Charlie Kaufman is one of the most celebrated screenwriters of his era, the man behind Being John Malkovich (1999), Adaptation (2002), Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), Synecdoche, New York (2008), and Anomalisa (2015). Kaufman’s is a singular approach: absurd, meta-, existential – the only word that will really do is ‘Kaufmanesque’. Now, he’s a novelist, and we expect his signature to be on every page of his debut Antkind. So, here’s how to play Charlie Kaufman Bingo and read along.

‘Mostly, we authors must repeat ourselves – that’s the truth,’ F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in 1933.

And to some extent, we want them to. Dan Brown wouldn’t be Dan Brown without the cliff-hangers and esoteric codes broken in city-wide treasure hunts. Dostoevsky wouldn’t be Dostoevsky without laughter and suffering, the sense that Crime and Punishment could be the title of any one of his books.

‘Gimmick’ is a word that consistently crops up in criticism of the work of screenwriter, director, and recently novelist Charlie Kaufman

On the one hand, it’s the highest compliment you could give a writer, to say their work is so idiosyncratic, recognisable and repetitious as to be easily imitated. On the other, we’re suspicious when writers rehearse the same themes over and over; it makes us uneasy, like we think they’re lazy for not coming up with anything new, that their work rests on a few gimmicks.

‘Gimmick’ is a word that consistently crops up in criticism of the work of screenwriter, director, and recently novelist Charlie Kaufman (mostly, I’d add, defending his oeuvre from the charge). Ideas, images, and formal concerns repeat themselves from script to script, and now, quite possibly, to novel.

For cultural theorist Sianne Ngai, the gimmick is a device that strikes us as ‘working too hard’ and at the same time ‘working too little’. It saves the writer labour, yet makes them labour all the more. Gimmicks are both ‘unrepeatable’, singular events and devices to be used a billion times over.

As Ngai points out, these apparent contradictions are ‘each about labour, time, and value – elements capitalism makes impossible to separate’.

The purported ‘gimmickiness’ of Kaufman’s work isn’t as simple as it might appear; it says something deeper about human experience

In light of this, I’d say the purported ‘gimmickiness’ of Kaufman’s work isn’t as simple as it might appear; rather, it says something deeper about human experience.

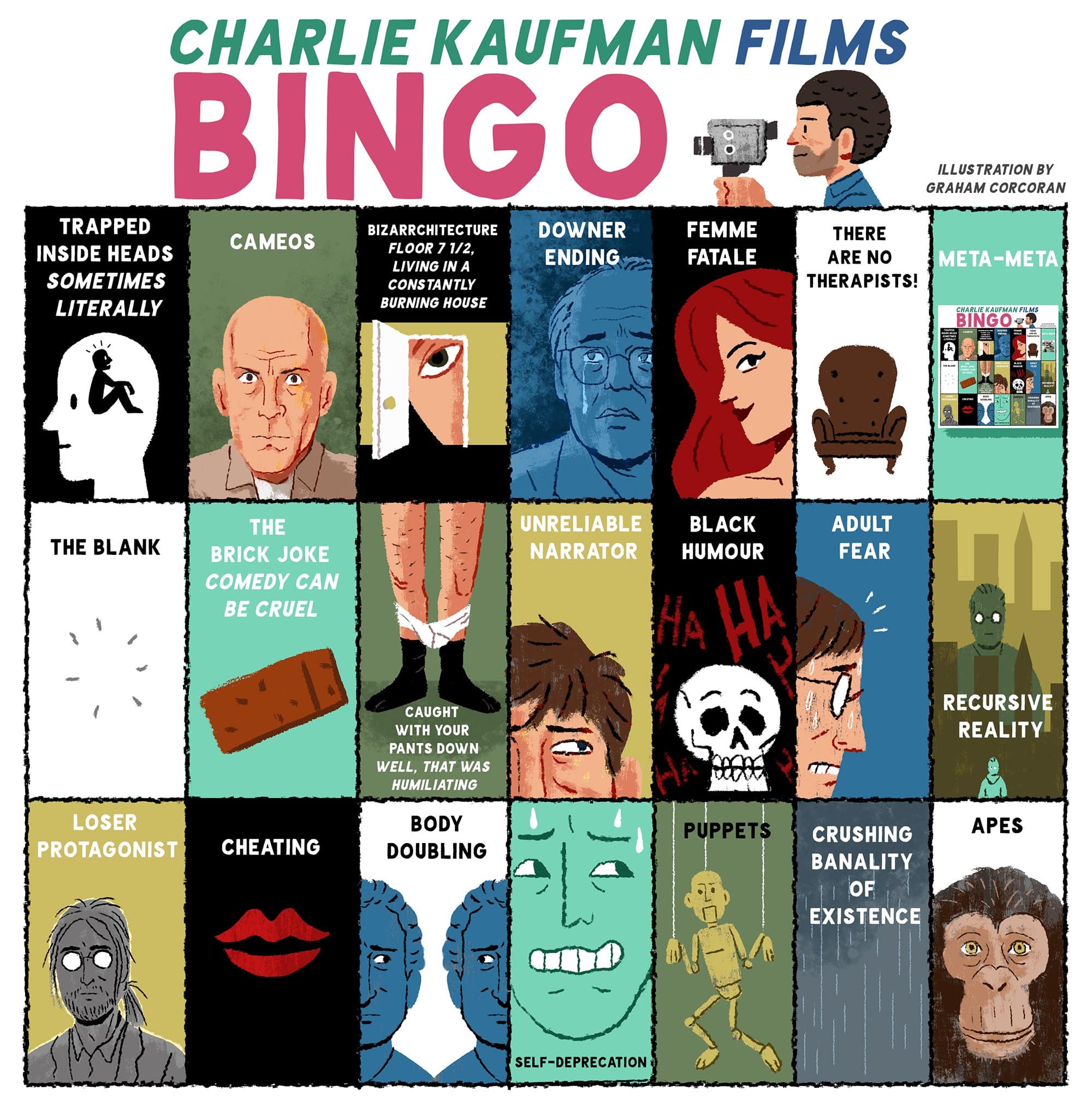

So here I’d like to consider the gimmick in the work of Charlie Kaufman, via a little gimmick of my own: with the release of debut novel Antkind coming up, I propose we might read it with a game of Charlie Kaufman Bingo.

ArrayTRAPPED INSIDE HEADS

Sometimes literally: see the portal that leads into John Malkovich’s in Being John Malkovich. One of Kaufman’s key themes is solipsism – the belief that only one’s mind, and the way it perceives reality, can be certain to exist. Antkind is over 700 pages long; written in first person, you’ll soon be all too familiar with the many neuroses of its

LOSER PROTAGONIST

(Ageing and impotent, optional.) ‘Loser’ isn’t strictly accurate, since Kaufman’s protagonists are often also simultaneously brilliant, exceptional. Take Synecdoche, New York’s Caden Cotard, who wins a MacArthur Fellowship. The award allows him to pursue the height of his artistic ambitions; at the same time, he seems to get a cheap thrill out of cleaning his ex-wife’s toilet. In Antkind, we follow a failed film critic called B. Rosenberger Rosenberg. You can bet he’ll be brilliant, but he’s also sure to be neurotic, solipsistic and

SELF-DEPRECATING

Kaufman’s characters don’t only deprecate themselves, but their creator. Adaptation sees Kaufman writing a self-loathing version of himself into the film, which begins with the voiceover: ‘Do I have an original thought in my head? My bald head? Maybe if I were happier, my hair wouldn’t be falling out.’

Antkind opens in similar fashion, with B. ruminating on his confected and unfashionable beard, which he thinks ‘says I don’t care a whit.’ Still, it is his ‘calling card’ – his gimmick, if you will. Sianne Ngai wonders ‘if we find gimmicks repulsive insofar as we find them attractive’ – even in Antkind’s opening pages, some similarly knotty thinking is going on with our protagonist and his hot-gross facial hair.

What’s more, being a film critic, it seems a safe bet that B. will have one or two things to say about the oeuvre of one Charlie Kaufman. You’d be right in thinking that all this is starting to sound

META-META

Sure to be dabbed off your bingo ticket in a heartbeat, as Kaufman breaks not just the fourth wall, but the fifth, the sixth, the seventh. Antkind is a work about a work, in that its plot revolves around an unseen 3-month long film, which took its auteur 90 years to complete. Only problem is, the film is destroyed. All that’s left is a single frame, and B.’s mission is to restore it, since he believes humanity desperately needs this

MAGNUM OPUS

From Caden Cotard’s epic piece of theatre – a simulacrum of daily life – to Craig’s marionette performances in Being John Malkovich, Kaufman’s work is filled with creatives striving to push boundaries. Each expresses anxiety over ‘labour, time and value’; it’s a thin line between greatness and gimmickry, especially when the work involves

PUPPETS

What’s more gimmicky than a puppet? So much labour goes into making them look realistic, and yet they always look (charmingly, disappointingly?) stilted. As well as Being John Malkovich (and casual mention of a ‘puppet theatre’ in Adaptation’s penultimate scene) puppet-like stop-motion is used throughout Anomalisa.

Kaufman’s work is fascinated with slippery scales and with who’s pulling the strings; with determinism, and Pinocchioid anxiety (I want to be a ‘real man’.) let’s see whether Antkind throws any literal puppets in; but for now, it’s there in the title: are we merely ants to be toyed with by larger forces? Are any of us special, or are we like

THE BLANK

Everywhere in Kaufman, characters are doubled. People become one another. The central gimmick of Anomalisa is not just that everyone is a puppet, but that, to its anhedonic antihero, Michael, everyone speaks with exactly the same voice and wears the exact same face.

Through its very gimmickiness it expresses Michael’s experience of a gimmicky reality: glossed with the possibile sheen of excitement, nevertheless unfailing in letting you down. But don’t worry, I won’t leave you with a

DOWNER ENDING

Kaufman’s films about sad, lonely, fearful men tend to push their recursive form to the extreme and can sometimes be said to dissolve into self-reflexive thought-loops rather than end.

But, in their rehearsal of life’s excitements and disappointments, by pushing the gimmick as far as it will go, pressure breaks in the viewer or reader. Here, self-loathing is pushed to the point of self-erasure, until it bleeds into its opposite – something like self-discovery.

There’s a strain of idealism at the heart of any cynicism, a touch of excitement in every gimmick, and a grain of truth to even the darkest of jokes. As Caden Cotard says, ‘We’re all hurtling towards death, yet here we are for the moment alive.’ Bingo!