★★★☆☆

The following light essay offers some musings on the recent Lucian Freud: New Perspectives exhibit at the National Gallery, but few grand conclusions or fresh insights on the artist. Fitting really, because that’s precisely what the boldly declared ‘New Perspectives’ curators unnecessarily tried to do.

This latest display of the late London School artist’s paintings is available to see in a new ‘pay-what-you-can’ admissions scheme, with donations as little as £1 accepted. The trouble with it though, and the issue all curators worldwide have at some point in their gallery’s calendar, is to market afresh a hugely well-known artist’s work to a public that knows them as a household name. Such is it with Freud, whose biography itself is almost as, if not more, notable than the painter’s work. It’s also an incredibly fascinating part of the Berlin-born Jew’s oeuvre, as it should be for every artist. To be told to behold a piece of art in isolation or without given knowledge of its creator is a non-starter.

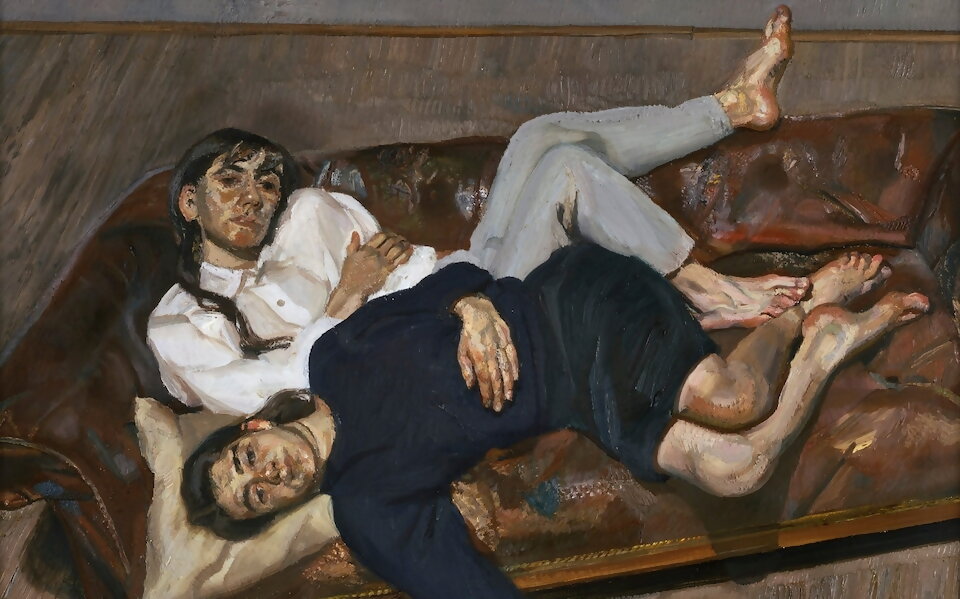

Lucian Freud’s Bella and Esther (1988, detail) Credit: Lucian Freud Archive/ Bridgeman Images/Private collection

And so this is one of several problems that New Perspectives claims it’s trying to tackle, by trying not to focus solely on the life chronology of Freud, but then ends up doing just that because we need to know the context of each painting. Thematically, they’re arranged under labels such as ‘Power’ (Freud’s portraits of wealthy benefactors, including one of Lord Jacob Rothschild which fails to capture the billionaire banker’s ghoulishness), and ‘Death’ (the declining health of the artist’s elderly mother is documented in her final years in small black and white sketches, culminating in a clinical inspection of her corpse).

Lucian Freud’s Naked Girl (1966) Credit: Lucian Freud Archive/ Bridgeman Images

The works increase in size as we move through the rooms of the National Gallery’s oldest building, until we’re finally met with the apotheosis of Freud’s naked figures (Freud preferred the term ‘naked’ to nude as it proscribes honesty and vulnerability to the definition) in frames taller than all of us.

I was kindly told by the art historian who showed us around, after I put it to him there appears to be no ‘new perspective’ to be had here, that they were trying to move the focus on Freud’s obvious eroticism toward something more wholesome and intimate. But Freud chose not to do that, for almost the entirety of the second half of his career. This was a man who died at 88 and probably had as many lovers. The nakedness for Freud wasn’t just the frank vulnerability of his subjects, but a celebration of erotic profanity, which he did expertly, performing a delicate balancing act to avoid lurching into pornographic territory. True, Freud could portray intimacy to some effect on the expressed of these ‘nakeds’, but more often than not this was better embodied in his clothed sitters.

Lucian Freud’s portrait of the Queen was completed in 2001 and celebrated by The Guardian

And what of Freud’s portrait of the Queen, much-vaunted in some circles when Her Majesty sat for it over several days? It’s placed next to David Hockney’s tired likeness, an area of the gallery in which punters are reminded not to get too close. The attempt by Freud is the most embarrassing stunt of his career. ‘Probably the best royal portrait of any royal anywhere for at least 150 years,’ said The Guardian in 2001 when it was revealed, confirming two things: The Guardian is bankrupt in both aesthetic taste and political reason. The portrait is inaccurate, deliberately unflattering, overly masculine, and small in stature to force through some sort of artist-first, subject-second commentary.

Lucian Freud is rightly considered a master in manipulating texture, something he paradoxically practised heavily during his early creative years when trying hard not to reveal any material clues in paint. This and his bold authenticity should be saluted, as should his ability to imbue his art with his own eerieness. But a brilliant conveyer of emotion and intimacy he is not. It takes more than stripping somebody down to their buttocks in a studio resembling a crack den to cleave off their mask and see them rather than merely take look. This is something the National Gallery has attempted to deceive visitors with – to extract the biography and erotic obsession of Lucian Freud is to extract the soul of the artist. Still, it’s worth a quid if you go on a Friday evening.