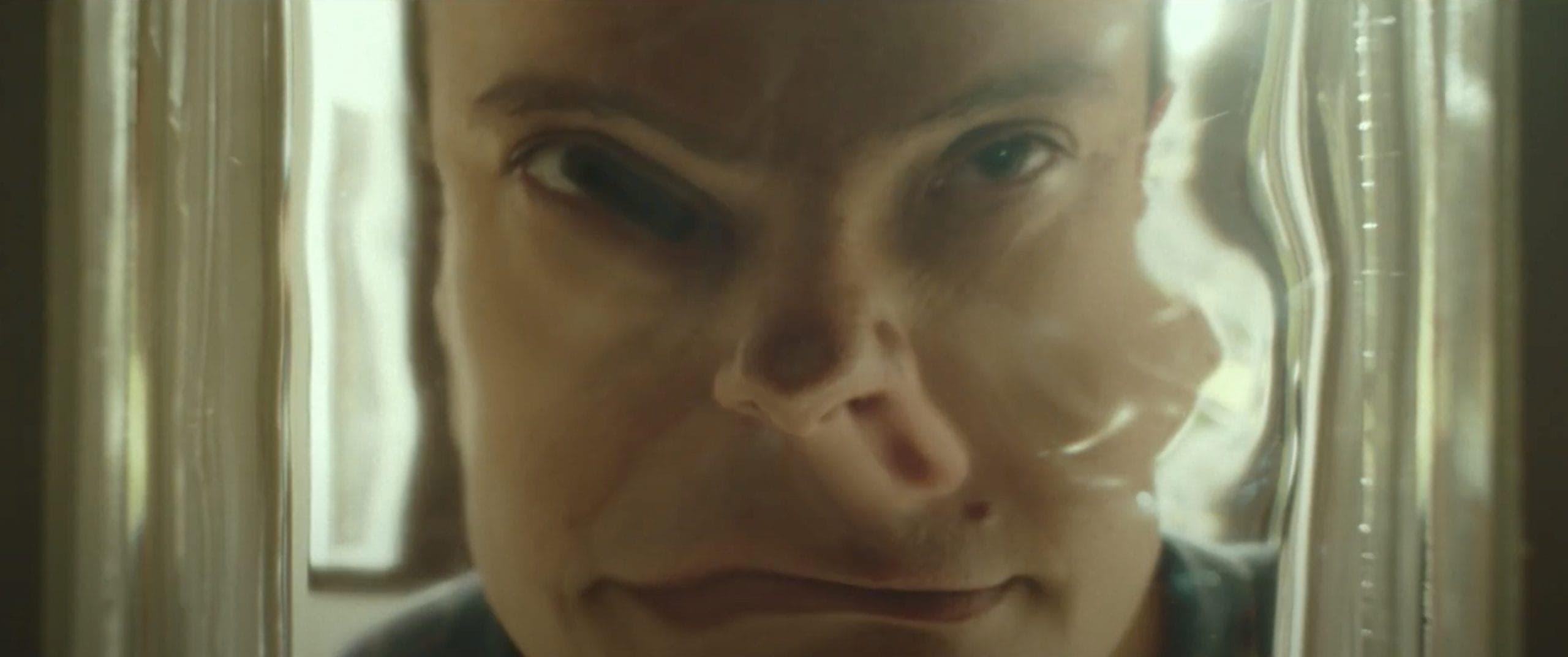

Bad Tales opens with a series of dreamy shots of an Italian neighbourhood. They look could almost be an archetypal American suburbia, but something is off. The atmosphere is tense and sinister. We can almost see the stultifying heat and every scene is accompanied by a soundtrack of rattling cicadas.

The stylish cinematography takes the rich nostalgic look of an American teen movie and saturates it with sickly colour. Everything appears at once too bright and too pale, as though the screen were covered in a grimy layer. It’s a style that fits the film’s bleak twist on the coming-of-age movie.

A narrator tells us he found the diary of a girl and began to read it. When the entries abruptly stopped, he decided to keep writing it. The story that follows, the narrator says, was ‘inspired by a true story… inspired by a lie’ that was ‘not very inspired to begin with’. These are the Favolacce, the fairy tales of the Italian title.

ArrayGradually, we’re introduced to a cast of characters. There is young Viola and her unhappy parents. There are Viola’s cousins Dennis and Alessia and their unhappy parents. There is the silent and pale Geremia and his unhinged father Amelio. Finally, there is the heavily pregnant teenager, Vilma.

What follows is less a collection of stories than a series of loosely connected vignettes.

Amelio tells his son Geremia to say goodbye to their dog before loading it into a pickup truck and taking it to be put down. Vilma squeezes breast milk onto a cookie and shares it with Dennis. Dennis’ dad holds his son upside down in the garden while he chokes on his dinner and his sister Alessia cries.

Two of the fathers leer at a woman and list all of the ways they would like to violate her. Dennis looks through a window and sees a man masturbating in the garden. Then he walks to a swimming pool with a young girl. ‘I really feel like fucking,’ he says. Later, we learn he has been building bombs in his bedroom.

It’s easy enough to list the scenes this way. Less easy is putting them together into a coherent order.

A generous viewer might hold that this is the point: these are lives that do not amount to neat stories, full of senseless lust and violence. Another viewer may start to grow bored.

A recurrent theme throughout the vignettes is the violent tendencies passed down from one generation to another, usually from father to son. When Amelio watches his son Geremia doing doughnuts in a pickup truck, he screams, ‘You take after me,’ and the words seem both a hopeful observation and a command.

It seems the D’Innocenzo brothers have no shortage of ideas for ways to show us the bizarre things men do, but where they fall short is showing us why they do them.

In one moment that appears to be a manifesto, Amelio turns to his son and says, ‘Do you see how strange life is?’

ArrayWe viewers do see it. But when life’s strangeness confronts us, we try to make sense of it, however futile that endeavour often turns out to be. When it comes to making sense, the D’Innocenzo brothers give us nothing to work with. There are no motives here. There is no history but the shared and general history of violence that repeats itself in every generation.

At the film’s end, when Vilma and her boyfriend drown their baby and kill themselves by jumping off a balcony, it is hard to feel shocked or moved. The violence has become familiar while the characters remain strangers to us.

There is much to applaud in Bad Tales’ project: to depict childhood without sentimentality, and to depict the violent consequences of poverty without falling back on the trope of the heroic and noble poor. Bad Tales is not a film about the loss of innocence. Instead, it seems to argue, we are wrong to believe that innocence is ever there to begin with.

But there is too little humanity in Bad Tales’ characters to make them memorable. There are too few details to help the audience distinguish one angry, lecherous man from another. In the end, Bad Tales too often fails to distinguish itself from the lecherousness it seeks to depict, and watching the film can often feel like being let in on a teenage boy’s private fantasies.

‘It’s just weird,’ one boy says near the end of the film, shaking his head. ‘It’s all very weird.’

That point may be hard to argue with, but Bad Tales’ weirdness never quite comes to life. Fans of the twisted, strange, and perverse may find a lot to enjoy in this undoubtedly stylish film. But a viewer hoping to see a film willing to ask questions of that strangeness may be disappointed.