As you enter, you feel you’ve crossed the threshold of a dream: people glide in and out of cavernous rooms and the noise of the square outside is replaced by a sacred silence usually reserved for holy places.

Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, 1610

Along the walls, people stand in private communion with the paintings. The quiet punctuated by the sound of heels on wood-panelled floors. At least it’s quiet till someone coughs – a sound that erupts like a sneezing panda – sending people scattering as if from a radioactive forcefield.

At times you have eye contact with passersby (every Londoner’s nightmare) and realise there’s an unspoken affinity between all these strangers, each with their own reasons for ending up in the National Gallery on lockdown eve, united by your desire to see art and feel a closeness with the old Masters (before the chrome vault doors once more slide shut).

Yet apart from the odd side glance, nobody pays attention to each other; the paintings have a much more commanding presence. Figures glower down from their celestial heights, almost mocking, safe in the peripheries of their frames. Faces run the gamut of human emotions: from sullen and weeping to composed and deep in thought, to full-on fury emitting lightning bolts of rage.

Canestra di Frutta, an early Caravaggio from 1599, aged 17

You’ve dragged a friend along with you, who once studied art history and acts as your de facto guide. He thinks he remembers where the Caravaggios are, but the rooms seem to multiply beyond reach and the guards stationed at each entrance eye you with undisguised suspicion. Lost in the one-way system with multiple obstacles and masked adversaries, it suddenly feels like you’re trapped in a video game.

But then you see them…

Side by side on the opposite wall, left to right: Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1593–1594), Supper at Emmaus (1601) and Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (1607) – one painting from each of the distinct phases of his career. Neither are of the grand proportions you were expecting, but it doesn’t matter anymore. Here you are in front of not one but three Caravaggios, in all their dark, brilliant glory.

Supper at Emmaus, 1602

Caravaggio is known as many things: a great Italian painter – also a murderer, slave holder and notorious criminal. Born as Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio in 1571, his early life was shadowed by the plague that swept through Milan, killing most of his family.

At 21 he moved to Rome, Italy’s artistic centre. But arriving destitute, the first few years were tough. He specialised in still lifes of flowers and fruit and later, half-length figures (like Boy Bitten by a Lizard), which he sold on the street. The year 1600 was a turning point for Caravaggio as his talent was recognised by eminent collectors, including Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte who took him into his home.

After receiving a major commission for Rome’s Contarelli Chapel, Caravaggio’s fame and reputation were catapulted beyond the confines of Rome. Yet his reckless behaviour was proving a problem. It was said he used to go out with a sword at his side “like a professional swordsman, seeming to do anything but paint.”

Boy Bitten by a Lizard, 1593

In 1606, Caravaggio got into a fight which turned fatal when he plunged his sword into his rival Ranuccio Tomassoni, hitting his femoral artery. He immediately fled, becoming a fugitive overnight. Caravaggio was sentenced to death for murder and an open bounty was placed on Caravaggio’s head which meant that anyone who recognised him could legally execute the sentence.

Around this time, severed heads began to appear frequently in his work – sometimes depicting his own head on a platter – suggestive of the deep unease he must’ve felt. Salome Receives the Head of John the Baptist (1607) is one example, which illustrates the Gospel story of how when Herod asked what she wished for, Salome replied she wanted the head of John the Baptist.

Outlawed, Caravaggio went to Naples, then Malta (which was ruled by the Knights of Malta, an ancient religious order) in an attempt to become a Knight himself, hoping that this esteemed position would help secure a pardon for the murder. He was granted the knighthood and as a reward, Caravaggio was presented with two slaves and a gold chain. However, his status was short-lived as he got into a fight with another knight and was imprisoned. But – (classic Caravaggio) he escaped.

The Cardsharps, c. 1594

Like a vagabond, he travelled around Sicily and Naples continuing to paint, while another brawl left his face severely disfigured. After finally getting a pardon from the Pope, Caravaggio was set on returning to Rome. He loaded his belongings onto a ship but, for some unknown reason, was arrested and had to buy his way out of jail. By the time he was released, the ship and all his possessions had left the port. As he made his way along the coast he fell ill, and days later, just 39 years old – alone and feverish – he died.

–

Tempestuous, violent and impulsive, Caravaggio’s life was as dramatic as his paintings. Although he was loathed by many, he was revered for his daring, unconventional approach to painting and unflinching realism.

Caravaggio’s art centres on biblical themes, yet he defied the aesthetic conventions of the time and focused on ordinary people and settings, depicting a kind of ‘everyday miraculous’ (fiercely denounced by critics as “sacrilege, vulgar, and disgusting”). In Supper at Emmaus, painted at the height of his career in 1601, a resurrected Christ appears before two of his disciples over a meal. For this painting, Caravaggio has chosen to show the apex of a familiar narrative from the Gospel of St. Luke: the moment Christ blesses the bread and the disciples realise the true identity of their fellow diner.

And when he had sat down with them at the table, he took bread and said blessing; he broke the bread, and offered it to them. Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him; and he vanished from their sight. (Luke 24,13-35)

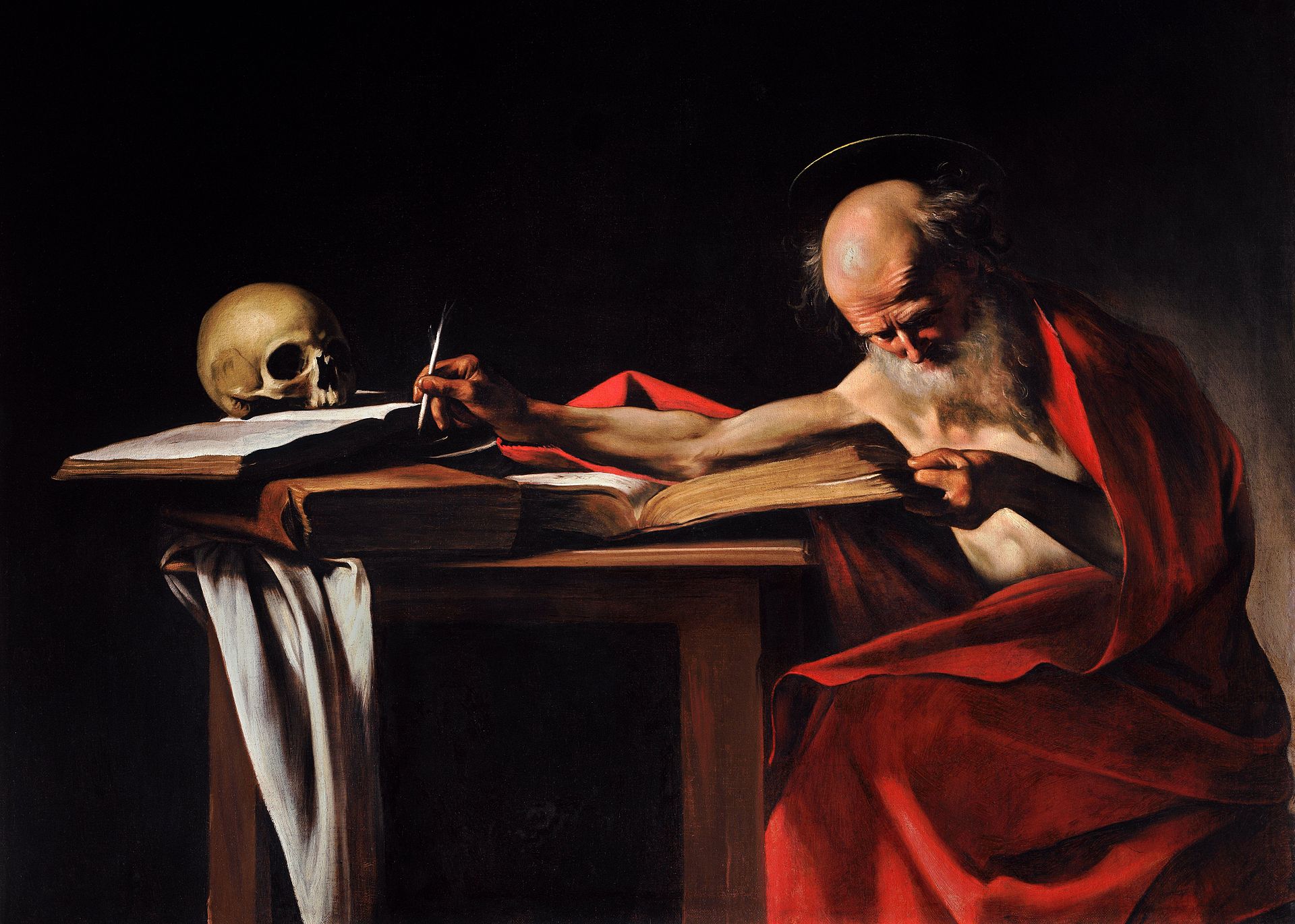

Saint Jerome Writing, c. 1605–06

Look closer, and sudden details come to light: the torn fabric in the elbow of the man’s jacket, the intricate contours of the scallop shell attached to the disciple’s chest (the shell itself emblematic of pilgrims), the fruit basket precariously balanced on the table edge, the apple starting to rot (the Fall of Man). Through all these elements, we understand that nothing is accidental in the picture, everything is placed there for a reason, each object imbued with its own symbolic purpose.

Masterfully, Caravaggio makes us feel part of the scene, with the cropped composition bringing the viewer right into the picture space. The two disciples seem to break through the canvas, while Christ’s grounded presence has a magnetising force, made all the more powerful by the shadow behind him.

Portrayed in this ordinary setting, he makes these biblical figures – long gone and distant – close and familiar. Discussing his work, the 17th century writer Giovanni Pietro Bellori noted the intimacy of Caravaggio’s scenes: “[he] never brought his figures out into the daylight but placed them in the dark brown atmosphere of a closed room, using a high light that descended vertically over the principal parts of the bodies, while leaving the remainder in shadow, in order to give force through a strong contrast of light and dark.”

The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1600, a perfect example of Caravaggio’s mastery of chiaroscuro

Of course, it’s impossible to speak of Caravaggio without speaking of light. Though he’s often associated with candlelight, not a single candle appears in any of his works. A wizard of chiaroscuro (literally ‘light-dark’), Caravaggio demonstrates the symbiotic relationship between both elements. The expressions and gestures of the two disciples are illuminated and engaged, while the innkeeper above Christ’s shoulder seems not to have recognised him (yet), and his face remains half in the gloom. Caravaggio doesn’t just use light for aesthetic effect, but to underpin the meaning of his pictures. Here, it’s the light of revelation.

–

I’m sure I’m not alone in my urge to see these paintings in these extra uncertain days. Indeed, many artists have been looking back towards their predecessors and restyling and recontextualising iconic works of art.

Earlier this year, the street artist Lionel Stanthorpe spray-painted a coronavirus age version of Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus in Ladywell, southeast London, bearing one key alteration – Jesus is wearing surgical gloves. Elsewhere, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa has been revisited in countless ways, including images of her self-isolating in the Louvre Museum, or covering her face with a surgical mask.

Judith Beheading Holofernes, c. 1598–1599 or 1602

Like photography, an old painting allows us to step into another time, opening a channel of communication between you / the artist. Yet within the painting, no matter how ancient, there exists a recognisable humanity, something essential which binds all of us together. Through Caravaggio, we encounter the darker aspects of humanity: the pain, vulnerability and unpleasantness. Neither does he shy away from death. That’s not to say his paintings are depressing (though some will disagree).

Instead there’s a beauty to be found in the darkness of Caravaggio’s scenes, a sense that in life – just like chiaroscuro – the darkness is needed to fully appreciate the light.