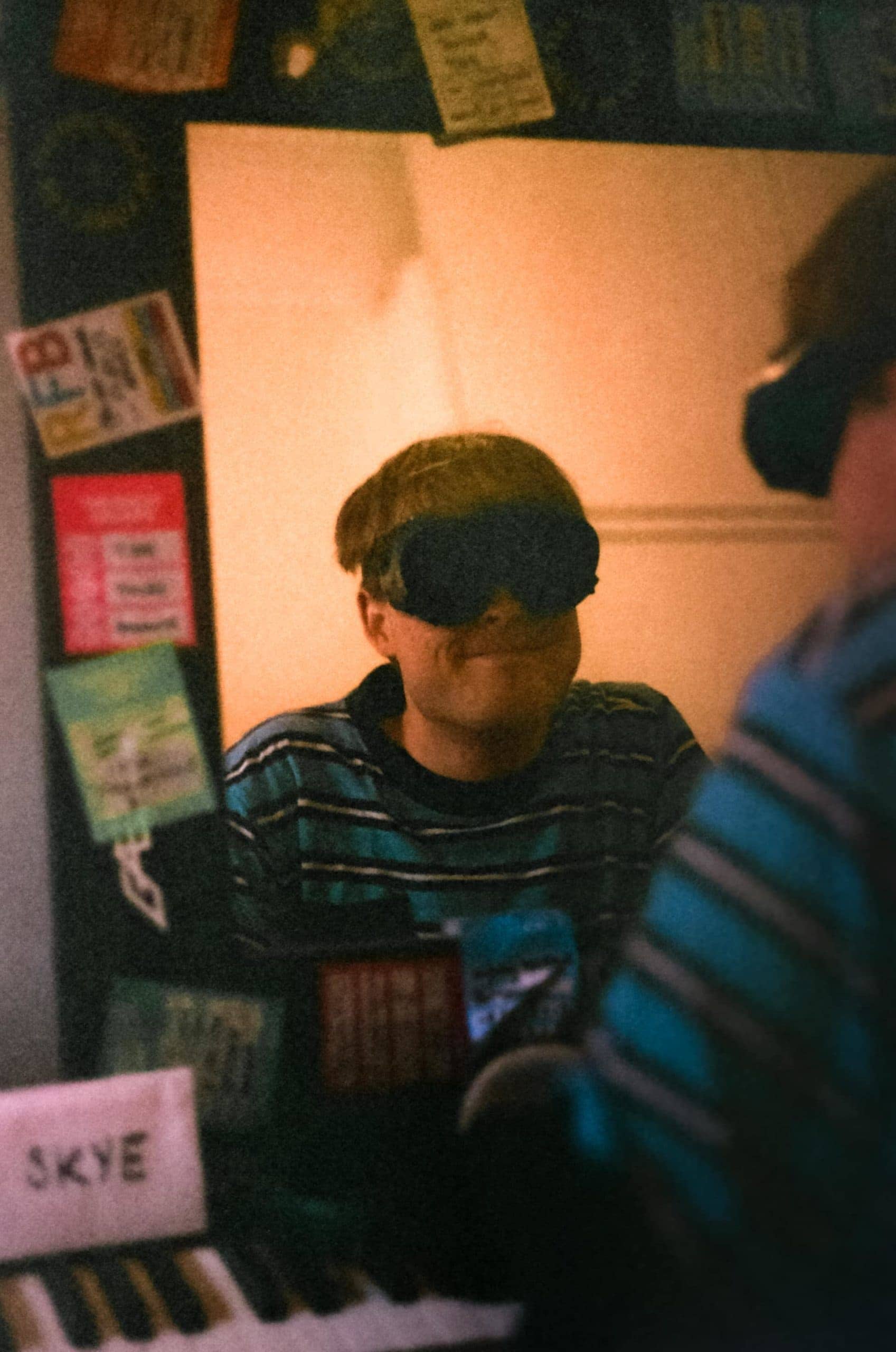

One of half of London’s idiosyncratic pop duo Jockstrap, Taylor Skye is making musical might of his own. Managing to bridge the unlikely worlds of electronic and musical theatre, we speak to Skye about touring with Injury Reserve and the (un)importance of lyrics.

A neat metaphor – if a little forced – for the incapability of knowledge to displace the full experience. Yet that’s the world Taylor Skye, who I meet there for a rather lame lime soda, presently operates in; as a student of Guildhall he is truly learning his craft, and enriching his education with live performances, some of which have been at this very venue, where now Lord Tennyson’s poetry give us a side-glance.

Another, just two weeks prior, was at the nearby Shacklewell Arms, where he demonstrated his curious mix of styles: some of an autotuned, Soundcloud sadboy, some with a James Blake-esque intensity, and, to close the set, he offered us a Rufus Wainwright-style piano finale.

Music just sank into my blood throughout the last twenty years.

The young singer and producer, who also makes one half of the duo Jockstrap, along with fellow student Georgia Ellery, is a natural performer with an impressive ability to stitch these all together into a complete performance.

His parents, perhaps unsurprisingly, were both singers in the West End, with a passion for music and an ability to entertain, which, Skye says, “just sank into my blood throughout the last twenty years”.

“It’s not actually that much when you’re on stage, though,” he adds, despite the constant wiring and re-wiring his performance presented, “but there is a technical thing I like. I mix quite a lot of music and that’s mostly technical stuff; not always, but a big part of it is technical, where you need to make sure everything exists in the right place.”

Being in the right place is something, it seems, Skye has a knack for. So much so that Jockstrap was fortuitous enough to have toured last November with Arizona hip-hop trio Injury Reserve.

Being in the right place is something, it seems, Skye has a knack for – Jockstrap toured last November with Injury Reserve

After playing on the same stage at Iceland’s Airwaves Festival and resolving sound checks together, the two groups got talking. “And then,” Skye explains, “everyone at that festival stays in the same hotel, so we went back and started hanging out.”

“Jimothy Lacoste was playing after them and they hated Jimothy Lacoste – we bonded over that a little bit. (I don’t actually hate [Lacoste] – they just didn’t like his whole attitude, which is not to speak to anyone.)”

“Injury Reserve came to London a few days after and were about to release their new album. I played them their new album in my room and we just kept in contact. They did this tour and it just made sense for us to join them – we’d just been hanging out.”

‘Just been hanging out’. Sounds familiar for this calm, warm, affable character. Jockstrap itself was born when the creative flames of both Skye and Ellery united in their first year at Guildhall in a similar organic vein.

Injury Reserve came to London and were about to release their new album. I played them their new album in my room

“We just clicked and started making music quite quickly – we just bonded over the music thing. It was quite smooth. Jockstrap is Georgia writing songs and me producing, basically.”

“It’s rare to find people like that. I’ve done quite a lot of sessions and it’s a rare thing to find someone you just click with. It’s like we don’t have to explain things to each other, it’s just: ‘obviously, I get what you’re saying’.”

Their most recent track, ‘Acid’ – released last month – encapsulates their idiosyncratic style. Ellery’s luscious singing makes for a typically lovelorn track, while Skye’s production and melding of different genres, embodied by the inclusion of both violins and synths, is in full force.

Going forward with his personal endeavours, which has already heralded a sumptuous seven-track album, Kode Fine & Sons, Skye is looking to elevate the musical-theatre aspect of his sound, bringing it into more contact with electronic music, in a swirling sonic success.

I want to do something really melodramatic in that musical-theatre style but not have it as a pastiche of musical theatre, but have it as electronic music

These genres may seem worlds apart, but Skye’s experiences – growing up, being on tour and his continual development at Guildhall – make him a prism through which they’ve harmonised.

“I really like the showtune thing. That’s something I want to do; I’m going to try and do that eventually. I want to do something really melodramatic in that musical-theatre style but not have it as a pastiche of musical theatre, but have it as electronic music.”

Certainly, there’s already a storytelling element to his lyricism, though he admits not to strive for a deep, poetic meaning with his tracks. “I don’t really know what my songs are about,” he says, as I feel Lord Tennyson’s poetry, among others, heating up on the bookcase, “I don’t think anyone really knows what their own songs are about.”

“It’s difficult when you release something and then you have to write a press release saying ‘this is what it’s about’ ’cause I think the best things I write, it’s like something’s doing it for me. I don’t really know what’s happening.”

I don’t really know what my songs are about, I don’t think anyone really knows what their own songs are about

“The songs that were most successful are not necessarily about a broken heart – they’re the songs I feel I had the least to do with. When I write lyrics, I never have an intention that I need to write about something. I just go to the mic and see what happens. And sometimes it makes sense, like it’s a story.”

“It’s difficult when you write music with lyrics though, because suddenly there’s a hierarchy and the lyrics are at the top and then whatever the song means is defined by them. And I don’t think that’s the case – you have to look at everything equally, especially with the mix.”

“What I really like about a JPEGMafia album is,” he says, his sunlit tour with Injury Reserve evidently rubbing off, “his mixes are just as emotional as the music. The way his mixes are pumping or stopping, starting or elasticating – it feels like they’re moving themselves, it’s not like he’s just done it so the kick and the snare is loud enough, the vocal is loud enough, you can hear the chords. Things are fighting to be heard.”

“So for me, the lyrics are just an aspect of an object where everything’s equal – including how it’s mixed. But I don’t think that’s how people want to view it ’cause they want to know what the songs about and what they get from it. If you look at Bob Dylan’s lyrics, sometimes they make complete sense, sometimes they make no sense. But that doesn’t make the ones that make no sense any less meaningful.”

Look at Bob Dylan’s lyrics – sometimes they make complete sense, sometimes they make no sense.

In full flow, Skye reveals his inner artistry. Now in his final year at Guildhall, among other fledgling acts, including a hearty chunk of the Black Country, New Road clan, Ethan P. Flynn and, not to mention, Skye’s own Jockstrap accomplice, Ellery, Skye is solidifying his own talent.

Question is, does he feel like an artist? “I think I have over the past six months,” he describes, “I just don’t stop thinking about it every second of the day. And I have to do things to stop thinking about it.”

“I meditate, every day. For four years now I’ve been going to the Buddhist Centre in Bethnal Green. It’s not a religion, it’s not like a set of rules, it’s like a set of questions, which to me are really interesting just to think about.”

“My Dad’s a Buddhist – so there’s always been that. I had a weird mental situation where for about three weeks, I just felt extremely anxious. It was something I just didn’t understand. And then as soon as I felt that, it was so horrible that I just made a decision not to continue ignoring any mental-health strategies.”

I meditate, every day. For four years now I’ve been going to the Buddhist Centre in Bethnal Green.

“It just made think, ‘look, I can’t ignore my brain. I need to do something to nurture it.’ So from then onwards, it was a no-brainer,” or perhaps a yes-brainer, “that I needed to invest in something. And then it just made more and more sense the more I got into it.”

“Has it affected your music?” I enquire. “I think it’s just affected my life. I think what you do in your life affects your music. But I never really want to write about Buddhism.” Now, there’s a thought, right, Tennyson?