For an exhibition entitled Time Levitation — Christine Rebet’s first solo show in the UK, Parasol Unit’s last in its current London space — a non-linear approach seems fitting. We begin at the end, with Rebet’s most recent animation, ‘Breathe In, Breathe Out’ (2019).

‘I knew I wanted to make a work about metamorphosis,’ Rebet says, when I ask her how the idea germinated. ‘I’m always drawing, drawing, drawing.’

Through each iteration, Rebet runs down her theme with ink. Blood forms roots and spinal palm trees. Kimonos fold into fields, while cities unfold from books. A larva mutates into a magic mountain. Rebet returns time and again to the red and blue of our circulatory systems. Breathe in. Breathe out.

Accompanying the animation is a meandering, twanging raga — a suitable score, since in the Indian tradition this melodic framework is considered able to ‘colour the mind’. A phrase befitting the viewing experience. As I sit there watching moons mutate into machines, I’m projecting forward metaphors I might use for this piece.

The whimsical feet — hooves, claw, toes — which stroll across white space, I’ll say, are emblematic of Rebet’s instinct to tread lightly (the human feet wear flip flops and dainty kitten heels, the non-human feet walk on their digits).

Hallucinations, dreams, metamorphosis and metaphor, I will have thought — all these experiences involve the apparent perception of something not entirely present; and with Rebet’s work you’re so often translated between mental spaces, in crabwise evolutions.

Rhizomes grow into spindly apparatus puffing out smoke; the strolling feet reappear, though this time they are robotic. The film is grounded by the story of a monk’s spiritual journey as he descends a mountain, while the image progression — from natural to technological — suggests a different descent: our potentially devastating effect on the planet, in an era of globalisation and mass automation.

So Rebet and I descend, back down to the first floor, making our way to ‘Thunderbird’ (2018), which recounts the story of an ancient temple. It was believed that the god Ningirsu and his avatar the Thunderbird appeared to the Sumerian ruler Gudea in a dream, commissioning him to build a temple in his honour.

Rebet explains the Sumerian tradition of burying votive offerings and inscriptions, in order to prolong their lives, to be remembered unto distant days — and how this came true, when archaeologists from the British Museum discovered the site.

ArrayI can see the story’s appeal for Rebet. It’s a perfect storm of collapsed temporalities: the divine vision in a dream; Gudea’s architectural plans (buried for prosperity); their execution in the building; the temple’s ruination; the site’s excavation by archaeologists, and their re-excavation in Rebet’s own vision. All of these times are intertwined in the film’s five minutes and forty seconds.

Like Gudea, Rebet sets about forming a landscape where architecture can meet prophecy. Geysers erupt. A red sun — a bomb — falls to earth as the frenzied tremolo-picking of an oud starts up like a warning siren, as if prescient of all those bombs that have since fallen on the Middle East.

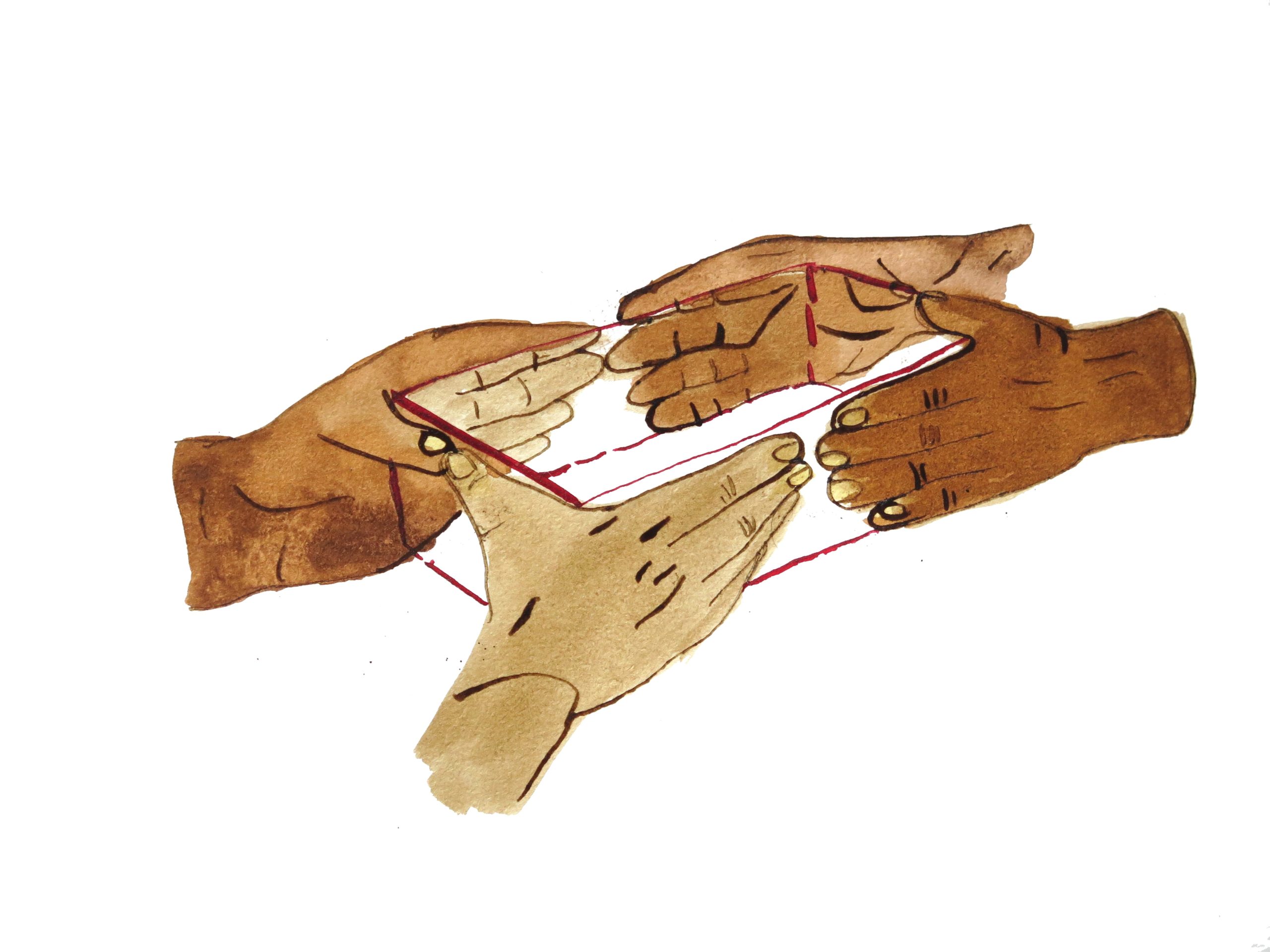

Between destruction and creation, we find hands — productive, culpable — which draw up architectural plans, mould bricks and echo those of their animator. The sweeping gesture of the thunderbird votive being formed gives way to the sweeping gesture of its uncovering during the archaeological dig. We’ve come full circle.

Rebet’s is a world in which things lay dormant and threaten to detonate: caterpillar to butterfly; suns to bombs; or the image, from ‘The Black Cabinet’ (2007), of grenades bumping around a roulette wheel, like the red buttons in our world leaders’ pockets. What thoughts might ignite when you follow a surprising connection off the mountain track?

We end at the beginning, with one of Rebet’s earliest works ‘Brand Band News’ (2005). Consider two girls in gingham dresses gunned down in a field, whose souls then hitch-hike in search of a new life. Whimsy metamorphoses to darkness. Time levitates.

‘The wind becomes a horse,’ Rebet explains. Of course. I’ve learned to expect nothing less.