groups of rowdy teenagers huddled outside bassi, from which wafted the seductive smell of frying onions, I stopped and congratulated myself that, after so many years of wanting to, I was finally doing it, I was living in Italy. I wasn’t unconcerned by the escalating situation in the North, but I believed it would soon dissipate.

Three days later, the whole country was in lockdown. Given the opportunity to move from my cramped apartment to Spinelli’s high-ceilinged piani, I packed my bags immediately. Noisily dragging them back from whence I had come a few nights before, I was clapped (ironically?) by a man outside a bar—I looked like I’d arrived for a holiday just as everything was going to hell. In a way I had.

Naples’s centre hasn’t been hollowed out by gentrification and is still resolutely popolare. Despite being entirely UNESCO-designated, due in large part to its intact ancient grid system, it is still very much a working neighbourhood. The streets are filled with greengrocers, bakeries, fishmongers and butchers. Emptied of tourists, it still felt alive, though a little cowed. Neapolitans are tactile even by Italian standards, but people were giving one another a wide birth—it felt like I was back in London!

I would be sharing my gilded cage with two cats, Cecil and Enzo. Their sustenance was the real reason I was there. Any company, however sentient, is to be cherished in these times. As is the internet. I was able to move very smoothly from teaching face-to-face to online. My students, all digital natives, adapted with supreme ease. Whenever my connection lagged, I cursed the millions of teenage boys locked in their rooms playing Fortnite. A couple of weeks ago, before announcing a new decree, Prime Minister Conte called on Amazon and Netflix to reduce HD-streaming in order to allow more people smoother connections.

I would be sharing my gilded cage with two cats, Cecil and Enzo. Their sustenance was the real reason I was there.

The one thing everyone misses is pizza. Its massive absence belies its inches. A few of my students have attempted homemade versions, but these are usually sad floppy affairs: doughy changelings whose nearness to the real thing only exacerbates the feeling of loss. Thankfully there is a thing called pasta that can be easily prepared at home. After a few days with just cats, I was craving human company and invited my friend Antonio, who’d I only met a couple of times, over for dinner. He too was locked down alone and, since I had two spare bedrooms, I asked if, well, he might like to join me in purgatory. Dear reader, he said yes.

Not only is Antonio an eloquent Anglophile, he is also, like me, a New Wave nut. Our days were spent apart, working, writing or reading, but we would converge in the evenings to eat, drink and listen to the Smiths. He is a fount of local knowledge, as well as an arch cynic. Seeing the number of people outside walking dogs, he muttered something about them having been bought on Amazon. Up and down the country, musical performances from balconies have gone viral, and we have our own cantante, who pops out every evening at six like a Brylcreemed cuckoo clock. Conveniently he has a new CD, which he plugs in between belting out Neapolitan and patriotic hits. It’s a testament to national spirit that the latter are so enthusiastically sung, Naples isn’t famed for its love of the Italian state.

Up and down the country, musical performances from balconies have gone viral, and we have our own cantante, who pops out every evening at six like a Brylcreemed cuckoo clock.

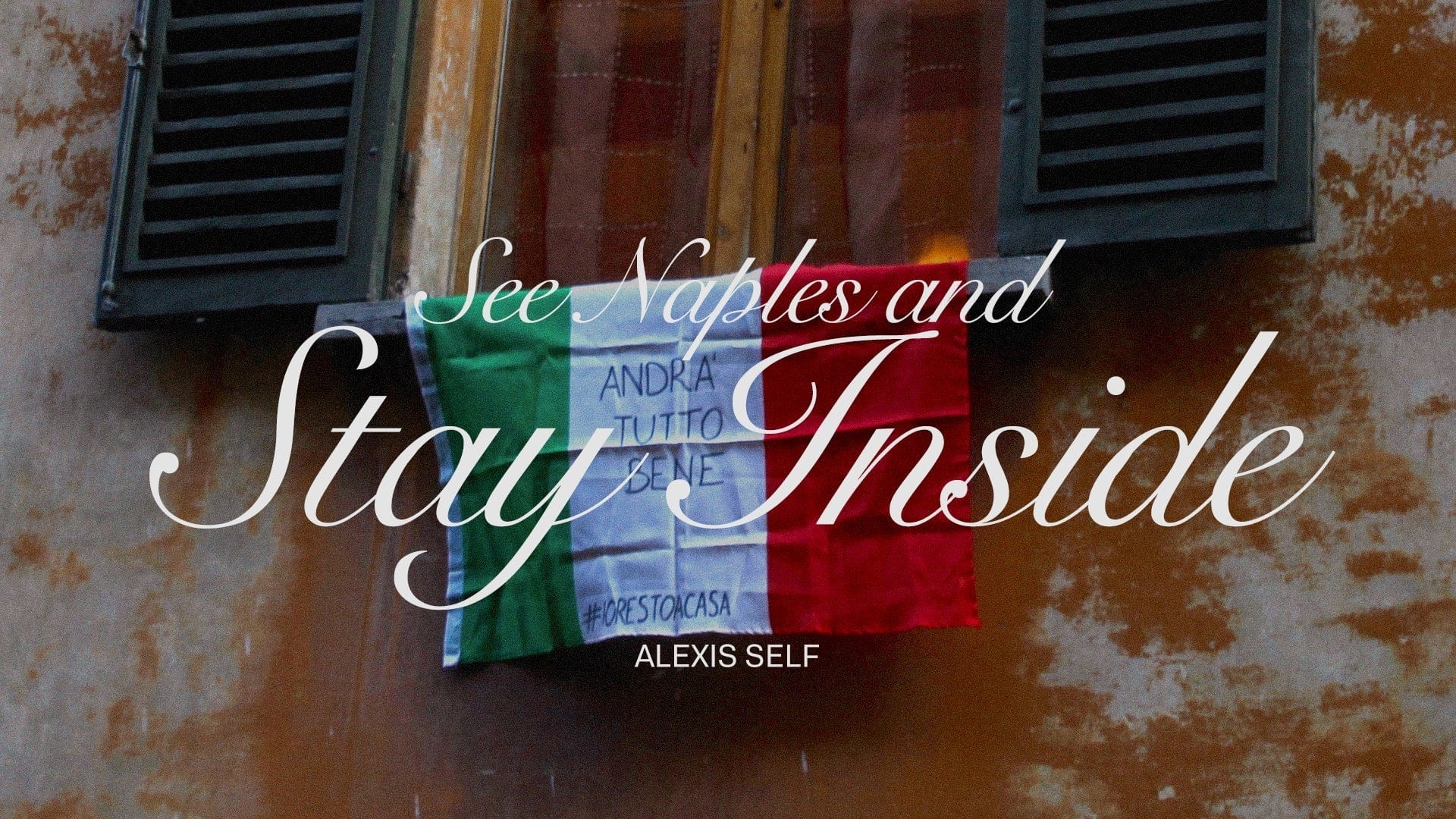

All over town, Tricolore flags are draped from windows, many emblazoned with the words ‘Andrà Tutto Bene’ (‘everything will be alright’), the quarantine mantra. I hope they’re right. Unlike in the UK, Italians aren’t allowed out to exercise and, even if they were, in Naples there are hardly any public parks. A trip to the supermarket contains the very real threat of being asked by a policeman or soldier to present a slip of paper with your personal details. I am very lucky to have some outside space, a roof terrace, in which I can walk in circles.

Quarantines have a storied history on this peninsula. Indeed, the English word comes from the Italian quaranta giorni (40 days), which was how long plague victims were kept apart from the population. This number was chosen for its religious connotations. A local padre has begun saying mass over megaphone. His sermons compete with the sounds and smells of cramped domestic life that drift up around me into the Mediterranean sky. In the distance Vesuvius’s twin peaks nobly loom, they too are waiting. For what, no one knows. I hope, of course, that every country, city and town recovers from this, and that life will spring again, once more eternal-ish. But I hope, most of all, that Neapolitans will be allowed out soon, they’re not used to being cooped up inside.