★★★★☆

From despair to desire, introspective gloom to dazzling light, this exhibition has it all.

In a dramatic self-portrait, Edvard Munch (1863-1944) stares out at us, looking both grand and cautious. Self-Portrait in the Clinic (1909) was painted while the painter was in a clinic, as he was treated for a nervous breakdown. After years of working strain, public derision, disastrous affairs and heavy drinking, Munch had hallucinations and collapsed. He committed himself to a Danish clinic, where he was one of the first patients to receive electro-convulsive therapy.

The current exhibition Edvard Munch: Masterpieces from Bergen at the Courtauld Institute, London (27th May–5th September) shows aspects of the Norwegian artist’s turbulent life. The exhibition includes all Munch’s major genres. These paintings are loaned from a museum in Norway, all collected by Rasmus Meyer.

Meyer knew the artist personally and bought pictures directly from his studio. He selected the best paintings, ones that showcased Munch’s core themes and stages of his development. That provides an ideal selection for this small exhibition (only 20 paintings), which distils the essence of the Norwegian genius.

Edvard Munch, 1863-1944, Self-Portrait, 1909 KODE Art Museums, Bergen, Norway.

Edvard Munch, (1863-1944), Morning, 1884, KODE Art Museums, Bergen, Norway.

The earliest painting in the exhibition is of a woman (probably a servant) dressing in the morning. The canvas, painted when the artist was 20, met a controversial reception when exhibited at the annual salon in Kristiania (now Oslo). In it, the commitment to realism in the subject and Modernism in the rough style set out the young painter’s commitment to the avant-garde. Women – clothed and nude – would become the main protagonists in Munch’s paintings.

Two views of the main boulevard of Kristiania, painted two years apart, exemplify Munch’s rapid development. The 1890 picture shows the sunlit street in summer, painted in a lively Impressionism manner; the 1892 picture is an Expressionist painting of the street in winter, the staring faces on the night street burning their icy presences into the consciousness of the painter. Day has become night, light has become dark, dainty has become direct, dappled glints have become suffused soakings.

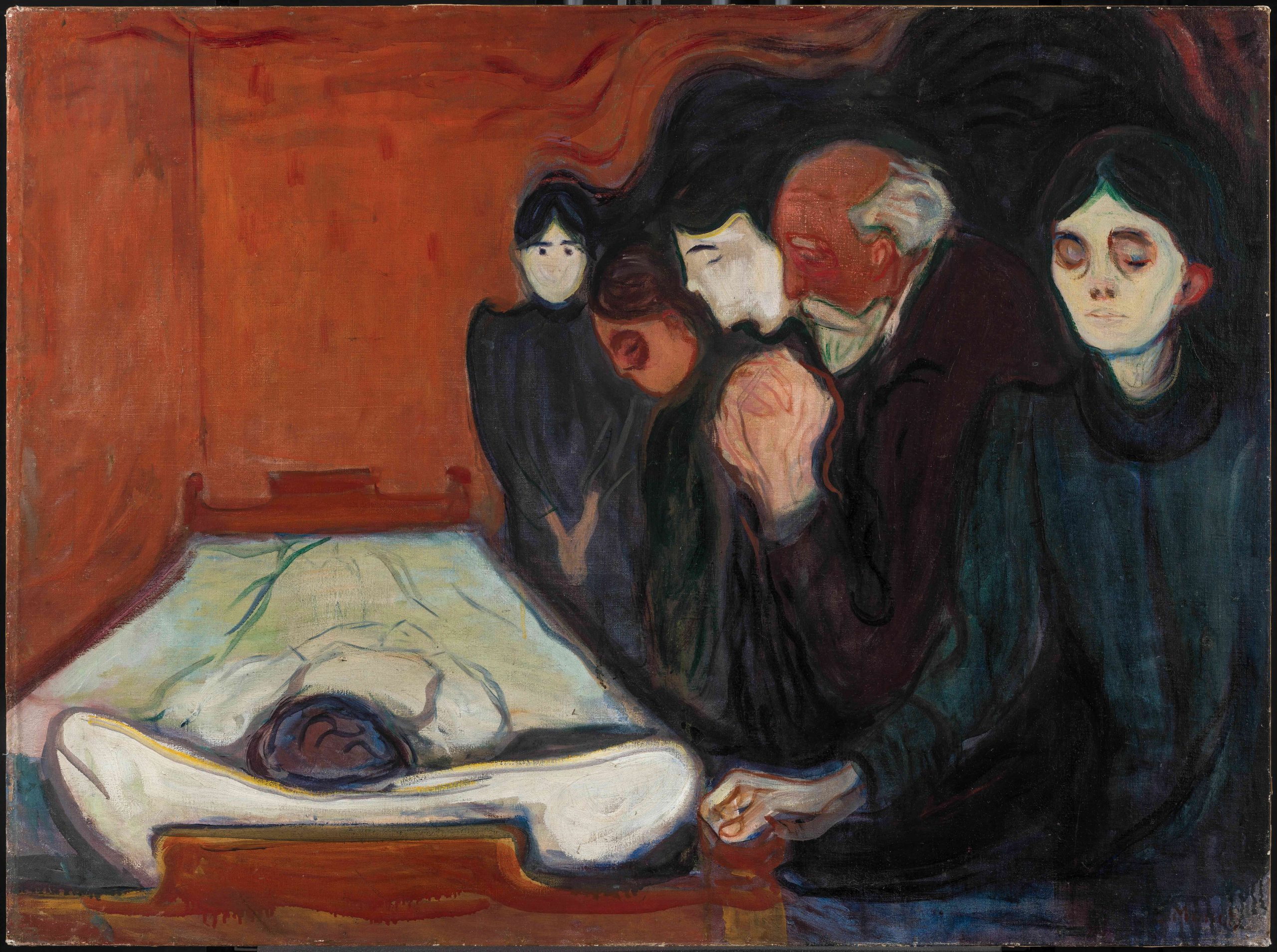

At the Deathbed (1895) shows the grieving family members at the deathbed of a relative. Munch’s mother died of tuberculosis when the future-painter was five years old. He thought that his family was cursed, hardly surprising when his sister also died of the same disease. Tuberculosis was rampant in Norway, at the time a desperately poor rural country. Depression and anxiety stalked his family and Munch himself went through bouts of depression and paranoia.

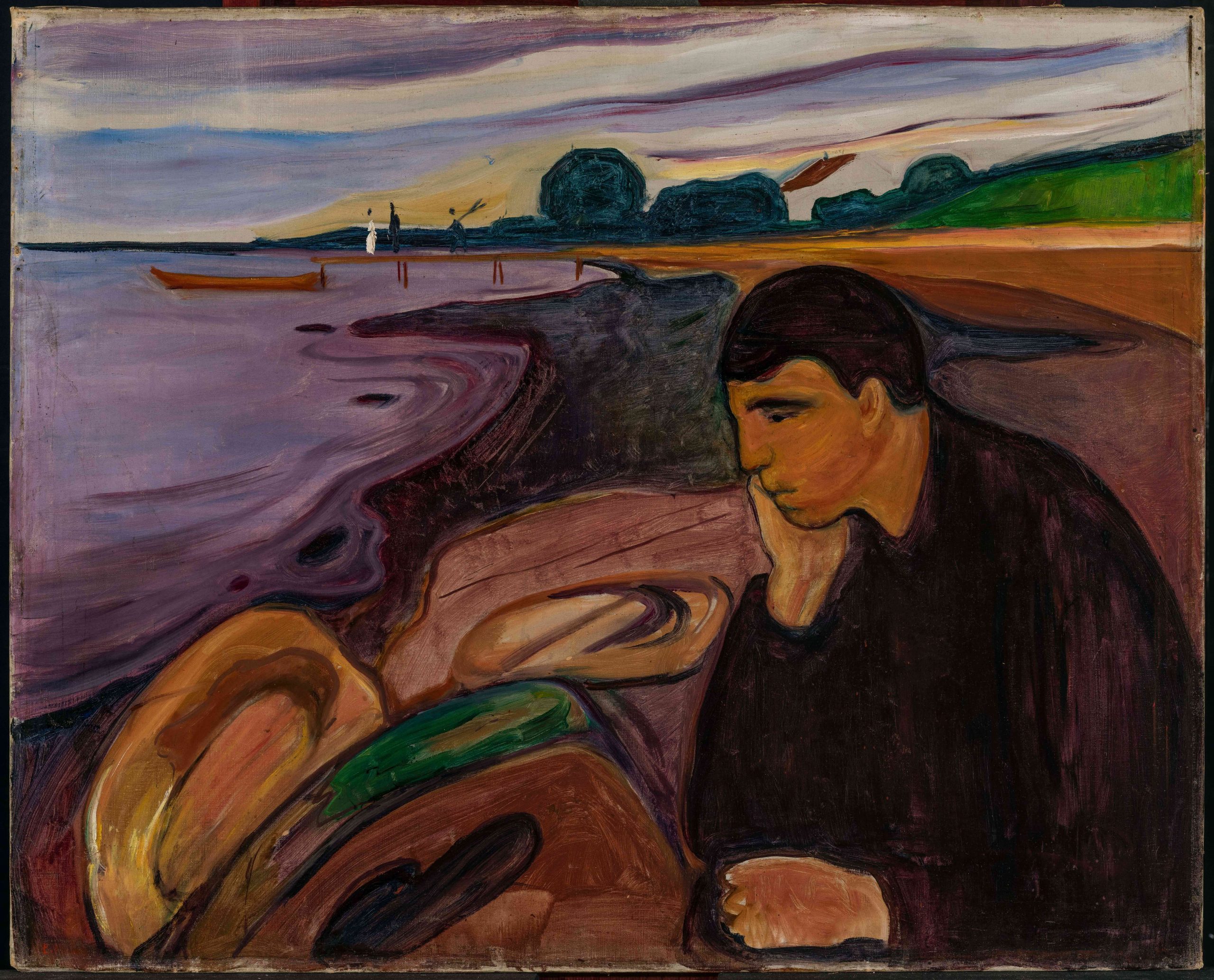

Melancholy (1894-6) shows a lone man on a beach suffused with introspective gloom. The unnaturally intense colours reflect the man’s strong emotions. A different kind of alienation is present in a painting of children on the street. The children seem strange, reserved, even malevolent, like a scene from a horror movie. The painting is set in the small town on the Norwegian coast that Munch lived in.

Edvard Munch, (1863-1944), At the Deathbed, 1895, KODE Art Museums, Bergen, Norway.

Edvard Munch, (1863-1944), Evening on Karl Johan, 1892, KODE Art Museums, Bergen, Norway.

In his Berlin period 1892-6, Munch’s brilliance attracted devoted followers and contemptuous critics. His personal intensity and heavy drinking in Berlin’s bohemian bars stimulated his creativity. Association with leading writers, including August Strindberg, led to Munch coming to see the vital cause of art as delving into eternal matters: desire, hatred, jealousy, death, despair.

He conceived of a series of paintings he called The Frieze of Life, in which he would tackle these themes. In the majestic Woman in Three Stages (1894), we see on a seashore a woman in three stages: childhood, youth and maturity. They are accompanied by a downcast man, almost hidden in shadow.

The artist has been accused of misogyny and it is easy to see why Munch (who never married) had a cynical view of relationships. He had a knack for choosing unsuitable women; an eventful love life, with many relationships, including one which resulted him being shot by his lover. Although Munch undoubtedly suffered, the resultant dramatic images and moods account for his popularity.

There is an early painting of his sister Inger on the seashore. There are scenes of men and boys, nude bathing on the Norwegian coast. These dazzling paintings show Munch’s embracing of the cult of naturism, then very popular in Germany. Munch, a handsome man, had himself photographed nude while painting on the beach. He painted outside sometimes and had the eccentric habit of putting new paintings outside “to weather”, hence the weather-beaten surfaces and watermarks on his paintings.

Although compact, this exhibition is a brilliant summary of Munch’s art. An absolute must-see.