★★★★☆

Above: John William Waterhouse (1849–1917), Study of Two Nymphs for ‘Hylas and the Nymphs’, 1895–6, Black chalk with some heightening on faded grey paper, 30.7 × 51 cm

Visitors to the current exhibition Pre-Raphaelites: Drawings & Watercolours (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, closes 27 November) will encounter some surprisingly contemporary sides to these Victorian artists. Having affairs, taking drugs, chasing famous actresses, developing new fashion and spending long hours outdoing each other with the most outré interior design, these Victorians were like the denizens of today’s coolest districts.

Who were the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherood?

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) were a group of British artists who worked from the 1850s to around 1900 who used different styles that resembled England’s pre-Renaissance (hence “before Raphael”) aesthetic. The throng of artists had varied interests but came together in a loose association as the PRB under the guiding influence of author, art critic and (extremely skilled) amateur artist John Ruskin (1819-1900).

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–82)

Head of a Woman (attendant for ‘Astarte Syriaca’), 1875

Coloured chalks, heightened with white, on pale green paper,

54.4 × 40.4 cm

The works on paper in this Ashmolean’s exhibition are rarely shown due to the light sensitivity of the delicate pieces. The display includes art by all the most well-known of the PRB: Gabriel Dante Rossetti, John Everett Millais, Edward Burne-Jones, Ford Madox Brown, William Morris, John William Waterhouse, and William Holman Hunt. There are many pieces by less famous artists too, including women.

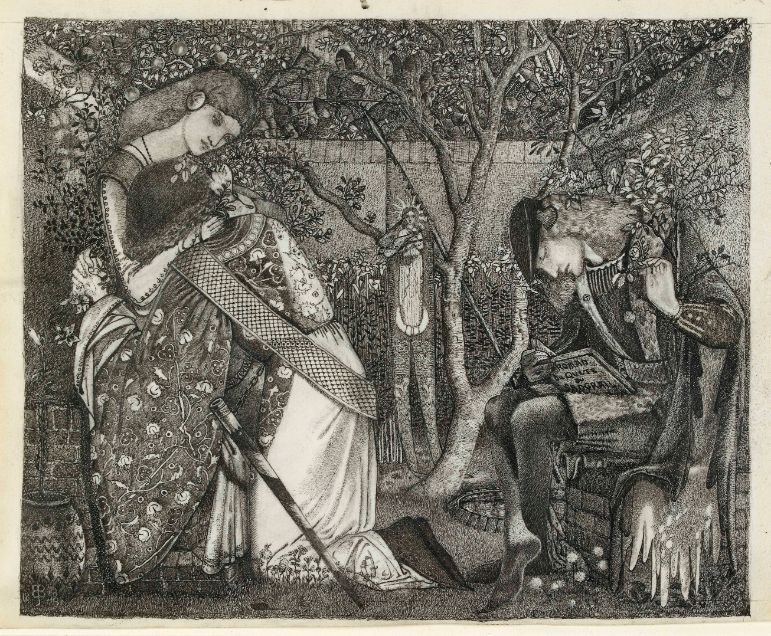

The PRB often painted episodes from English myth. These include an evocative watercolour of the death of an old knight, where the dying man, in full armour, is carried to a wooded valley to see his final sunset. Elsewhere, Medieval-style designs by Burne-Jones on stained glass and murals accompany an exquisitely detailed ink drawing of a knight and lady in a Medieval garden with lines as fine as hairs.

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1833–98)

The Knight’s Farewell, 1858

Pen and black ink over graphite on vellum, 17.6 × 24.2 cm

Simeon Solomon (1840–1905)

Two Acolytes Censing: Pentecost,

1863

Bodycolour on paper mounted on canvas, 40.3 × 34.8 cm

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–82) The Day Dream, 1872–8

Pastel and black chalk on tinted paper, 104.8 × 76.8 cm

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844– 1927)

Cloister Lillies, 1891

Watercolour and bodycolour on paper, 45 × 36 cm

Other subjects are taken from ancient myths and romantic poetry, inspiring PRB verse written by Morris, Rossetti and Rossetti’s sister Christina, who became an acclaimed poet and writer of fairy tales. Morris was the founder of the Arts and Crafts movement and was deeply involved in designing clothes, furniture, wallpaper and other aspects of interior design that would resemble crafts of England’s pre-Renaissance.

Carnal passion and drug-taking in Victorian Britain

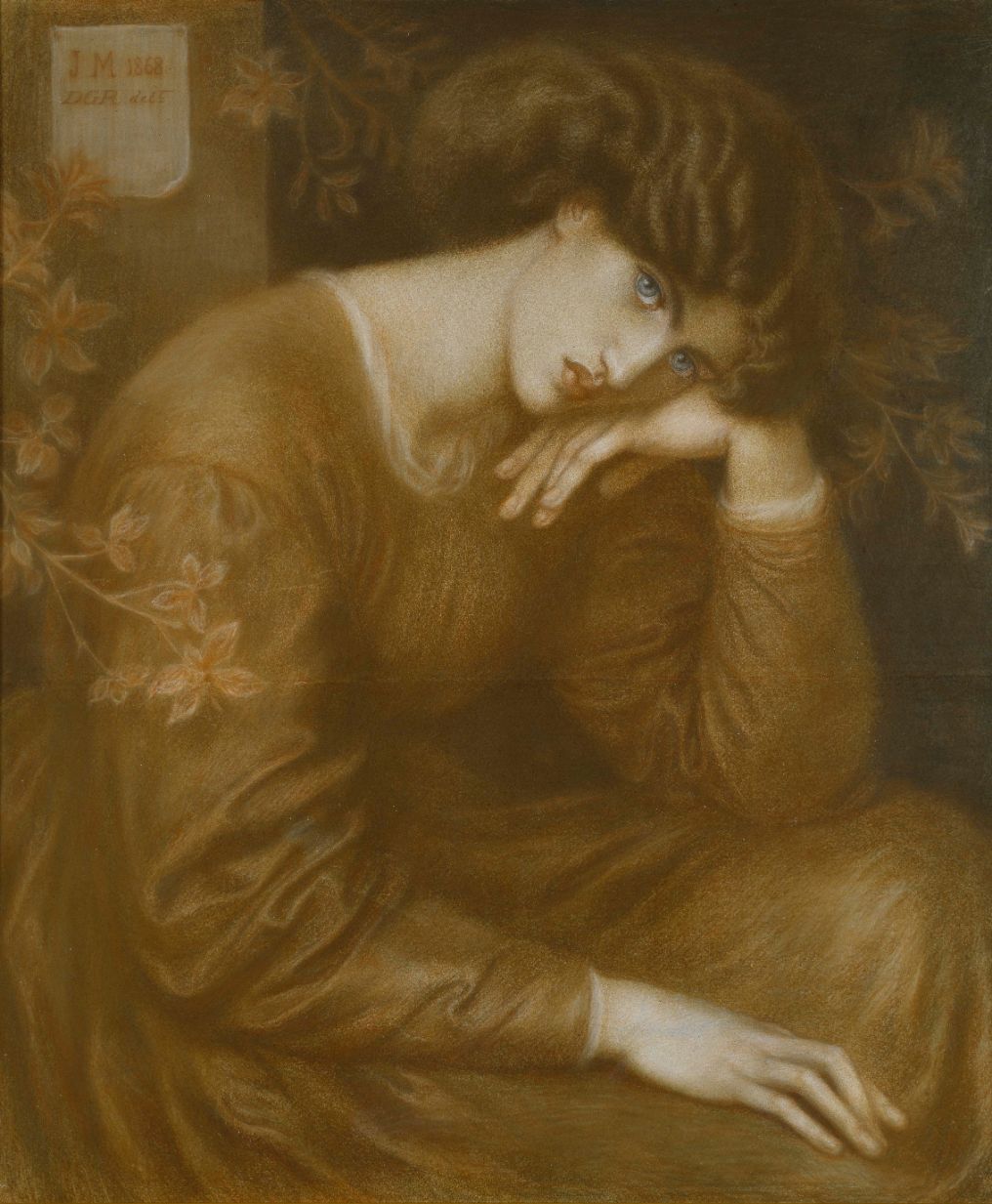

For all their adulation of gallantry and chivalry, the Pre-Raphaelites were just as susceptible to carnal passion as we are today. Artist-poet Rossetti came up with the term “stunner” to describe a woman who leaves men stunned with her beauty. Rossetti saw actress Louisa Ruth Herbert perform on stage and arranged for a sitting so he could draw her. She had the attributes that made Rossetti’s stunners: high forehead, full lips and strong rounded chin.

Also covered in the Ashmolean exhibition is the scandalous tale of Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal. Spotted by Rossetti, she became his model and later wife whilst studying to become an artist herself. Her surviving art is accomplished and deliberately archaic, albeit a bit stiff. Pictures by her in this display are promising rather than gripping. She became the template of Rossetti’s “doomed beauty”, featured (in idealised form) in later paintings before finally overdosing on laudanum (opium in alcohol).

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–82) Reverie, 1868

Coloured chalk on tinted paper, 86 × 72 cm

John Ruskin (1819–1900)

Study of the Plumage of a Partridge, 1867

Watercolour and bodycolour over graphite on card, 28.2 × 39.9 cm

John Ruskin (1819–1900)

Study of a Velvet Crab, c. 1870–1

Graphite, watercolour & bodycolour on grey-blue paper, 24.5 × 31.5 cm

Any grieving Rossetti sought to do had to wait. Lizzie was buried with the only copy of Rossetti’s love poems and so when he wanted to publish the poems, the only way was to exhume Siddal’s body and retrieve the manuscripts. This was done by Charles Howell (art collector and friend of Rossetti), who required permission from the Home Secretary. There is an impressive coloured-chalk portrait of Howell in the show, drawn by Frederick Sandys.

Keeping it in the PRB family

After Lizzie’s death, Rossetti and Jane Morris had an affair. Jane, wife of William Morris, was active in the design and production of Arts and Crafts objects. There is an impressive ink drawing of her in an Icelandic costume that William brought back from his visits to the island. The simplicity and flowing lines contrasted with the tight corsets and elaborateness of Victorian fashion.

The wives and models of the PRB often designed (and made) their own clothes that contrasted with the style of today and their flowing loose gowns became a key feature of the art and lifestyles of the group. Jane and Rossetti were estranged by Rossetti’s addiction to chloral hydrate. In his last years, while in drug-induced torpors, Rossetti was haunted by visions of Lizzie.

Ford Madox Brown (1821–93)

King René’s Honeymoon: Architecture, c. 1861

Brush with black and grey wash on paper, 45.5 × 31 cm

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–82)

Sir Lancelot’s Vision of the Sanc Grael:

Study for Painting in the Oxford Union, 1857

Watercolour and bodycolour over black chalk on paper, 71 × 107 cm

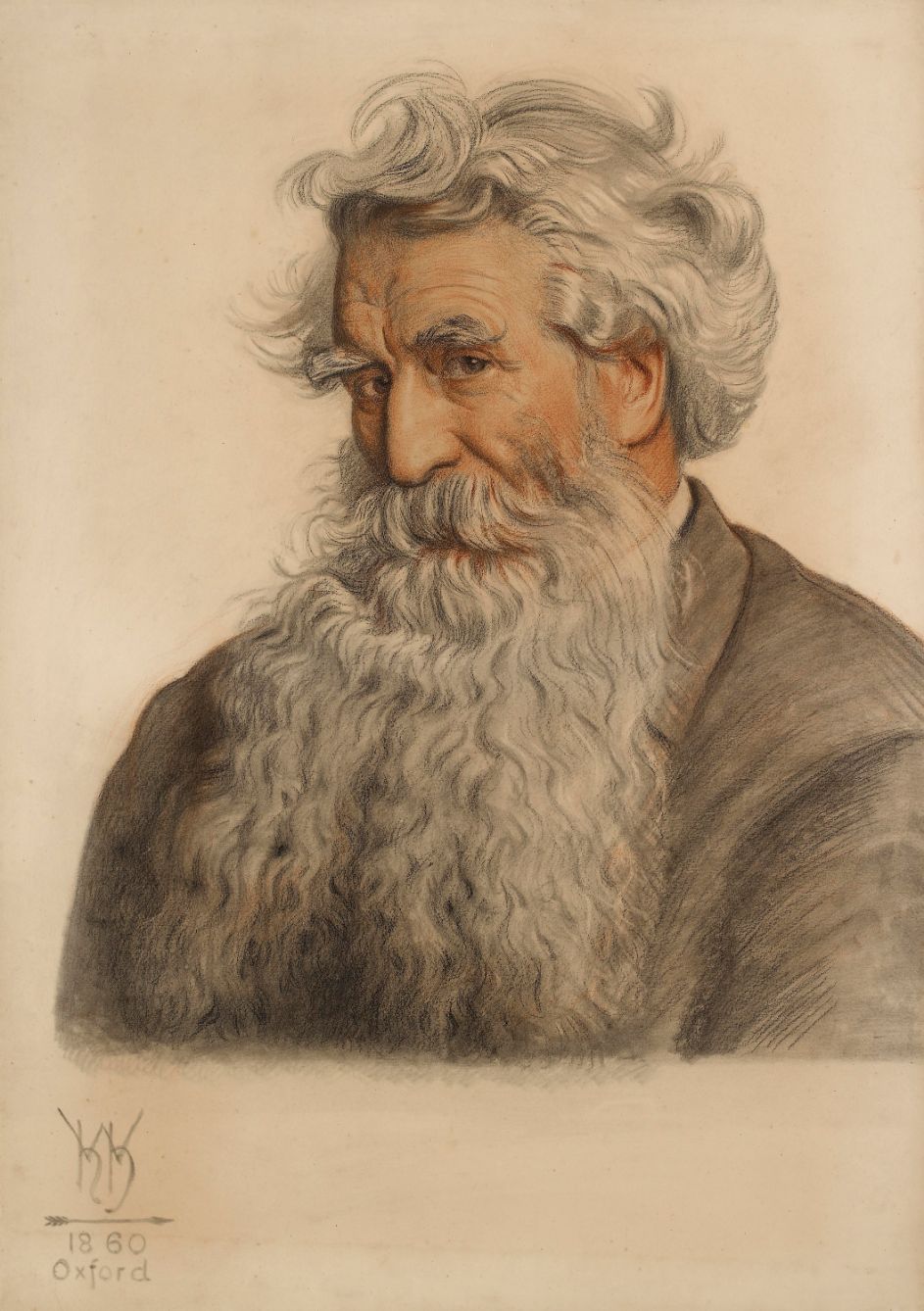

William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

Thomas Combe, 1860

Red and black chalk on paper, 67.6 × 47.9 cm

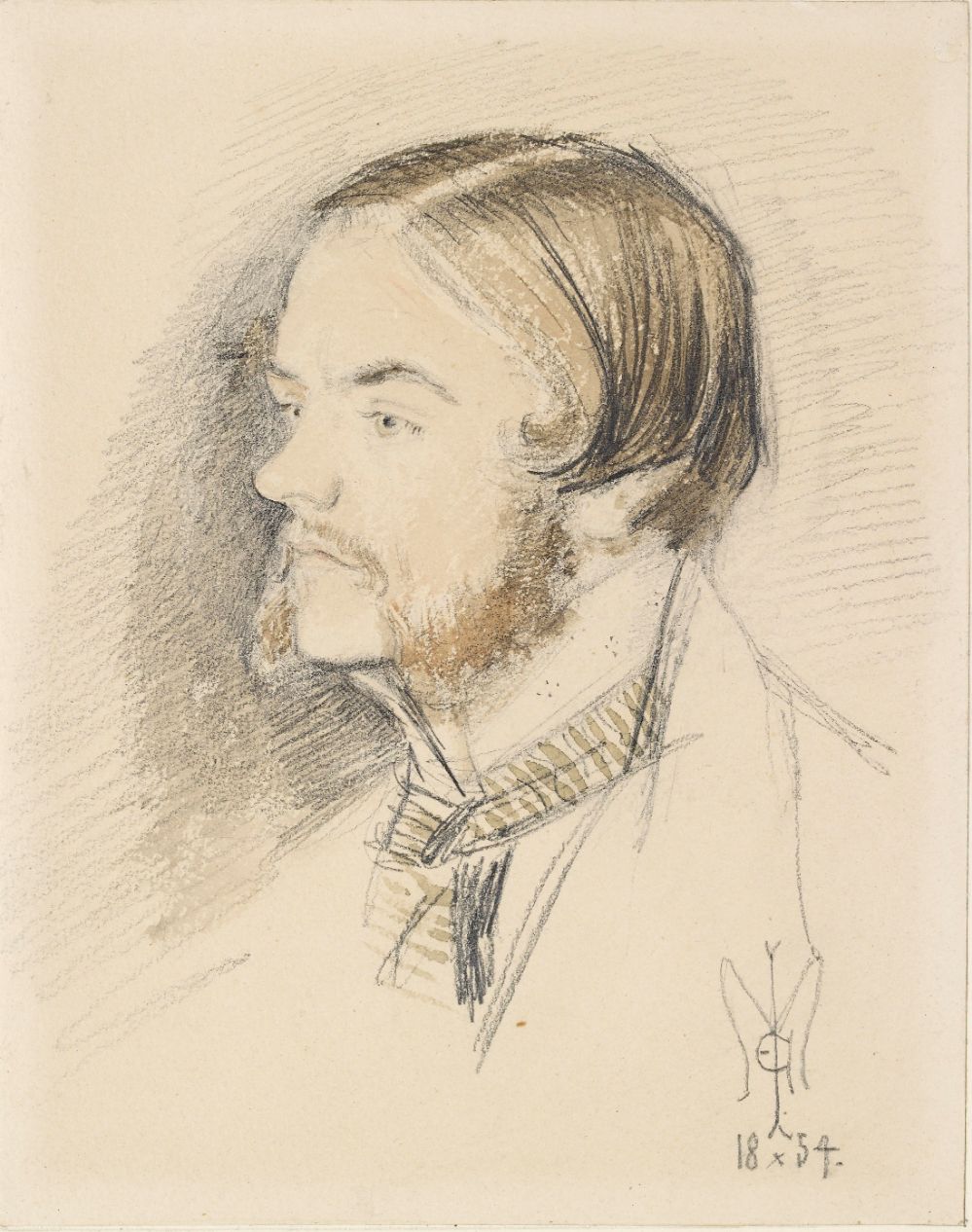

Sir John Everett Millais (1829–96)

Portrait of William Holman Hunt,

1854

Black chalk with brown wash on cream paper, 22 × 17.5 cm

Millais painted a famous full-length portrait of Ruskin (1853-4, also in the Ashmolean) standing by a stream, featuring minutely described plants, water and stone, which followed Ruskin’s instructions for artists to pay the greatest attention to the natural world. The initial pencil sketch is in the exhibition. Ruskin applied his own advice, as visitors will see from his drawings of stone, plants and animals. Ruskin’s watercolour of a crab is strikingly lifelike and acutely observed. Of the lesser-known artists George Price Boyce’s watercolour landscapes stand out as compact, rich in colour and detail.

We see ourselves in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Do not forget to visit the permanent collection, which has a good collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings. Some preparatory drawings and watercolours in the exhibition are for paintings in the main galleries. There you can find armchairs made of coloured stone, commissioned and owned by PRB artists. They look incredible and are incredibly uncomfortable.

Another aspect of modern attitudes can be found in a small painting of the Holy Land. It was made by painting in watercolour over a photograph – a decidedly untraditional approach. Mixed in with the use of ancient techniques and materials, we find reference to photographic sources.

However, despite modern elements, we can find aspects that do make the PRB distant from us. They admired Christian ideals; they had (or respected) classical education and were knowledgeable about history; they believed in the power of high culture; they took poetry seriously. Contradictory, inconsistent and failing to live up to their aspirations, the Pre-Raphaelites are closer to us than we might have thought.

Pre-Raphaelites: Drawings & Watercolours is on at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, until 27th November