One female painter we will hear more of this winter is Paula Modersohn-Becker, about whom Uwe Schneede has written a well-illustrated survey. An exhibition of Modersohn-Becker’s art will open at the Royal Academy (12 November 2022-12 February 2023) alongside art by Käthe Kollwitz, Gabriele Munther and Marianne Werefkin.

Half-Length Portrait of the Sculptor Clara Rilke-Westhoff,1905© Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen

A London training

Paula Becker was born in Dresden in 1876 to a large middle-class family. Paula’s first intensive art training came in St John’s Wood Art School when she came to London for an extended stay over 1892-3. Her appetite whetted, and she undertook more art courses in Bremen and later in Berlin.

Moving to the artists’ commune of Worpswede in 1898, Becker became a minor member as a newcomer to an existing group. She learned from fellow painters of similar outlooks and where she met (and painted) poet Rainer Maria Rilke. In 1901 Paula married Otto Modersohn. She did not see marriage as slowing her down. “Just because I am getting married, that is no reason not to become somebody.”

Two Girls by a Birch Trunk,c. 1092© Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen

Still Life with Asters and Tomatoes, August 1906© Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen

Her early works are scenes and figures from the domestic life of peasants, frontally facing and as simple as possible. The colours are muddy and muted, befitting the aesthetics of social realism and affinity with the life of the rural poor. She was reticent about displaying her art, and a rare showing of her art led to a scathing review, which prompted her to withdraw her art from the display.

Following the French

In 1899 Modersohn-Becker visited Paris, the centre of avant-garde art, to study and view Old Masters and the Impressionists. When she returned to Worpswede, she was much more confident and knowledgeable. Her new paintings were of trees and children, sometimes combined. She endowed her subjects with the clumsy intensity found in children.

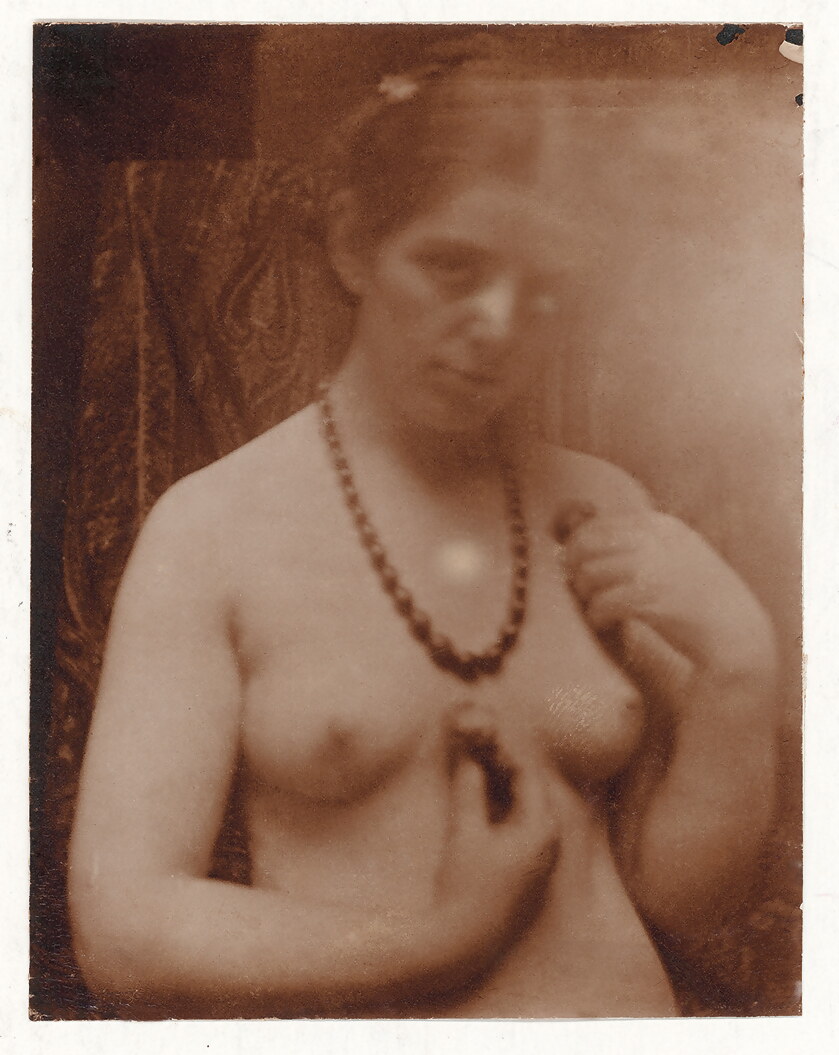

When she revisited Paris in 1905, she sketched people on the street. The best of her art is the oil portraits showing children’s heads. These are more sensitive, careful and less self-conscious than her more celebrated self-portraits. The nude self-portraits show her admiration for Gauguin and the cult of primitivism. The book reproduces nude photographs she had taken of herself in preparation.

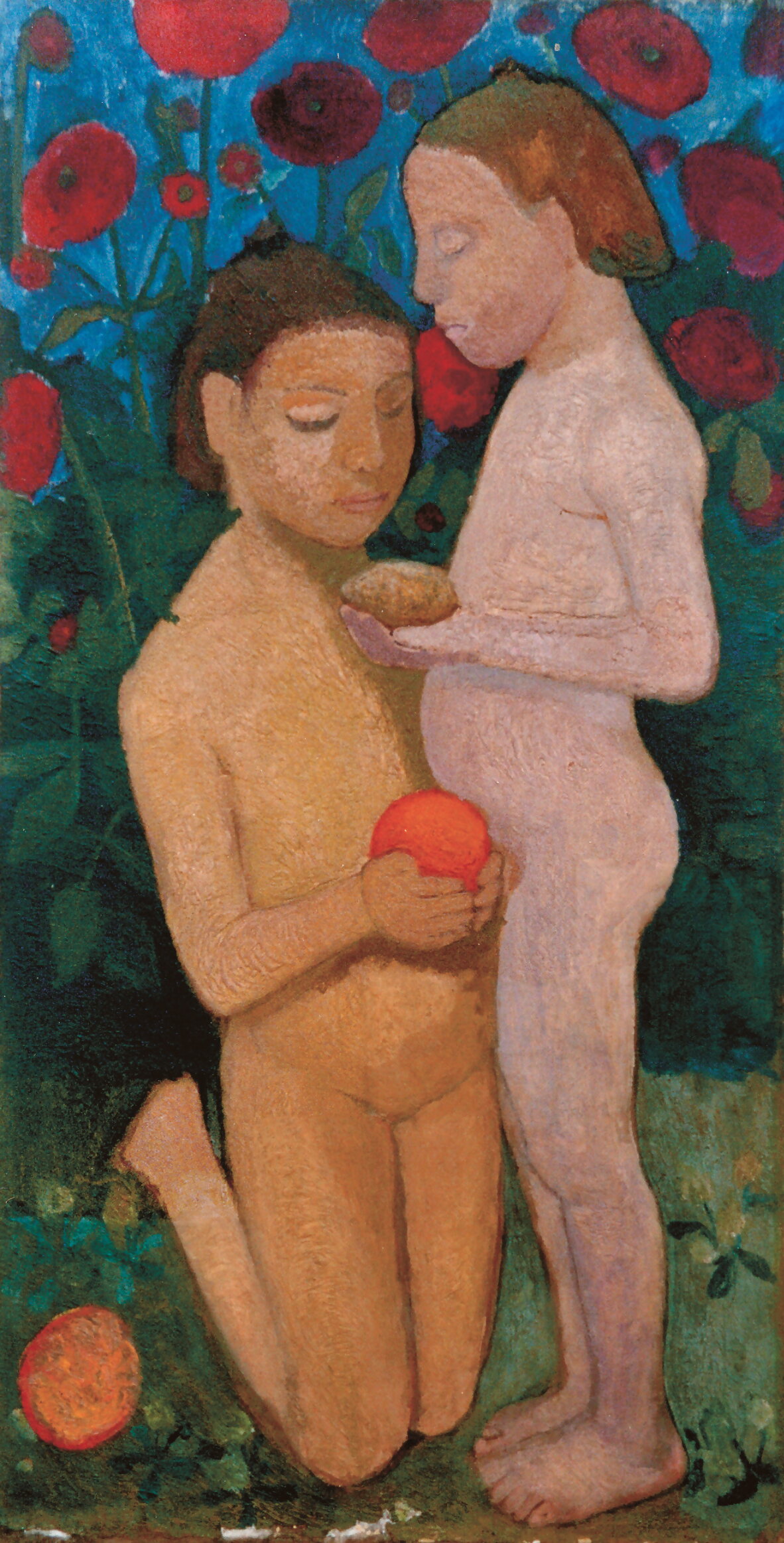

Standing and Kneeling Girls Nude in Front of Poppies II, May-June 1906© Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen

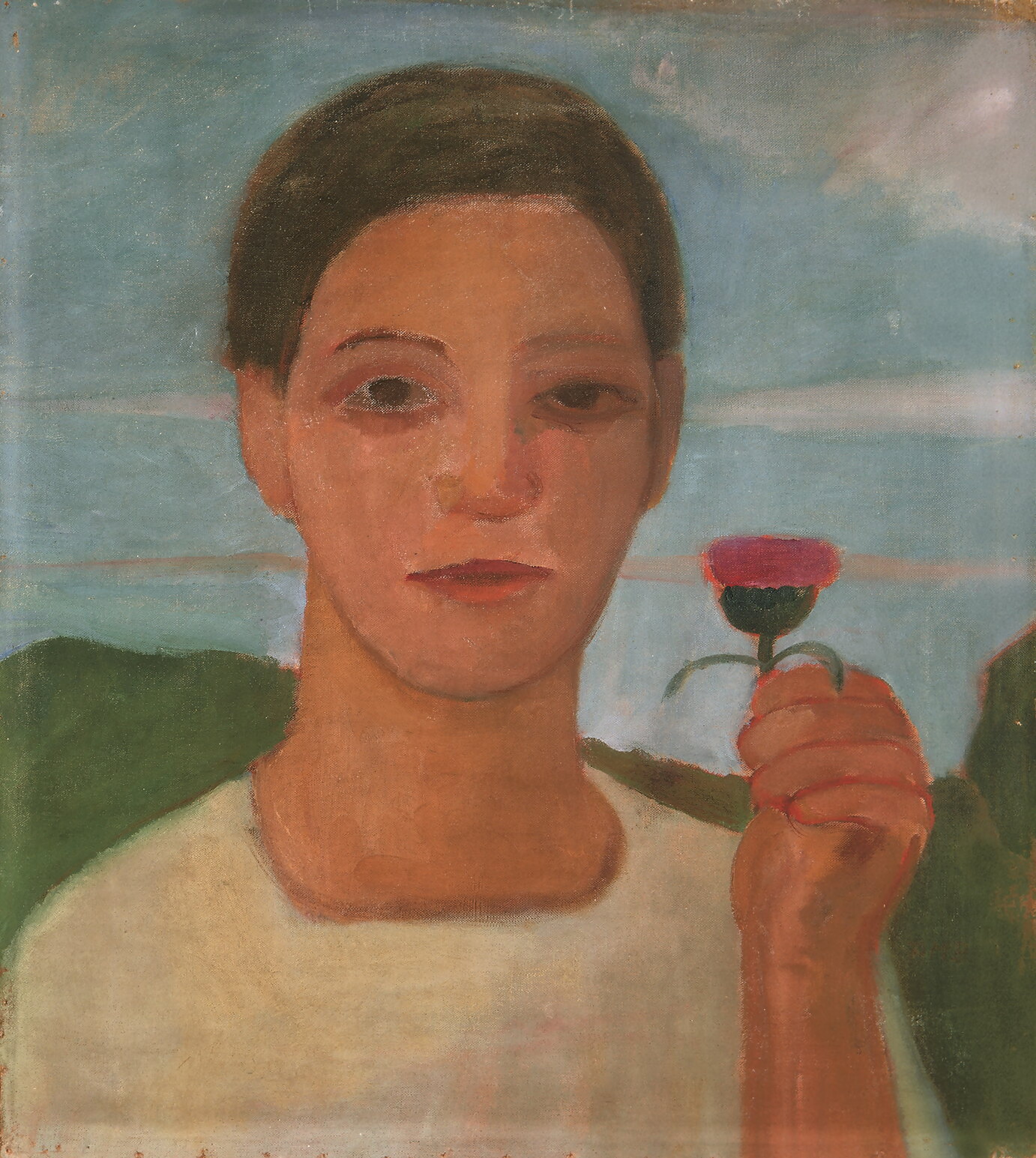

Portrait of Sister Herma with Artichoke Flower in her Raised Hand,April-May 1906© Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen

In 1906, she separated from her husband and moved to Paris permanently, seeking to pursue her career. “I am Me, and I hope to become more and more Me.” Her self-portraits have attracted much attention as iconic images of woman-as-artist, not least from feminists. However, they seem overrated – somewhat stilted.

Dead at 31

In 1907, the artist (now reconciled with her husband) returned to Worpswede pregnant. She gave birth to a daughter on 2 November 1907 and, on 20 November, died of pregnancy-related thrombosis.

There is poignancy when an artist dies young. Modersohn-Becker died just as it seemed she was poised to become a star of the emergent modernist movement. Yet, looking at her art, which is modest in many respects, one wonders if she would have made much of an impression without the verve of Frida Kahlo or the meticulousness of Gwen John.

Self-Portrait as a Half-Length Nude with Amber Necklace I, summer 1906© Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen

Paula Modersohn-Becker, half-length nude, photo by Herma Becker (?), May-June 2006© Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen

While the book has biographical information, the emphasis is heavily on art. Schneede’s book is an excellent guide to the artist and the development of her oeuvre, but many readers will come away with only a slight impression of her character. This book is an ideal grounding for those planning to see the London exhibition of Modersohn-Becker’s art this winter.

Uwe M. Schneede, Paula Modersohn-Becker: A Life in Art, Thames & Hudson, 2022, hardback, 240pp, fully illus., £25, ISBN 978 0 500 02562 8