There’s a chill to the air in Ostend, Belgium, where Léon Spilliaert was born in 1881. Throughout his career, the artist returns again and again to the deserted coastline. Looking out at a great expanse. Searching for something to fill the void inside, it seems.

Through the mists of ambiguity, identification: we’ve all felt alone at one time or another. And that recognition is a prodigious light through all this gloom.

Gallery view of the Leon Spilliaert exhibition. Photo: © David Parry/ Royal Academy of Arts

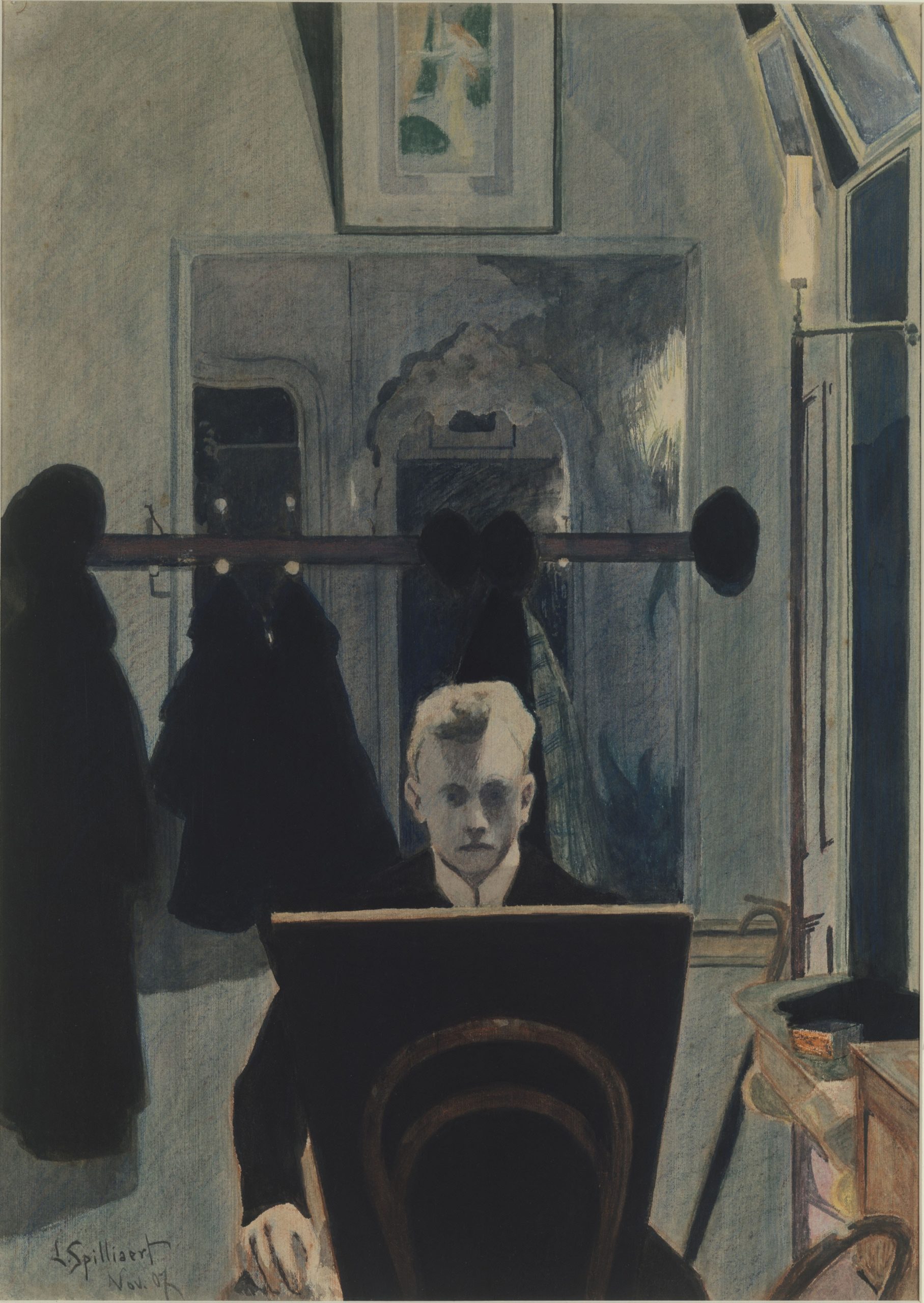

Oh, Léon Spilliaert. Why so blue? A series of self-portraits, as you walk into the Royal Academy’s exhibition: blue notebooks, blue backgrounds, blue jackets. The shock of hair and model cheekbones are ghoulified by Indian ink daubed across his face and enshadowing the eyes to hollows. These portraits of the artist as a young man are only a click away from Spilliaert’s later depiction of a ‘Human Skull’ (1914). Tenacity and insecurity ebb and flow from the frames.

Oh, Léon Spilliaert. Why so blue?

The atmosphere of angst and loneliness here reminds me of Edvard Munch. À la ‘The Scream’, Spilliaert’s ’The Gust of Wind’ (1904) shows a woman howling by a stark harbour, the squall of the title lifting her skirt Marilyn Monroeishly. Though, unlike Marilyn, the woman’s hands are not coquettishly pulling it down, but riveted to her sides. Paralysed.

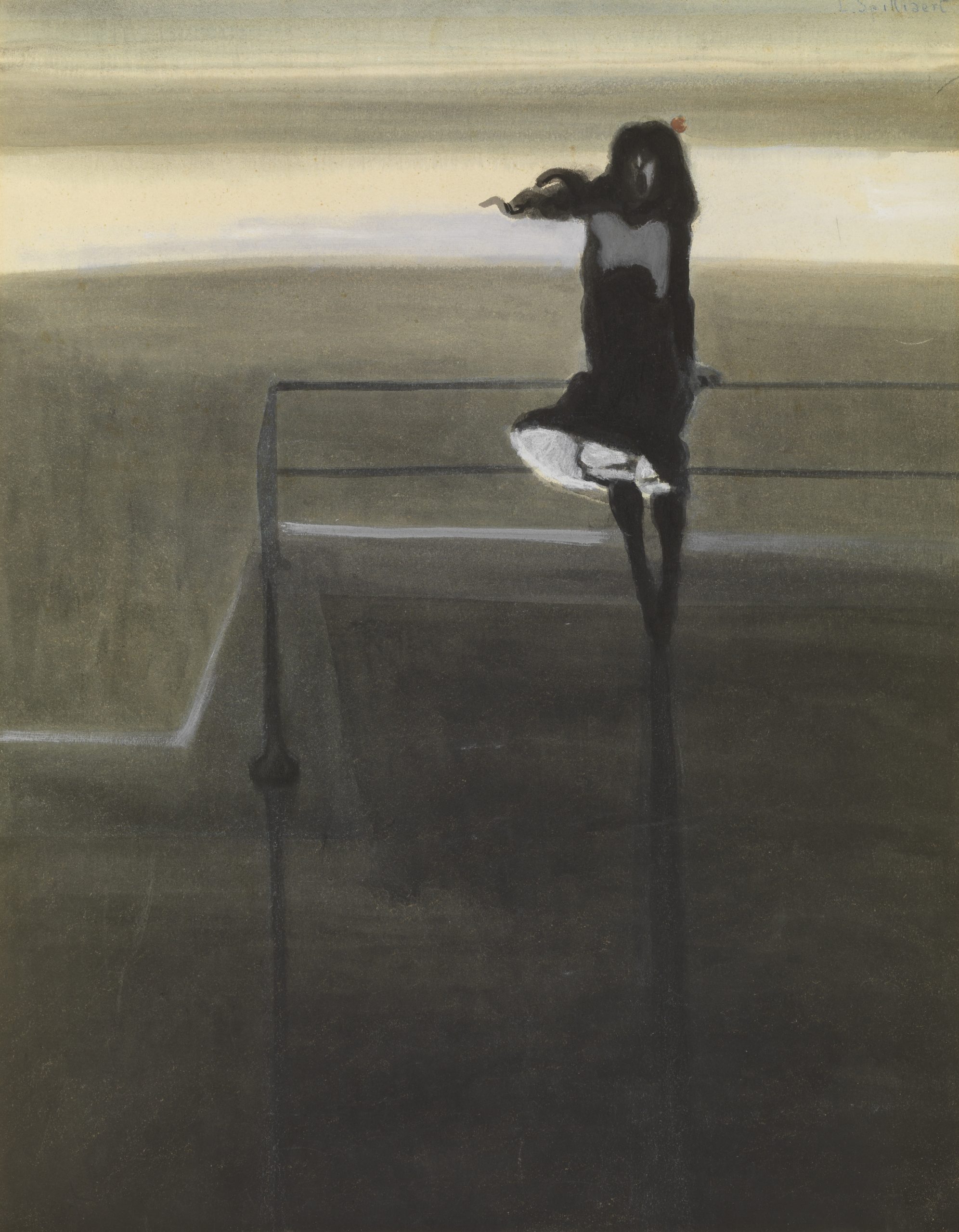

Leon Spilliaert, Woman at the Shoreline,1910. Indian ink, coloured pencil and pastel on paper, 49 x 60 cm. Private collection. Photo: © Cedric Verhelst

Her lean, near-black silhouette, skirt and hair blown sidelong, cuts an almost typographic shape — a 1, or an I. Along with the regimented horizontal lines of cloud, sea and guardrail, the scene should be legible as a ruled notebook. Yet the feeling of melancholy, the mystery of the woman’s horror, seems too profound for words.

…the feeling of melancholy, the mystery of the woman’s horror, seems too profound for words.

From paralysis to movement: in ‘Hofstraat, Ostend’ (1908), the blurriness and strong perspective of buildings rising up either side of us evokes a sense of rushing – towards a pinprick of light, and a bilious cloud. Meanwhile, this distant lantern casts an improbable streak of light back towards us (again, you can read a letter: a skinny and existential ‘i’). The combined effect is much like a filmmaker’s dolly zoom inducing vertigo.

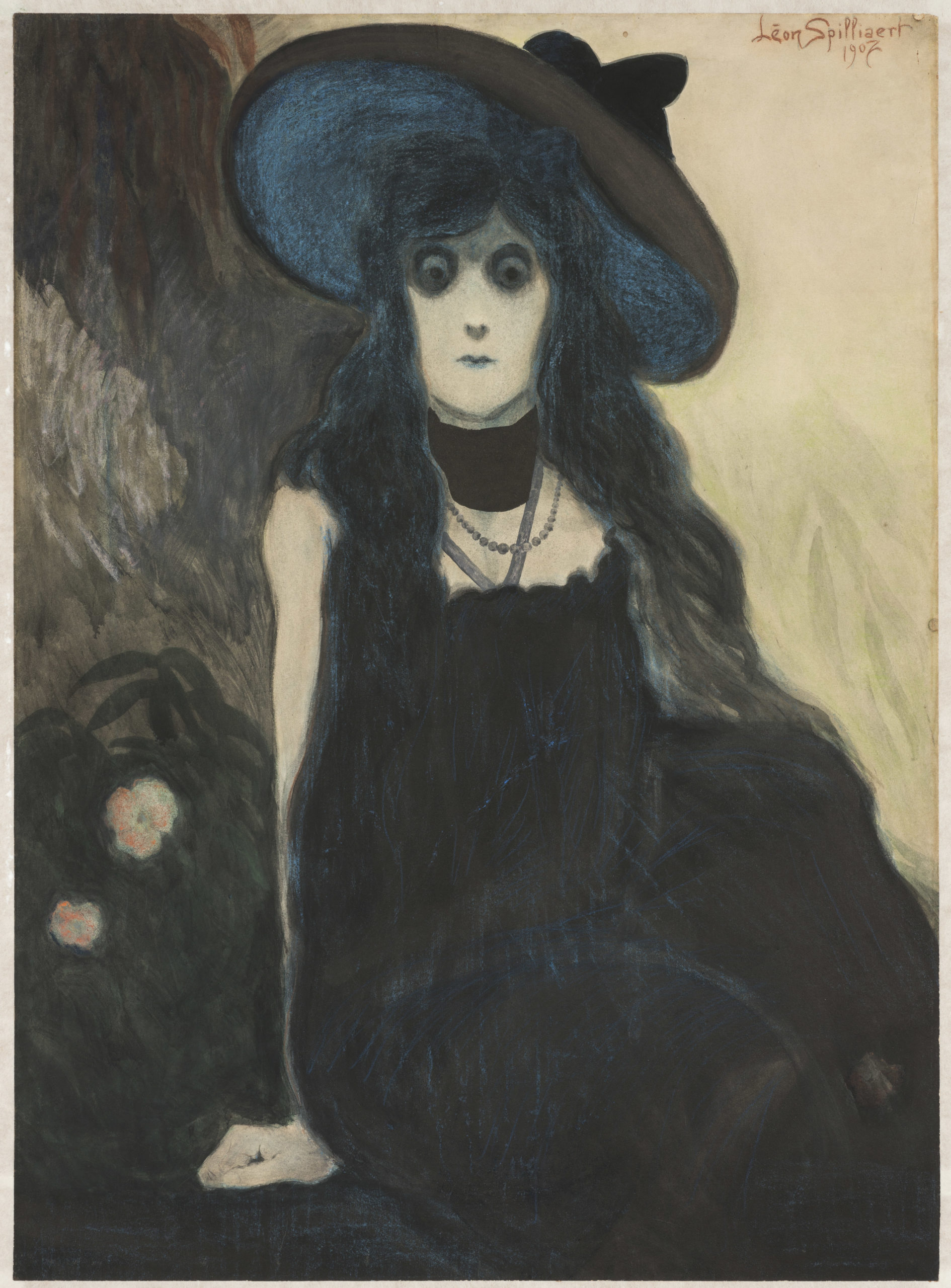

Leon Spilliaert, The Absinthe Drinker, 1907. Indian ink, gouache, watercolour and coloured chalk on paper, 105 x 77 cm. Collection King Baudouin Foundation, entrusted to the Fine Arts Museum of Ghent, Belgium, © Studio Philippe de Formanoir

Spilliaert, Leon (1881-1946): Self-Portrait, 1907. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art***

Nearby is ‘The Royal Galleries at Ostend’ (1908), a neoclassical arcade on a greyscale Belgian beach. Seen from a different angle, the row of columns might represent order and civilisation; Spilliaert’s viewpoint, however, creates an unnerving velocity. The columns are seen so obliquely that they seem to stack, gathering momentum before rushing off to a vanishing point.

Cut the painting down the centre vertically, and you’d have one painting of the pillars and another of a still and empty shore; from where we stand, we have one foot in civilisation, the other at the edge of the earth. An example of how difficult it is to get purchase in Spilliaert’s forsaken world.

Leon Spilliaert, Young Woman on a Stool, 1909. Indian ink, pen, coloured pencil, coloured chalk and gouache on paper, 70.3 x 59.9 cm. The Hearn Family Trust

A painting called ‘Alone’ (1909), showing a woman seated in a spacious yet characterless attic, is lonely enough – though somehow less so than others of Spilliaert’s, for all their ambiguity. There’s almost no accounting for why ‘Beach at Low Tide’ (1909) evokes such a strong feeling of despondency, for example.

A curving fin-shaped body of water on a darkening beach, whose indigo sand leads out to thin layers of sea, sits beneath sky and cloud covering the top quarter of the canvas. Could the colour blue be making me feel, well, blue? Or is it the way my eye is drawn to the horizon’s light? How thin that strip of light seems. How far away.

Leon Spilliaert, Dike at night. Reflected lights, 1908. Indian ink wash, pen and coloured pencil on paper, 48 x 39.4 cm. Musée D’Orsay. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Leon Spilliaert, The Shipwrecked, 1926. Watercolour, gouache, Indian ink and pen on paper, 54.2 x 75.3 cm. Private collection. Photo: Luc Schrobiltgen

Spilliaert uses shape to enact a certain experience of loneliness; namely that of reaching out to someone, only to be rebuffed. Breakwaters are great, isosceles shards. A stretch of boardwalk has neat wooden planks that seem to merge into a steady conveyor belt.

Spilliaert uses shape to enact a certain experience of loneliness; namely that of reaching out to someone, only to be rebuffed.

Ripples in the sea are a detailed pattern of wavy lines reminiscent of a contour map. These shapes are so sure of themselves, so seductive — and daring for Spilliaert’s time — that they draw us into the paintings. Only what do we do when we’re there? These are bold geometries, and they lead nowhere at all.

Take ‘Girls in the Waves’ (1908): three simple, curving white lines (the waves) are immediately pleasing for the eye to follow. The middle line is especially appealing to trace, with its alluring squiggle where the girls are standing. The girls, however, are being blasted by an impossible wind, one that would have to have been shot directly from the sea to make their hair stand upright.

The girls are being blasted by an impossible wind, one that would have to have been shot directly from the sea to make their hair stand upright.

The viewer is disarmed and the girls, in their spectral white dresses, risk being lifted off the face of the earth. It’s like we’ve been welcomed in, only then to be left to fend for ourselves — like the host who invites you to a dinner party, but won’t give you any clue as to where you’re supposed to sit.

Leon Spilliaert, A Gust of Wind, 1904. Indian ink wash, brush, watercolour and gouache on paper, 51 x 41 cm. Mu.ZEE © www.lukasweb.be – Art in Flanders vzw. Photo: Hugo Maertens

There’s an old adage in advertising that goes something like: Don’t sell a deckchair, sell an afternoon in the sun. To my ear, it’s not a million miles away from what poet Stéphane Mallarmé says, in a letter to his friend, is the goal of the symbolist movement: ‘to depict not the thing, but the effect it produces.’ When Léon Spilliaert is painting portraits, he’s painting what it is to be a self.

There’s an old adage in advertising that goes something like: Don’t sell a deckchair, sell an afternoon in the sun.

When he’s depicting lighthouses, they’re standing in for what is to be alone. Capturing seascapes, reaching for the feeling of paddling at a shoreline; puzzling at a horizon that seems as vast as it is evasive. Come on in. Though the water’s not very warm.