The director of BlacKkKlansman (2018), Chi-Raq (2015), and Malcolm X (1992) is back with Da 5 Bloods (2020), out now on Netflix. Four Vietnam vets return to South East Asia to exhume their beloved squad leader and the gold he helped them to hide. Old-timer buddy movie meets polemic, in this urgent and scrappy exploration of the legacy of war and racial injustice. Interstitial flashes of history, shoot-outs, and soliloquy are just some of its many flourishes.

ArrayOn 31 May, Spike Lee premiered a new short film titled 3 Brothers — Radio Raheem, Eric Garner and George Floyd. Lasting little over a minute, it’s some of the most affecting footage you will ever see — and chances are you’ve already seen it. The film stitches together footage of three African-American men, each of whom is asphixiated by police. Two of the men are sadly all too real, while the third, Radio Raheem, is a character from Lee’s 1989 feature film Do the Right Thing.

Although fictional, Radio Raheem was based on a real man, Michael Stewart, a graffiti artist who died following police brutality in 1983. In case Lee’s point wasn’t stark and clear enough, 3 Brothers opens with text: ‘When Will History Stop Repeating Itself?’

A week later, Da 5 Bloods arrives on Netflix. A little longer, at just over two and a half hours, Lee’s feature picks up where the short left off. We follow four African-American Vietnam veterans, returning to the place where they were once comrades-in-arms, ostensibly to recover the remains of their platoon leader ’Stormin’ Norman’ (Chadwick Boseman) — but also to exhume a buried cache of gold. It’s not so much a return to war, as a reckoning with the fact that, for some, the war never ended.

Da 5 Bloods opens almost as directly as 3 Brothers, with an agitprop montage of footage from the Vietnam War and the American Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and 70s. ‘America has declared war on black people,’ says civil rights activist Kwame Ture, the morning after Martin Luther King Jr’s 1968 assassination.

ArrayLee is not afraid of being blunt, nor does he hesitate to turn the mood on a dime. Shortly after the veterans — Paul (Delroy Lindo), Eddie (Norm Lewis), Otis (Clarke Peters) and Melvin (Isiah Whitlock Jr.) — touch down in Ho Chi Minh, they visit a bar called Apocalypse Now. We find ourselves in the midst of an intertexual hangout movie, with Otis busting out the funky chicken to Marvin Gaye’s ‘Got to Give it Up’.

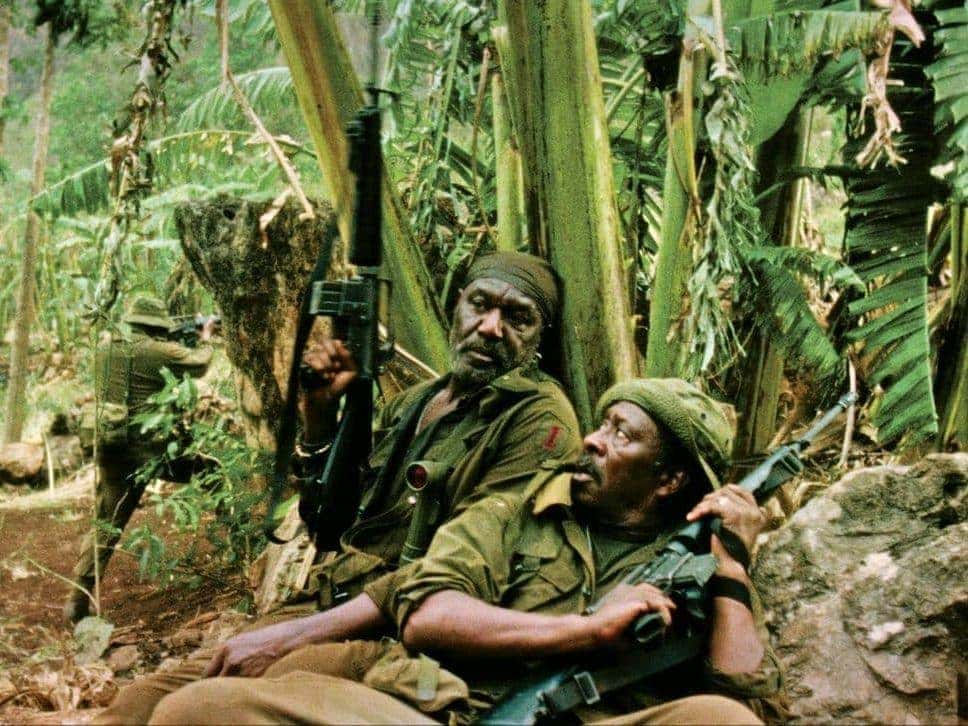

All four are haunted by visions of ‘the American War’ (as it’s known in Vietnam) and by flashbacks to Norman (‘our Malcolm and our Martin’). These flashbacks to combat in the jungle trade widescreen for a square format and 16mm film. Lee makes no attempt to de-age the veterans, all creased faces and beer bellies, while Norman remains perpetually frozen at the age he died.

Just as Lee doesn’t mind foregrounding artifice — we’re all grown ups, who get what’s up when the aspect ratio switches, aren’t we? — he doesn’t mind borrowing scenarios from previous films, all the while making the ‘bloods’ mouthpieces for a smorgasbourd of riffs and ideas: from discussing the whiteness of previous Vietnam films like Rambo to unvarnished rehearsals of theme, like when Paul says, ‘We fought in an immoral war that wasn’t ours, for rights we didn’t have.’

As the bloods make their way into the heart of the jungle, you can see several Chekhov’s Guns a mile off, but they’ll wrong-foot you all the same and yank the film in the direction of Tarantino-esque chaos. Yet, if Quentin Tarantino’s is a revisionist cinema — cathartic revenge porn for the marginalised — then Lee’s is restitutional, galvanising, and hopeful.

ArrayLee’s project is to bring the role that black Americans played in the war to the forefront of political consciousness and thus redefine heroism as such. Although undeniably vital and well observed, the focus on heroism leads to a fair bit of macho male bluster. Then suddenly, around two hours in, Lee pivots from the experience of black heroism to the human experience of blackness, and from directness to detour, when Paul delivers a monologue straight to camera.

Delroy Lindo is electric. Frayed around the edges, wearing his soiled MAGA-hat backwards, Paul stares at the viewer, unleashing the full force of years of trauma. No longer a mouthpiece, he contains multitudes. His grief, anger and inability to forgive himself are palpable.

A part of me wishes the whole film had turned around this psychically scarred, embittered, Trump-supporting veteran. There is such raw and haunting tragedy here — a person scarred by society who turns to selfish individualism, even against his own interests — as to justify its own feature, without the ensemble (that’s by no means to say that the all-star cast don’t deliver.)

Then again, there is a time for subtlety and individuals, and then there’s time for collectivity and radical engagement; for telling it straight. Da 5 Bloods might seem prescient in the wake of George Floyd’s death and the subsequent protests over racial injustice, but part of Lee’s message is that it shouldn’t: history has been repeating itself for some time, and, left unchecked, it will continue to do so.

The way that Da 5 Bloods ends, however, suggests change is possible. Lee leaves us with the words of Langston Hughes: ‘America never was America to me. And yet I swear this oath, America will be.’