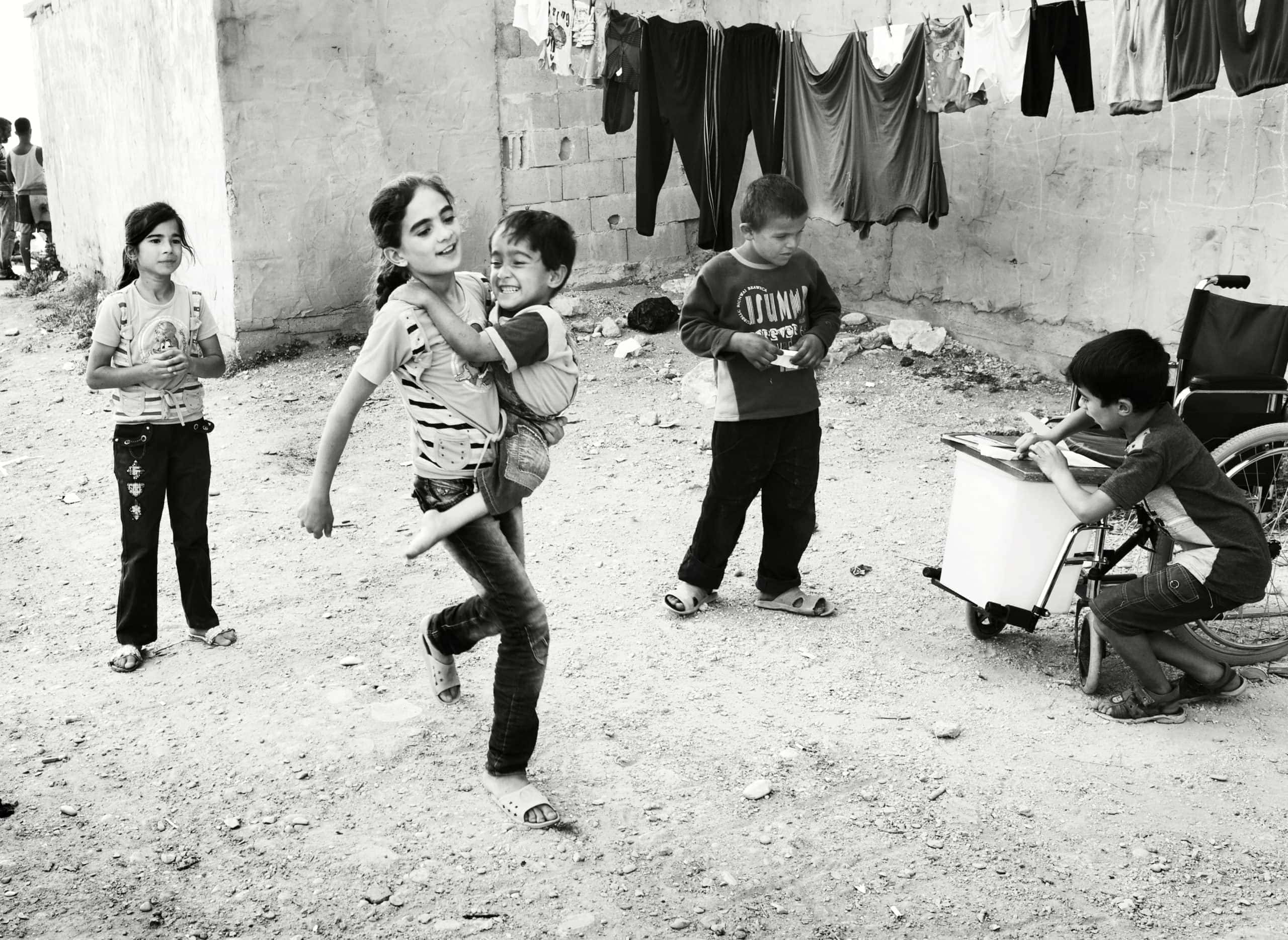

The family of Prymorska Street. / Andrei, Colya, Ruslana, Sasha, Lydia, Dima, Nadya and Lilick

At his Hastings apartment, Giles Duley attends to the shrill beeping of a timer. He’s cooking pork belly – something he’s learned to do since his 25 years of vegetarianism came to an abrupt end following a horrific accident. Over Skype, he tells me how his sister visited him in hospital, asking what he wanted to eat and he had a sudden, intense craving for a steak.

Giles is a storyteller, whose fascination with people led him naturally into photography. Starting out as a music photographer, he was immersed in the rock‘n’roll scene at the peak of the Britpop era, travelling with bands like Oasis, Blur and The Prodigy. But later, he swapped the glamour of the celebrity world and started photographing the unheard stories of the lost and marginalised in some of the most challenging places on earth.

In 2011, Giles was working in Afghanistan when he stepped on a landmine, losing both legs and his left arm in the blast. Now a triple amputee, he describes emerging from the experience a better man. Just one year after his accident, Giles returned to work with a renewed sense of purpose. In 2017, he founded the Legacy of War Foundation to support those affected by conflict and as well as a photographer, he’s a humanitarian activist and writer. In his spare time, he runs an Instagram page called The One Armed Chef, sharing dishes he makes in his kitchen.

In the midst of this global pandemic, we speak to Giles about his career, what he’s learnt along the way and what advice he has for dealing with isolation, change and uncertainty.

How did you first get into photography, Giles?

I was 18 when I was given a camera. When I was younger, I was always a problem child. I did sport mainly, I wasn’t very academic. I was dyslexic, everyone thought I was stupid and I was moved back a year. School was hell for me. Everyone says they’re the best years of your life, and I hated every minute of it so when I left school I went to the States to pursue a sporting career.

I had a car accident though, and although it wasn’t that big, it was enough to damage my knee so I couldn’t do sport anymore. I came back to the UK and was a really angry, frustrated teenager that just didn’t know what he was going to do with his life and that was when I got given a camera.

I think of it as being given a voice for the first time, because being dyslexic and being held back a year at school dents your self-confidence so I couldn’t really communicate with the world. As soon as I had a camera I felt like I could.

I never planned to become a rock‘n’roll photographer, but when you’re 19-years-old and you’re suddenly on the road with bands like Oasis, you kind of go: “yeah, I’ll do this for a job!” I did that for ten years and it was great. I got into fashion as well and had some amazing experiences, but over a period of time the whole facade of it started to fade.

I was 18 when I was given a camera. I think of it as being given a voice for the first time… As soon as I had a camera I felt like I could communicate with the world

Is that when your interest turned to humanitarian issues?

It’s not like there was one moment. I love portraits – I’m a portrait photographer. Even though I was photographing fashion, music and conflict, it was all about people. I’m fascinated by people and the camera’s an amazing tool. A great portrait is a really intimate moment with someone. It’s like being on a date; that moment when everything in the room just disappears and it’s just you and that person – that for me is photography.

I was in my late 20s and I became more interested in politics and what was happening in the world. I just didn’t fit the world of fashion and celebrity culture, so I gave it up one day. I threw my cameras out the window in the middle of a shoot. I had a big hissy fit because there was an argument involving a young actress, who was in tears because this client was telling her she had to be semi-naked on a bed and she didn’t wanna do it – even her own agent was telling her she should. I thought: “f**k this, this is not what I got into photography for.”

The story is that I threw all my cameras out the window, but I threw them on the bed. It was a bouncy bed though, so they bounced off. For years you could still find the crack in the pavement on Charlotte Street where the cameras smashed.

After that, I moved down to Hastings, got a job in a bar, had no idea what I was gonna do with my life, and sank into a very deep depression. I was drinking all the time, getting wasted and was just completely lost. I was married too, and that ended. I couldn’t really see much purpose in life. It was a bit like I said: when I was given a camera at 18 I got given my voice; when I gave up photography, I lost my voice.

If you’re doing something for somebody else it makes you get up in the morning

When I was really, really low, I got a job as a support worker for a young man with autism, called Nick, and I became his live-in carer. It was supposed to be one day a week and it ended up being seven days a week and I did that for 2 years.

What was that like? Was he your age at the time?

He must’ve been about 19-20. I was about 30. It was intense, although I think when you get really depressed, you stop caring about yourself, but if you’re doing something for somebody else it makes you get up in the morning. There were days when I didn’t want to get out of bed and I had a responsibility for somebody, so that gave me a sense of purpose even though I had none. I did that for a couple of years and at the end of that I started taking photographs again, started documenting his life to try and help him tell his story.

First Day of School, Angola. 2008

That’s when it all made sense that actually I could use photography to help other people to tell their stories. There’s a phrase that gets used a lot: ‘to give people a voice’. It’s a stupid phrase because people have voices. I don’t give them a voice, but I make sure their voices are heard. The camera is this amazing tool for magnifying, amplifying people’s voices, and that’s what I realised with Nick – that’s what I could do with him and that’s what I should do really with my life, so that was the transition to doing humanitarian work and covering conflicts.

So then you went to Afghanistan for the first time, what year was that?

2011. I started doing humanitarian work in 2006 in places like Angola, DR Congo, South Sudan and Bangladesh. Then after five years, I was in Afghanistan doing that kind of work when I had a bad day at the office.

‘To give people a voice’ is a stupid phrase – I don’t give them a voice, but I make sure their voices are heard

In those five years before the accident, did that kind of work feel closer to what you wanted to do?

It was everything to me.

Where exactly were you when you had your accident?

In Kandahar. ‘The Heart of Darkness’, they call it. It was the worst place in Afghanistan at the time. It was the village of Mullar Omar, who was the founder of the Taliban. There was a lot of combat fighting. I often get called a war photographer, but I’m not that at all because I don’t photograph people firing guns. There’s not a single picture anywhere in my work of a soldier, a gun or a tank. I don’t think you can ever take those pictures and not glorify war in some way; it’s a weird paradox.

So you focus more on the aftermath, the communities, recovery…

Exactly – the reality of it. The reality is a really ugly thing.

Can you talk about how you got injured and what happened afterwards?

The accident itself is almost imprinted in my memory. It was a normal day out on patrol with some American soldiers. I wasn’t photographing them, but the impact that war was having on those soldiers. And we got ambushed. It was an area where there’s constant stuff going on. I went running for cover and I stepped on an IED – a landmine that’s triggered by pressure.

I thought they were the last moments of my life, lying in the middle of a muddy field in Afghanistan

It’s impossible to explain, other than I would say a deep sense of feeling very alone and I thought they were the last moments of my life, lying in the middle of a muddy field in Afghanistan. But then [the medics] reach me after what seems like an eternity, and they put the tourniquets on to stop the bleeding – painful as hell…

You were still conscious at that point?

I never lost consciousness. It was like a scene from Apocalypse Now, because the helicopters that came to rescue me were coming down the valley, firing off flares and a seargant called Chris Max had lit a cigarette and was helping me smoke it, because my remaining hand was mangled, I couldn’t move it. If I’d seen it in a film, I would haven said: “that would never happen!”

ArraySo I’m lying there, having this cigarette, having had my legs blown off, and there are helicopters flying in to pick me up; it was a very surreal moment. And then we had a 25-minute helicopter journey back to the main base in Kandahar – that’s when I lost consciousness.

So you were in hospital, in isolation for a month – you couldn’t eat, move or talk, you weren’t sure if you were going to live or die. What was going through your mind?

I was in the extreme of isolation. People are in isolation now, and obviously it’s challenging in lots of different ways. I was in the deepest isolation you can be. I am strapped to the bed. I can’t move. I can’t speak because I’ve got tubes in my throat. So the only way I could communicate with the world – the only connection between me and the world – was through blinking. Try lying down for half an hour in your bed, staring at the same bit of ceiling and not moving. Imagine being unable to move, not being able to communicate apart from blinking and do that for about 1,000 hours – that’s what I did.

Imagine being unable to move, not being able to communicate apart from blinking and do that for about 1,000 hours – that’s what I did

In intensive care there are people running around all the time, and if you get sucked into that world, you go into panic mode. I didn’t really know how badly injured I was. Every so often they’d hold up an alphabet so I could try and blink when they stopped at a letter, but it never really worked. I couldn’t communicate, so I was in my own mind. At first, it was a panic state. Chaos. I’d describe it like jumping in the freezing cold water, where your breath goes and you just can’t do anything. Then I realised, “shit, this is going to go on for a while. I’m stuck here and I’m gonna go mad if I don’t control this.”

So I started to build a world in my mind to control it. I had no idea of time, I didn’t know how many days I’d been there, if it had been weeks, months. As I said, there are no clocks in intensive care. The light’s always on, so you can’t tell what time of day it is. But what I realised was that the nurses would come at regular intervals to take my blood pressure, check all my vital signs.

So I decided that would become my unit of time: every time they came would be a unit. To this day, I’ve no idea whether it was 20 minutes or 2 hours. But I just know that was my one unit of time, and I began to use those units of time to visualise projects.

I had one project that was called ‘100 Portraits Before I Die’, where I thought of 100 people I wished I’d done portraits of. I wouldn’t just make a list and imagine these people, but in one of these units of time I would imagine the whole photoshoot: I imagined turning up, meeting them, what I would say, what they’d be wearing, what I’d be wearing, where we would be, what the weather was like, I would imagine walking to the studio, how I’d set up the lights, whether it would be outdoors, what camera I was using, I would do everything. I had every detail of that shoot in my head – and I did the 100 portraits.

You realise that one thing that nobody can take away from you is your imagination – no matter what happens, no matter where you are, you can create a universe in your mind

What was the purpose of those projects?

I did those things to keep myself sane. As I said, you can’t be more isolated than that, because any more isolated than that you’re dead. But you realise that one thing that nobody can take away from you is your imagination. And no matter what happens, no matter where you are, you can create a universe in your mind. And you can create a world for yourself.

The other thing I’d say about isolation is that you can’t control what’s happening around you. Most people I know are in a state of anxiety and chaos because of everything that’s happening around them; they say they’re having weird dreams and they’re not sleeping well and that’s because your mind is outside the house and worrying about these things we have no control over.

Nearly all of the Nguyen family have been affected by the toxic legacy of Agent Orange, which was sprayed by US forces during the Vietnam War as a defoliant.

Of course you should be aware of what’s going on, but focus on the things you can control. I didn’t know how long I was going to be in hospital, if they were going to cut more bits off me; I didn’t have control over anything, but I could control what was going on in my mind.

We can’t control how long this lockdown goes on or how long the virus is impacting our lives, but we can control who we’ll be as it happens. And we can control who we’ll be at the end of this lockdown. So my mindset again now is, “okay, how can I be in a better position, how can I be more focused when this is over? What can I learn?”

We can’t control how long this lockdown goes on or how long the virus is impacting our lives, but we can control who we’ll be as it happens

That’s not to say you have to be doing amazing things every day. I still spend most of the morning watching episodes of Frazier in my underwear. But you should be able to allow yourself days of grief and feeling overwhelmed. When I was in hospital, I had days where I was just overwhelmed. I’d lost my legs, my arms, my home, everything – and I’d be in tears most of the day, but I’d sort of allow it, I wouldn’t beat myself up. I’d say: “okay today, we’re just gonna have a crap day, feel s**t it’s fine.”

That element of control is one of the things that everyone feels they’ve lost in a crisis like this. But you can even control the days when you feel s**t because you let yourself do that, rather than go, “Oh God, pull yourself together! Do 20 minutes yoga, 20 minutes this, 20 mins that.” No. Allow yourself to feel s**t. Then the next day you can say: “Okay, yesterday I felt shit, today I’m gonna do some stuff.” It’s about balance.

Orphanage, Angola. 2008.

Do you think there are any positives we can take away from this current situation?

As a creative person, it’s a great time to experiment. Most creatives have pressures because when they’re on assignment or when they’re doing a brief they have to stick to what that is. Now’s a time when you can try out different things. It’s a great time to build new collaborations and new contacts.

I’ve been speaking to people that I’ve been trying to get in contact with for years, and been having some really interesting conversations. I’m already excited for when lockdown finishes because there are some new things happening now that weren’t happening before – and that’s a real positive.

Going through a life-changing injury is not easy to deal with – I still came out of it a better man, a better person, a better artist

I remember three months after I got injured, I went through probably one of the worst times, in coming to terms with the grief of what had happened. I was about to have a shower; it was the first time I’d seen myself and my injuries in the mirror for three months and I was almost repulsed, disgusted and didn’t recognise myself. It was a real slap in the face of the reality of what was going on.

I went to bed and I just cried myself to sleep and thought, “I don’t wanna live, I don’t wanna be this person. I’m not strong enough.” The next morning I woke up and said, “you know what, I will never think about the things that I can’t do. I will focus on what I can and I will excel at those things.” And I can honestly say that going through a life-changing injury, it’s not easy to deal with what happened. I still came out of it a better man, a better person, a better artist.

ArraySince your injury, cooking has had a large role in your life and it’s interesting to see people turning to cooking and baking now during lockdown. Was that an interest before your accident, or did it come after? And what benefits do you think cooking has?

My mum’s a really good cook. When she was a teenager she was sent off to some stately home during the war to work as a servant, so I had this background of cooking, but I’ve never actually cooked with my mother. It was more I just enjoyed it. Then when I got injured, it was then part of coming to terms with what had happened. I didn’t like people constantly saying, “I’ll do this for you.”

I was in a very dark place. I shut the curtains and didn’t want to speak to anyone. But then I started cooking

You’d order something at a restaurant and it would come out already cut up without me asking, and it pissed me off because I’m like, “I can do everything it’s just that your assumption is that I can’t.” So it all started as a joke to prove to people that I could still do stuff.

But also, it became really important to me about four years ago when I returned from Mosul [in northern Iraq]. It was probably the worst thing I’d seen in terms of children injured and really horribly maimed people. It was a difficult time and when I came back, I was in a very dark place. I shut the curtains and didn’t want to speak to anyone. But then I started cooking.

Former rebel soldiers, Angola. 2008

Normally, if I come back from a difficult trip and read a book or watch TV, my mind is still racing – I can’t really switch off. With cooking, it’s a bit like running, or what I imagine happens when you meditate, because you’re stuck in the process – you’re making something like bread or pasta, your mind is stuck in that manual task and you forget about everything else.

For a week, the people in my building loved me because I was cooking through the night as I couldn’t sleep. I was in a dark place, but I kept just cooking. I’d leave stuff outside their doors because I had more food than I could possibly eat; it was my therapy really, a way to escape from the nightmares of work.

With cooking, it’s a bit like running, or what I imagine happens when you meditate – your mind is stuck in the manual task and you forget about everything else

On the flip side of it, I also use it as a way to build relationships with people I photograph. I always say I’ll make a better portrait if I’ve eaten with the person first, because to me, the difference between an acquaintance and a friend is when you eat together. Once you eat with me, you’re my friend. It’s as simple as that.

How else are you staying motivated at the moment?

It’s hard. There are always days when you feel despondent. There were a lot of long-term projects I’ve been working on that have disappeared now, and they probably won’t come back. It’s easy to get lost in grief, but I’m also very aware that things pass and change.

Murle women in Lekwongole.

One of the interesting things about people is that our greatest growth comes through change. The weird paradox of that is people don’t like change. We don’t like to create change. And probably the worst position is when lives are okay, because we don’t like to upset the balance.

So things we might do when we were younger – like go to university, or move to London – all those things are difficult changes, they’re challenges at the time, but they’re the things that make us stronger.

Our greatest growth comes through change. The weird paradox of that is people don’t like change… but they’re the things that make us stronger

What’s happening now, individually and collectively, are massive changes and that will create growth. That will happen for everybody, and something new will come out of it. I think that will happen in society as well.

A lot of people have asked me about resilience. Resilience is a word that gets used a lot, and I hate the word because the thing about resilience is, the more resilient you are means the greater your suffering has been. So whenever I meet anybody that’s resilient, it actually makes me sad because I know they’ve suffered. It’s a quality I don’t want anyone to discover. But I also don’t think you can make yourself resilient.

War Widows, Angola. 2008.

People have said to me, “you’re very resilient for what happened to you. How can I be more resilient to deal with what’s happening?” I don’t think you can actually create resilience. You can’t make resilience. You can’t decide one day, “I’m gonna be more resilient.”

Resilience is the gift that life gives us in return for suffering, so all of us are suffering in different levels through this period and all of us will get that reward of a certain resilience at the end of it.

All of us will come out of this with a certain amount of growth, with a certain amount of extra resilience

We’re in a tough situation – it’s really tough for some. For others, it’s okay. All of us are losing something. All of us will come out of this with a certain amount of growth, with a certain amount of extra resilience.