Iain Andrews in his studio; his work currently hangs in The James Freeman Gallery for the ‘Angels’ exhibition.

The James Freeman Gallery is hosting an exhibition around the interpretation of the ‘angel’. A profound motif in Western Christian tradition, this winged creature of protection and divinity got its archetype from the classical sculpture of Nike of Samothrace, which is currently in the Louvre. The work of seven artists have been gathered to show their own artistic works that have come from the notion of angels – from the feathers to the fallen.

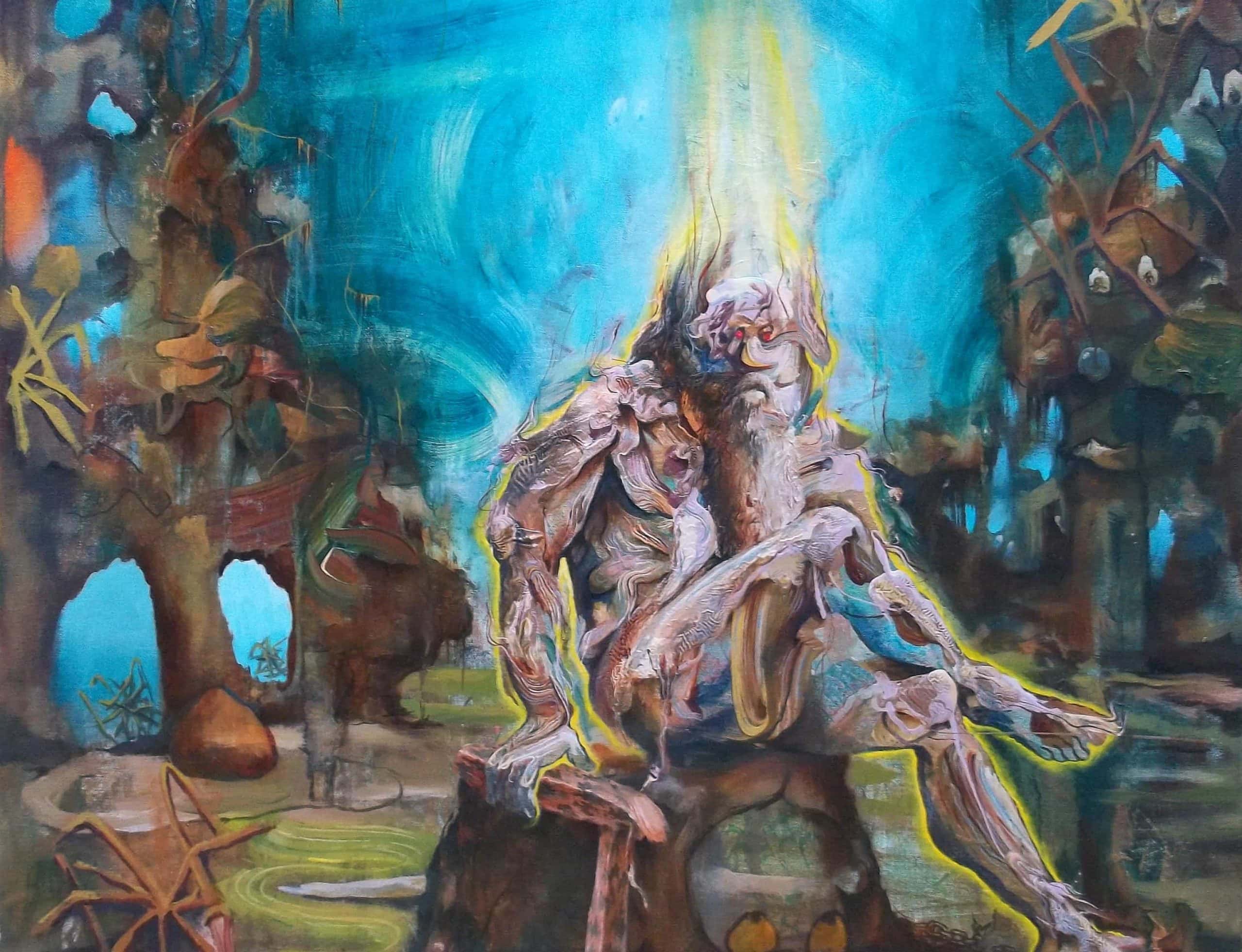

A selection of Andrews’ work is included in the exhibition; his figurative paintings are a constant flesh-coloured morphing of Folk Tale and Faery being retold to learn something new from history. And in the context of this exhibition, they show a historic notion of demonic procession relating to mental illness. Andrews was able to tell me more about his artistic style and how he uses it to express himself.

The work of seven artists have been gathered to show their own artistic works that have come from the notion of angels

How would you describe your style of painting?

I try to balance my paintings somewhere in the space that exists between figuration and abstraction, without them fully belonging to either world. I’m interested in what happens at the edges and perimeters of things. In the moment when a lump of clay hasn’t yet fully taken shape in the hands of the craftsman and yet is also no longer just a lump of material, but sits somewhere between the two places.

Hail Horrors, Hail

Full of potential and yet not becoming, as yet, what it may be. I’ve always found myself something of a square peg in a round hole, and have tended to be drawn to, and interested in, paradoxes and contradictions.

Your work seems less structured than other artists, and rather, more impulsive. Can you talk about how that informs your creative process?

My work will stylistically combine a series of intuitive expressionistic brush marks, which are made very quickly, followed by a much longer, more drawn-out process where each of these marks is finely adjusted using very small brushes. This adds details such as shadows and highlights. When a painting works, it’s not obvious where the impulsive marks end and the tweaking begins.

There are parallels here with my work as an Art Psychotherapist. For the past 18 years, I’ve also worked in Mossside in Manchester with young people with psychological and emotional troubles. As a therapist, there are moments where your training in the framework of psychological theory and knowledge meets your visceral, emotional response to an individual’s trauma or abusive experience.

The ‘Angels’ exhibition runs until the 21st December.

Both the more refined, intellectual knowledge and the intuitive feeling response have an important role to play in how you listen to someone’s story, and in my painting, both the impulsive brushwork and the considered details have their part in the finished whole.

As a therapist, there are moments where your training in the framework of psychological theory and knowledge meets your visceral, emotional response to an individual’s trauma or abusive experience

Can you talk about using paint as a form of expression?

I enjoy the gloopy, synaesthetic qualities of the paint, which feed into ideas of oral greed and deprivation which populate both the faery stories that form the subject matter of much of my work and also the stories of the clients with whom I work in therapy. The physicality of the paint is something I enjoy.

I think most painters get some form of physical satisfaction from messing around with coloured, creamy mixtures – something becomes incarnate there – the spirit becomes flesh.

The Coven

‘The Gerasenes’ seems very reminiscent of William Blake. Is his work something that influences your painting? And what are some of your other influences?

You mentioned Blake as an influence in my work, which he certainly is, much more so in the past than now. The Gerasenes was a region talked about in the gospel of Mark, where a demon-possessed man was healed by Christ, and the demons then fled into a herd of pigs and drowned them.

I wanted to make an image that investigated the moment when man sat on the edge of sanity

I’ve been fascinated by the strangeness of the details in that story and I wanted to make an image that investigated the moment when that man sat on the edge of sanity – the moment when perhaps healing took place but hadn’t yet fully manifest itself.

Other artists who I look at particularly include Soutine, Goya, De Kooning and contemporary painters such as Ken Kiff and Nigel Cooke. The idea of demonic possession and how it relates to mental illness is something that has interested me for a long time and continues to do so.

The Yearning

I think the idea of painting this series of prophets and hermits fits with this idea, as they are traditionally seen as figures who are cast out or remove themselves from mainstream society and as such occupy a unique place from which to listen to the dominant noise.

What message do you hope your paintings convey?

I don’t have a fixed idea of what I want people to read or see in my art. Often people will see an echo or reference to an image from art history, which of course is an intentional device that I employ.

The past repeats itself again and again and reforms and is retold each time and yet I think the essential root or flavour of the remembered experience remains the same. In retelling and representing, hopefully, something useful can be remembered or rediscovered by the viewer.

The Gerasenes

How does your work fit into the exhibition of ‘Angels’?

I guess my work in the show is more about these fallen angels – demons – and how our modern society of concrete, coffee shops and iPhones makes sense of a phenomena that ‘less civilised’ cultures might accept without question.

The past repeats itself again and again and yet the essential root of the remembered experience remains the same.

I think that, as T.S. Eliot says, we’ve lost much wisdom in our quest for knowledge, and replaced much of our knowledge with information, and the casualties of this modern way of being have been our loss of humility and ability to dwell in uncertainty, which has arguably increased our anxiety.

The exhibition at the The James Freeman Gallery explores the motif of the ‘Angel’.

What does being an artist mean to you?

It’s hard to say what being an artist means to me. Working with teenagers is the single best way to expose any of your own conceits or pretensions of what you’d like to be seen as, since they have a way of telling you about yourself that cuts through any self-propaganda you might like to believe.

I think being an artist for me simply means making visual images – trying to find ways of fitting all the unseen, complex thoughts, feelings and responses to the world around me into shapes, colours and lines.

‘Angels’ is open until Saturday 21st December/James Freeman Gallery/354 Upper Street Islington/London/N1 0PD