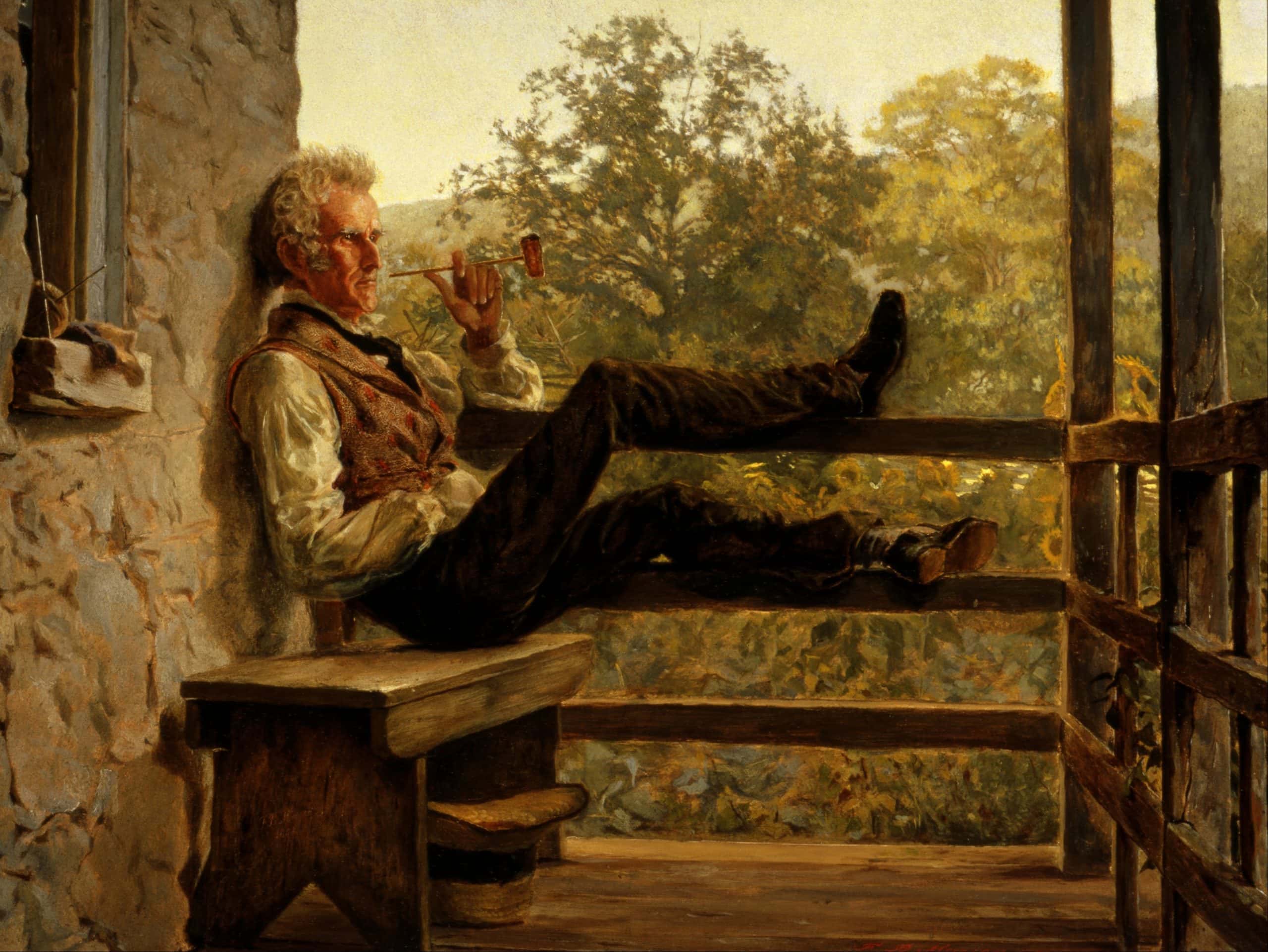

Independence (Squire Jack Porter), Frank Blackwell Mayer, 1858, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C., USA

At the beginning of his novella Transparent Things, Vladimir Nabokov explains the allure of nostalgia: “Perhaps if the future existed, concretely and individually, as something that could be discerned by a better brain, the past would not be so seductive: its demands would be balanced by those of the future. Persons might then straddle the middle stretch of the seesaw when considering this or that object. It might be fun.”

This is classic Nabokov. But it isn’t just his expert distillation of complex emotion into usable shorthand that makes it so, it’s the last four words: a volley of irony that collapses his previous pseudo-philosophical house of cards in a fit of laughter. Nabokov knows all attempts to live without fear of the future, or regret for the past, are doomed to failure—but he gives us the balanced seesaw, so that we can have an amusing image instead.

ArrayMercury and Argus, Jean Lemairec. 1630 – 1635, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, USA

At the start of lockdown, we were made to clamber backwards up our planks to prevent greater tragedy. Suddenly, the diary was completely cleared, and our lives put on hold. We were forced to confront the minutiae of life free from worldly distraction. For some it will have provoked intense anxiety, for others sweet relief. For more still, both. It was dramatic, unsettling, but also novel—we’d never experienced anything like it before.

But the novelty soon wore off. What at first had created a frisson of excitement, quickly became terminally dull. Like most people, I endeavoured to make the most of the pause—to learn a new skill, or augment an old one; to exercise body and mind—while tempering any sense of dread with the belief that it would all be over within months, if not weeks. Spring turned into summer and the desire for immediate release became less acute. Summer is, after all, about a temporary suspension of normal time. The weather was nice, I thought, I might as well enjoy it.

Morning 1926 Dod Procter 1892-1972 Presented by the Daily Mail 1927

Even after it became apparent that there would be no single moment when things returned to normal—no ‘VV day’, if you will—I was still slow to grasp the reality: calendrical annihilation. Plans pushed back from spring, then summer, were abandoned completely. A friend of mine didn’t know, definitively, whether her nine-person wedding would take place until the night before. The only social events capable of planning had to be small mobile affairs that could be moved or nixed at the last moment. There was to be no celebration, not now, and not for a while yet.

One of lockdown’s positive effects was the eradication of the FOMO epidemic. With nothing to feel jealous about we were treated instead to something that might be called ‘JOMO’, aka the Joy of Missing Out. When restrictions were eased, the green-eyed monster returned with a vengeance. I remember being surprised in late summer at how fast cars were driving down my street. Out cycling, I noticed a marked increase in road rage. Then it hit me (not a vehicle, thankfully), people were trying to make up for lost time.

ArrayA Musician,

Albert Joseph Moore, ca. 1867

We’ve been indoctrinated to believe that to succeed in life it is imperative to hit the ground running and not to stop until we’re very old. Since success, in this country at least, and in this city especially, is ineluctably tied to the acquisition of status, we have to get a foot on the ladder quick, or risk falling to our own inconsequentiality—a fate worse than death. The boundaries between work and play have been blurring for years. Having a hobby is good, but far better to have a side-hustle. Or better still, become an ‘influencer’ and monetise your every waking minute.

During this millennium, individualism went into hyperdrive, as did the belief that the only thing stopping you from making a ton of money was yourself. This is a false dichotomy. There are many things stopping each of us from becoming Jeff Bezos, besides the obvious presence of hair. A lot of these are personal, but many more are structural. After the late 20th century mega boom, the early part of the 21st was marked by crisis after crisis. Fragility and corruption became endemic within our economic system. Now, even if you did decide to dedicate your existence to the ruthless pursuit of success, it probably wouldn’t happen. The system is rigged. So, what’s the point?

Young Woman with a Pearl Necklace

Johannes Vermeer, around 1662

Alcoholics Anonymous says you have to hit rock bottom before you know you have a problem. Today, people recognise that the future isn’t looking too concrete, and so are turning back to those things thought alluring in the past. London becoming an emptier place will necessitate some pain, but convulsions are always what have carried humanity forward. When there’s less people here, maybe it’ll become cheaper and, dare I say, more exciting.

While we straddle the rickety seesaw, it’s important not to lean too strongly this way or that. Make vital little plans, ones achievable in no more than a few days. This will keep you moving in the right direction. Until it’s over, be kind to yourself and those around you (at home, on the street, in the train carriage)—this, at least, will be fun.