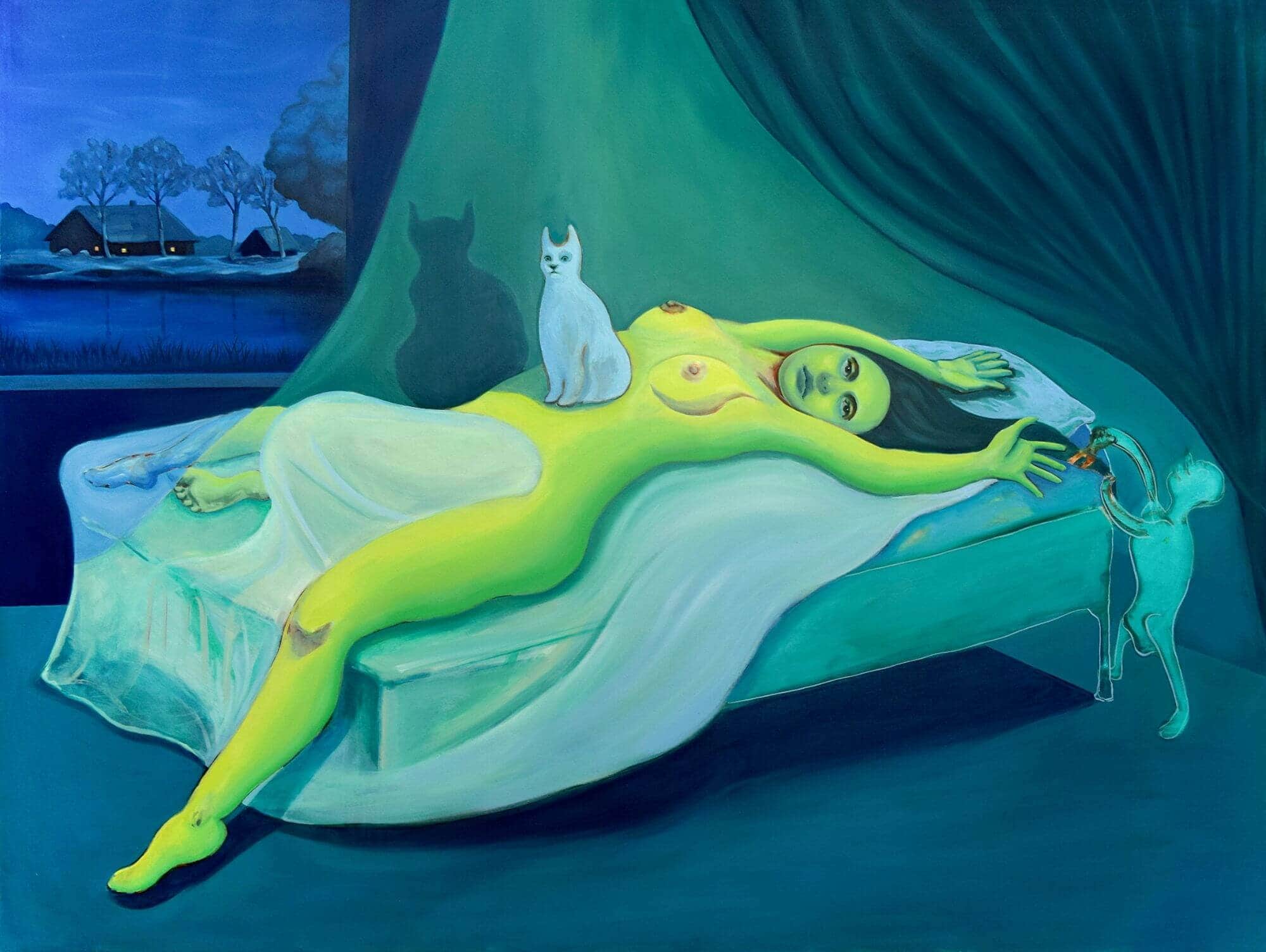

Bambou Gili, Neighborhood Sleep Paralysis, 2020, oil on unstretched linen, 142 x 178 cm

With a scattergun approach befitting its title’s call to action, No Time Like the Present showcases over 50 artists for a digital group show aiming ‘to stimulate connection and engagement in this unprecedented period of isolation.’ Public Gallery’s digital exhibition rallies together over 50 artists to respond to a world in limbo.

ArrayTahnee Lonsdale, Untitled 1 _ 2, 2020, oil on canvas, 26 x 26 cm

It’s tough to be creative at the best of times, let alone under the pressures of lockdown. Luis Mè and Gianna T’s ‘Way to be Loved’ (2020) — which shows a man running at, stabbing, and eventually jumping through a canvas — sums up the frustrations of the creative process pretty well. Yet, as No Time Like the Present proves, artists are adaptable creatures, and improvisation is an art in itself.

A simple conceit, and one that encompasses another old adage — waste not want not — Sally Hackett’s regatta of ‘Garlic Swans’ (2020) are sculpted from a material otherwise headed for the bin. Stems for necks, wispy peel for feathers, crude acrylic beaks — fragile and as regal in as any Life-Hacked bad origami can be — Hackett’s swans embody the Blitz Spirit of the present moment and many more of the exhibition’s themes besides: improvisation, ironic anticlimax, the difficulties of creativity, domesticity, animal companions and food.

William Darrell, Watching the Blossom come and go, 2020, dimensions variable

Sofya Shpurova, Untitled, 2020, oil on canvas, 26 x 31 cm

Sasha Gordon, Flirting with no one, 2020, soft pastel on paper, 61 x 46 cm

Similarly working from what’s to hand — more specifically, what’s in the cupboard — is Lily Wong’s ‘Untitled’ (2020) video work, which begins by zooming in on an egg frying in a pan. The yolk is a shimmering threshold, as sunny side up becomes a sunset blazing over New York. A diary-like montage of life under lockdown follows — a bird bathing in a puddle on a roof, a chihuahua in a tutu glimpsed on the street, a man clapping on his balcony, etc. — before reemerging back through another egg-yolk portal.

Bookended by domestic-fantastic transitions, Wong’s work appears to open a world of dreams, only to collapse it into the everyday. The imagination can only take you so far when it’s not sufficiently fed, or perhaps the fantastic can’t keep up with the unparalleled pressures put on reality.

ArraySarah Thibault, Heating up the sauna (study), 2020, colour pencil on paper, 23 x 31 cm

James Tailor’s ‘Over the Rainbow’ (2020) stages a similar dialogue between reality and fantasy by mashing up clips from The Wizard of Oz with news footage of the NHS. The short film risks being read as overly-sentimental — getting mileage out of the rainbow’s newfound symbolism — yet there’s something unnerving about the way the eponymous song lags at the pace of a dirge beneath the sped-up footage, with Dorothy’s ruby slippers rubbing together like a stridulating cricket.

Since Tailor’s accompanying piece in the exhibition, ‘Synonymous’ (2020), is a sculpture that seems to show the NHS logo trying to bust out of a ramshackle wooden crate on spindly legs, let’s assume that the video is similarly anti-sentiment — at least when it appears as a distraction from the financial squeeze on the public sector.

Samantha Rosenwald, The American Domestic Unit, 2020, coloured pencil on canvas, 35 x 35 cm

Sally Hackett, garlic swans, 2020, garlic and acrylic, 8 x 11 x 10 cm (each)

Ryan Orme, Untitled, 2020, ink on calico, 30 x 41cm

Rebecca Harper, Breathe, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 27 x 39 cm

While Tailor considers public entities, many of the artists’ gazes are fixed on the intensely private, cameras reorientated accordingly. Several works are situated in showers or baths, including Anastasiya Tarasenko’s ‘Rehearsing for “How Are You Holding Up?”’ (2020) — the artist flexing her cheek muscles awkwardly through a series of rictus grins, like she’s forgotten how to smile. Seen individually and out of context, there’s a whole lot of navel-gazing going on; but viewed cumulatively, these works speak of our alone-togetherness.

Roxanne Jackson, Dragon Glass, 2018, ceramic, glaze, luster, 23 x 61 x 33 cm

Roxanne Jackson, Chrome Cat (Silver), 2013, slip cast porcelain, glaze, PVD (metallic plating), 28 x 28 cm (per piece)

Rose Nestler, The Weird Sisters, 2020

Georgina Clapham, Homage to Alexander McQueen, 2020, oil on linen, 42 x 50 cm

While for some, domestic spaces become bridges to other worlds, for others they present more ambiguity. Bambou Gili’s ‘Neighbourhood Sleep Paralysis’ (2020) is a reclining female nude, with ectoplasmic, Hi Viz-coloured skin. A cat — a stoic companion in many of the other works in the exhibition — sits on the woman’s stomach, a sleep demon with devilish ears. Behind closed doors, a heaviness sets in.

As the lockdown measures are eased, weights are lifted and we all flex our smiles ready to meet the world, it’s worth remembering that lines between domestic and public spaces aren’t so clear after all. The world doesn’t end at the front door — but it does unfurl beyond it. Here’s to expanding microcosms.