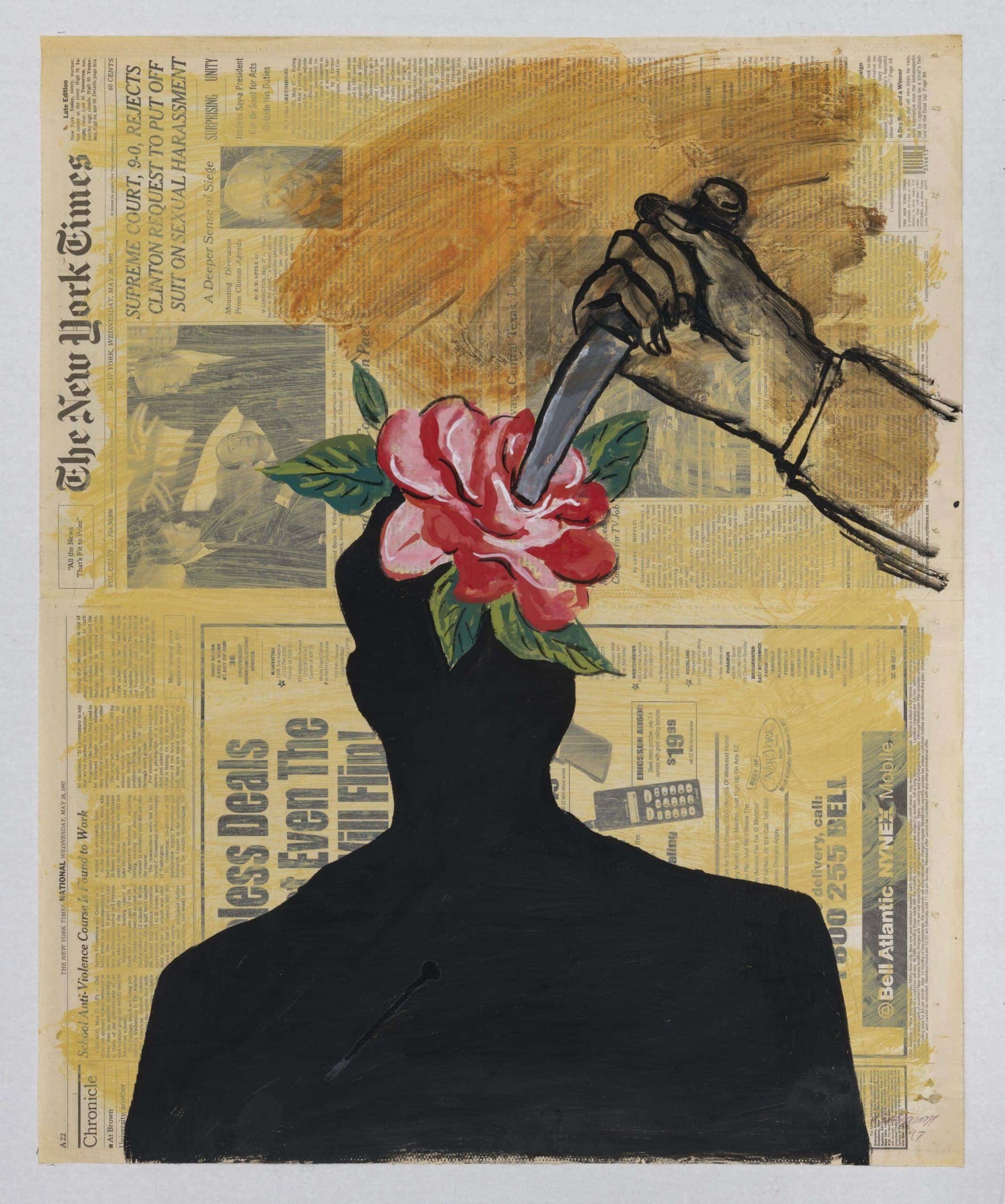

In 2020 and the grip of a global pandemic, it’s easy to sympathise with Nicky Nodjoumi’s urge to paint over the news – nonetheless, it’s something the artist has been doing for years. Rarely seen, let alone exhibited, Taymour Grahne Projects holds the results of a practice which became part of Nodjoumi’s morning routine: breakfast and brushes with the New York Times.

Tue 2 Dec 97

Nicky Nodjoumi was born in Kermanshah, Iran, in 1942. Studying art first at the University of Tehran (too mimetic for his tastes) and then at the City College of New York (too abstract), Nodjoumi’s practice has always taken a decidedly particular path. Feted internationally as well as in his home country of Iran, Nodjoumi’s explicitly political paintings drew criticism (not to mention harassment) from the regime’s secret police when he returned to Iran in the 70s.

When a major exhibition of his work was organised at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in 1981, Nodjoumi held fast to his convictions. Filling the gallery with depictions of the Shah’s brutality and his religious autocracy’s hypocrisies, Nodjoumi’s show was promptly shut down by the Revolutionary Guard. The artist fled to America, where he has lived ever since.

ArrayThe mother of invention

While the artist’s newspaper works certainly suit his ongoing pursuit of politically active practice, they first came about out of necessity. Having relocated to New York and working in the loft he shared with his wife and daughter, Nodjoumi couldn’t work at the scale – or with the materials – he was accustomed to. In 1996, the artist painted the front page of April 6th’s New York Times, and didn’t stop for three years.

Without a passport, in exile from his native Iran, the daily paper became Nodjoumi’s window into the world. The works it inspired vary in terms of their explicit connection to their particular day’s headline; some seem to respond directly, while others offer a playful – or deadly serious – alternative to the messages on their found host-materials. At Taymour Grahne Projects, The New York Times Drawings 1996-1998 is Nodjoumi’s first London solo show: 49 works are on display, providing ample opportunity to lose oneself in palimpsest after palimpsest.

ArrayBreaking News

Nodjoumi’s New York Times Drawings bring their own stories – literally, in black and white – to bear on the artist’s interventions, inflected in turn by past and current world events in a fluid symbiosis. For their part, Nodjoumi’s gestures neither obscure nor highlight their surface medium. Each takes its title from the date (and city) it was made, opening a layer of time-and-place to hold paint, pigment, personhood: New York Times, Monday, December 9, 1996; New York Times, Wednesday, May 7, 1997; New York Times, Wednesday, May 28, 1997.

At Taymour Grahne, a rare self-portrait sits alongside sketches of family, friends, drawings based on photos from the papers as well as allegories for the situations described between their pages. In a style which hovers between delicate and cartoonish, Nodjoumi oscillates between insistent stencilling and light outlines drawn freehand.

ArrayLion, twice

Some motifs appear again and again; on both August 11th 1996 and January 1st 1998, for instance, Nodjoumi paints a lion – central to the Iranian flag before the 1979 cultural revolution – on top of another animal. A deer, maybe a horse? Whatever the specifics, eagle-eyed historians will recognise the composition from innumerable ancient bas reliefs, most notably at Persepolis, in which ferocious lions spar with bulls.

For all their surface similarities, though, Nodjoumi’s renderings of that unmistakable configuration have less in common than might first appear. In the first, a black-outlined predator sits astride its green quarry; skewering them both is a red arrow, locking the animals together and referencing the colours of the Iranian flag. In the second, the lion takes up its hunting stance again, clinging to its prey and poised to deliver its killer blow.

Look closer, and it’s not just claws and flesh enmeshed – this lion is fucking its prey, while a lewd, floating red face offers its tongue to the lion’s mouth. Certainly, it’s tempting to read such specific – and curious – apparitions as explicitly symbolic, ready to express a very specific idea indeed if only they could be decoded. And, while their newspaper backgrounds add to that allure, they fox it too.

ArrayLife on Mars

Let’s return to August 11th 1996. That day, the New York Times reported on Turkey’s intent to sign a ‘gas deal’ with Iran in a move characterised as ‘defying the US’. Could those countries be depicted in Nodjoumi’s brawling animals? Well, the paper also reported on ongoing violence in Bosnia, then-President Bill Clinton imposing new sanctions on Iran and Libya, NASA finding evidence of ancient microbial life on Mars, Zambia’s copper mines and the fall of the fishing industry in British Columbia, and, and, and.

Meanwhile, January 1st 1998’s New York Times (the background for Nodjoumi’s lion-deer-2.0) reported on the backlash to Davoud Mirbagheri’s film ‘Snowman’ in Isfahan, Iran, which raised devout eyebrows for its depiction of cross-dressing. Could the scandal there have inspired the artist’s explicit drawing on top of it? Well, perhaps – but again, that paper also features a story about escalating tensions between the US and Iraq, Kenya’s general election and updates from the French police on Princess Diana’s death.

Which of these stories ought we try and project into the front page’s surface paint? All, one? None? Appealing though it is to map a Nodjoumi’s drawing onto a single column and be done with it, the paper’s hubbub beneath practically dares you to presume such easy resolution. Within this small selection alone, the artist breaks from the strictly topical, pivoting from politics to the deeply personal to illustrate a leap which isn’t so long after all.

ArrayNO VIOLENCE

January 15th, 16th, 19th, 20th, 22nd, 23rd, 26th, 27th, 28th, 29th and 30th 1998 see Nodjoumi on a spree – paper after paper is emblazoned like a campaign poster, each proclaiming something or other forbidden; lost. NO MEANING. NO LIE. NO SUCCESS, NO HUMOR, NO WONDER, NO CONSPIRACY, NO COMMENT, NO CONDITION, NO EVIDENCE. NO DIRECTION, NO LIMITS, NO DEAL.

While the motif is woven throughout his three-year practice, that spate of proclamations in early 1998 – reminiscent of newspaper headlines themselves – offers one alternative means of translating the world into words and pictures. If other works from the series, featuring lions or family or floating faces, are less clearly legible – well, isn’t that just as it should be?

New York Times, Sunday, September 21, 1997. White paint, thinly applied and with visible brushstrokes, makes a background for blue. Blue makes a background for a boy. The boy’s head is cleaved in two. His eyes, displaced just enough to be disconcerting, gaze from his world into ours – but the veil between those spheres is far from watertight.

ArrayBoy in blue

Take the black and white photo from the newspaper’s surface, visible through the layers of paint which support Nodjoumi’s head – there, another face gazes into the viewer’s eyeline. Illustrating a story headlined ‘Civil Rights Anniversary Points To Unfinished Tasks’, both the article and its image aren’t just from our world – they’re there, in print, to help us navigate it.

In life as in art, the distinction between our subjective experience and the one narrativised for us, by artists or politicians or the newspapers which report on them, is murky to say the least.

Friday 19 Sep 97

By layering his cloven blue boy on top of the Times’ front page, Nodjoumi insinuates his protagonist’s primacy – whoever he is, and whether he exists in the same realm as The News, he’s Nodjoumi’s front page. Whether he speaks to you is neither here nor there; after all, who could claim to care deeply about every newspaper headline they see?

The New York Times drawings perform a smart flourish, individually but never more than when in concert as here. Whether in paint or print, one human being mediates meaning for another the second they pick up a brush or a pen. Nodjoumi highlights that gulf, filled eagerly with human interpretation, by building on it.

ArrayStory as substance

If stories are made of anything, symbolically speaking, it’s paper and ink. Using those physical materials, the artist leverages the tales themselves as conceptual substance. In a publication like the New York Times, where narratives are compiled for their supposedly universal relevance, Nodjoumi proposes his own priorities to deflate the ones decided for us.

There are big stories, and there are small ones. There are grand ideas we share with the world, and quiet convictions we nurture internally. Those categories of large and little, public and private, are perhaps most compelling at their intersections – as Venn diagrams rather than circles. Certainly, it’s only with hindsight that we come to grasp whether a given headline will be looked back on as the beginning of a movement which changes the world, or just a flash in the pan.

ArrayFrom daughters to despots

Stranger still is what event touches which life; I’m sure the most important moments in yours weren’t relayed in national news, or more than half what’s reported in a given national newspaper’s headlines touches you at all. And, as with politics, so with people. From ancient symbols of fractured kingdoms to light, loving sketches of a daughter across the kitchen table, our lives are made of both.

Breaking news! I lost my job! Trump’s been reelected! The cat got hit by a car! He said he didn’t want to! The EU won’t negotiate anymore! I found that necklace! Every day, we write our own headlines, record internal interviews, and compile a personal front page; with Nicky Nodjoumi, in part at least – it is one man’s made manifest.