As working from home has become the norm during lockdown, the boundaries between work and home life are becoming increasingly blurred. Eva Clifford explores how people are stealing back time through ‘revenge bedtime procrastination’ and how modern working patterns could be detrimental to our sleep and health.

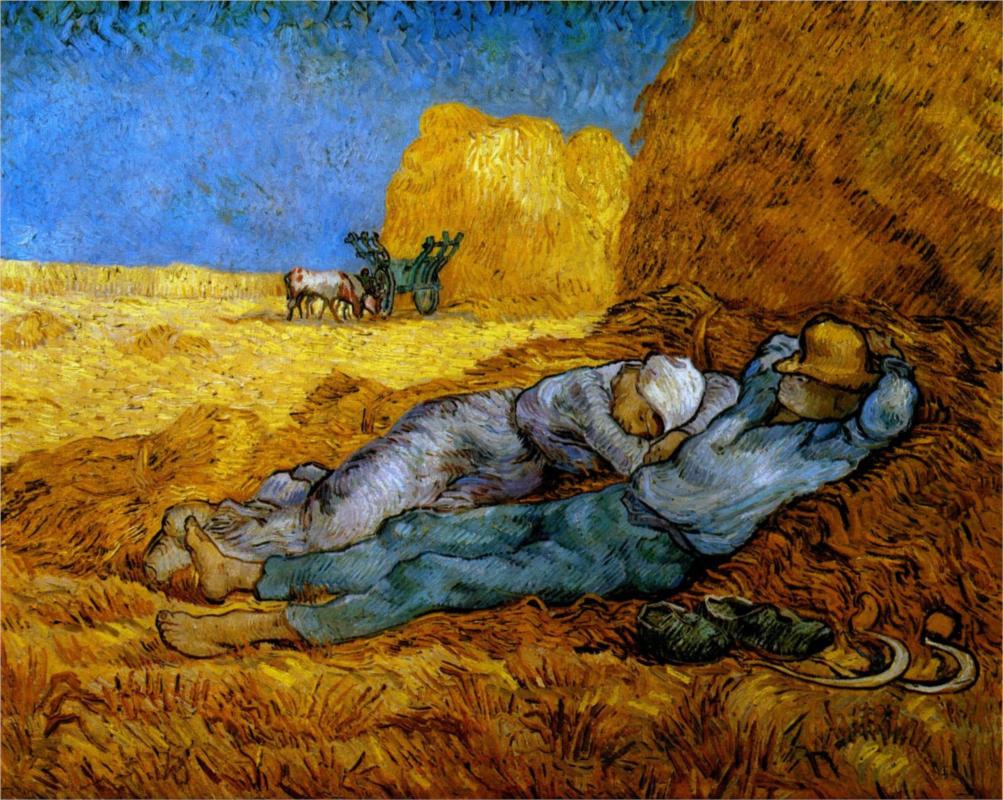

Noon – Rest from Work (after Millet), Vincent van Gogh, 1890, Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

If you’ve ever googled the secrets to becoming a billionaire, three words of advice crop up repeatedly: wake up early. Entrepreneurs insist that an early start is a foolproof key to success and the morning routines of billionaires go something like this: rise early (4am), shower in ice cold water, meditate, work out, go for a run, respond to emails, read the news and neck a smoothie containing twelve different kinds of fruit (all before the sun has barely risen). If this is the case, it’s absolutely out of the question that I will be becoming a billionaire, or even millionaire, in this lifetime.

For as long as I can remember I’ve always pushed the limits of when to go to sleep and no matter how hard I try, my night owl habit is one I can’t seem to shake. To get me to sleep as a baby, my dad would push me up and down the dark lanes of the Yorkshire village we lived in at the time. After several laps he’d return, breathe a sigh of relief when he heard no more sounds coming from within the pram. But on lifting the hood, he’d find two bushbaby eyes staring back, obviously with no intention of sleeping. Although it’s normal for babies not to fall asleep when you want them to, most outgrow their unsociable sleep habits; I never did.

The Long Sleep, Briton Riviere, 1868

At 2am most nights, you can find me at my laptop either writing or deep in an internet rabbit hole. In fact, it was down one of these rabbit holes that I discovered the phrase: “revenge bedtime procrastination” (報復性熬夜, literally: “suffering through the night vengefully”).

The term, which originated in China, went viral last year and describes a trend in which modern-day workers resist sleeping early to seize the freedom of the night hours. When journalist Daphne K. Lee posted a Tweet about it, it was re-tweeted almost 90 thousand times.

“After a day of ‘mum duties’, once the children are in bed, I need some time to myself no matter how tired I am. My husband doesn’t really understand,” someone wrote in the thread.

“I’ve noticed for years that I do this. When I’ve got more free time for myself I can go to bed early and get up reasonably early. When my entire day is meeting other people’s needs/on everyone else’s schedule, I stay up late to have time for myself,” said another.

Clearly, the term resonated.

To better understand sleep procrastination, we can look at how working patterns have evolved over time. In our agrarian past, farm labour began at the crack of dawn. Work was governed by nature (seasons and weather) and people generally went to bed when the sun set.

Historian A. Roger Ekirch argues that before the modern era, interrupted or bi-phasic sleep was dominant in Western civilization.

According to his theory, which is based on evidence from hundreds of ancient texts, adults typically slept in two distinct phases, separated by a period of wakefulness lasting around one hour. It appears that people back then were surprisingly enterprising at this time of night, and used it in various ways: for prayer, reflection, dream interpretation, writing, paying the neighbours a visit, smoking, sex, or for committing petty crime.

Following the birth of industrialisation and the invention of the lightbulb in 1879, the nature of work was revolutionised. People could suddenly work for longer, unrestricted by daylight hours. Then with the arrival of modern technology, work didn’t have to be confined into a single location either; employees were now able to work remotely and even communicate across time zones.

However, despite the advantages that greater work flexibility brings, competitiveness and increased demand are causing our work patterns to extend.

It was after the invention of the lightbulb and during the Industrial Revolution that the nature of work was revolutionised

Our lack of sleep is a slow form of self-euthanasia.

Matthew Walker

In countries where sleep procrastination is most prevalent like China, work culture is extremely demanding. While Chinese law limits the working week to 44 hours, many tech firms enforce the “996 schedule” (working from 9am to 9pm, 6 days a week), which means employees can expect to work up to 72 hours a week. Kids often face immense pressure from parents to succeed, leading many to internalise feelings of inadequacy if they’re not meeting ambitious goals. As a result, young people might be tempted to exploit the night hours to catch up on work – even at the expense of sleep. In fact, a 2018 national survey revealed that more than 60% of people born after 1990 in China weren’t getting sufficient sleep.

Meanwhile in Japan, extreme work habits are having such an impact on the physical and mental wellbeing of its citizens – with a rising number of fatal strokes and heart attacks attributed to overworking – that there is a term (Karōshi) for death by overwork.

When sleep is abundant, minds flourish. When it is deficient, they don’t.

Matthew Walker

From an early age, we’re taught to associate sleeping little and rising early with virtue, despite scientific proof that sleep is vital for maintaining good health. The hours after midnight are “ungodly” while those who wake early are praised.

For many, being a night owl and late riser comes with a stigma of laziness, even if they work just as hard as early risers and get exactly the same amount of sleep. But why is it that some of us seem naturally hardwired to stay up later than others? Could it just be that night owls are driven by an internal clock – one set by genetics not willpower?

Research suggests that our sleep patterns are largely determined by our individual ‘chronotypes’ (natural circadian rhythms) and that night owls and early birds have different patterns of brain activity. In a series of tests, researchers found night owls had poorer attention, slower reactions and increased sleepiness overall. Morning larks were least sleepy and had their fastest reaction time in the early morning tests, while night owls had their fastest reaction at 20:00, showing how night owls are disadvantaged by the “constraints” of the typical 9-5 working day.

Astronomer by Candlelight, Gerrit Dou, 1657-9

Elizabeth K. is a freelance writer based in London. Her bedtime varies from midnight to 4-5am. “I think I have a different circadian rhythm to most,” she says. “I’m not sure what it is, but I feel more creative and more curious [at night]. Maybe it’s the knowledge that all the tasks of the day have been ticked off: work, showering, eating. I tend to find creative flow from 10 pm. I enjoy how quiet the city is. The feeling that few other people are awake. I appreciate sleep more when I am truly exhausted.”

So what’s the solution? How can employers better accommodate people of all chronotypes? Greater work flexibility, it seems, tends to be in everybody’s favour. Managers have reported better performance outcomes and productivity with employees who are allowed more flexible working. Employees can likewise schedule work around their own sleep patterns and family life, harnessing their most productive times of the day (or night).

But Heejung Chung, labour market and welfare state researcher at the University of Kent, argues that having greater autonomy or flexibility over work hours does not always lead to better work-life balance. The more control you give workers, they tend to increase working hours. Her advice is to work smarter, not longer.

It’s not slacking off, it’s just smart working.

Heejung Chung

Heejung believes detachment from work is crucial. “Evidence shows that you need to be able to really recuperate and regenerate in order to be productive, so you need to be physically as well as psychologically away from work,” she says.

“If you were to work till 11pm and then try to sleep, your body hasn’t had time to decompress as you’re still in work mode, so in a way, the workers are doing their employers a favour by [taking a break]. It could be Netflix, yoga… whatever it is, the more you can mentally detach yourself away from work it helps with that detachment and regeneration to be able to actually get back to work and do a great job.”

“Obviously, there’s huge scientific literature around the importance of sleep,” she adds. “A lot of productive idea-making and cognitive processes actually happen during sleep as well – as scientific literature shows – so sleep is really important [too].”

While technology has awarded us greater flexibility in terms of work, our digital addiction is disrupting our sleep and is partly to blame for our sleep procrastination. Studies show that the blue light from our cell phones and computer screens sends alerting signals to the brain and delays the release of melatonin, which controls the sleep-wake cycle. A recent poll by the National Sleep Foundation found that 95% of people use some type of computer, video game, or cell phone at least a few nights a week within the hour before bed. Now in lockdown, we’re spending more time than ever on our screens.

A Girl Asleep, Johannes Vermeer, 1657

Since the pandemic, companies around the world have implemented working-from-home policies, introducing more flexibility into working lives, but also in some cases, further blurring already tenuous boundaries between work and home life.

“For many, because of the insecurity of job loss or career penalties due to this pandemic, because you’re anxious, you might try to overcompensate by working very long hours,” says Heejung.

“Working very long working hours is shown to cause all sorts of problems, and actually science shows that it’s to the point where if you work for very long hours, you actually end up making so many mistakes so that it takes more time to undo those mistakes. It’s much better to try to focus more on work in the short bursts of time that you can, more concentrated without distractions.”

She adds that while some people don’t have the luxury to have those distinct boundaries, try to evaluate how you’re using your time, take breaks and set clear cut off times at the end of your work day. In short, be a better manager of yourself.

The best bridge between hope and despair is a good night’s sleep.

Matthew Walker

In our capitalist society where time is monetised, there’s a mentality that if you snooze you lose. But rest, as everyone knows, is crucial for us. Our productivity also suffers when we’re rest deprived. Not getting enough sleep can have serious health consequences. Margaret Thatcher may have sworn by her four-hour sleep schedule, but she also died of a stroke.

If you’re a night owl like me, it can be exhausting to feel out-of-sync with the rest of society, but you shouldn’t have to feel confined by other people’s ideas of ‘normal’. As technology has brought work into other spheres of our life, it is increasingly difficult to separate work and life. The laptop summons us to do a little more work, reply to one more email. With a work culture that makes us feel one step behind it’s not surprising people are procrastinating on sleep. For those who work predominantly on screens, it’s important to come back and remember you have a body. Get outside. Take a walk. But also go gentle on yourself. Rest should never have to be ‘revenge’.