In this time of self-imposed ostracism for the good of the realm, having ‘projects’ becomes less of an afterthought, and more of a requirement.

I’m still hoping to watch the more than three hundred films on Roger Ebert’s Great Movies list. Like last week, four Great Movies, and one not-Great-Movie-but-great-movie – but only in order to keep sane.

This week, though, they are all films produced and shot in Britain, by British directors.

Monday

ArrayMeantime, Mike Leigh, 1983

I think we all know the feeling of discovering something great and wanting to hang onto it for just a little while longer before sharing it. The most likely domain for this to happen is usually music – there are countless variations on finding some forgotten old album, realising its value, and keeping it to yourself until the time is right for it to be dispersed. There’s an element of egoism (especially since you are NEVER the first to have heard it), an element of pride, and mostly, an element of delusion – since either way, what you have grafted from the film or album is entirely different from what the next man, woman or dog along has.

Apart from The Moment of Truth, this film is the first in this journey that I’ve felt this way with.

As usual – I won’t bore you with too many details of the story – as there isn’t really any, but it largely follows two brothers in one of those classic sibling relationships where bullying and deep care are separated by almost indistinguishable lines.

As the brothers (Phil Daniels and Tim Roth) grow increasingly disaffected, Leigh punctuates the grinding boredom of their daily existence with tense encounters, including with a priggish aunt who has ‘climbed’ to become middle-class and now possesses a paternalistic, nanny state instinct to ‘help’ her extended family back on the estates.

The dialogue feels a lot like Beckett, often meandering or taking its time to find the point of the sentence. If the mood were a little less sombre, we could imagine these to be word games, like the verbal jousting of Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. It’s described as a comedy – and there are funny scenes, but the humour comes more as momentary respite from all the rest of the shit.

The surprise of the film was a blithering skinhead on the verge of psychosis – played by an incredible, scene-stealing Gary Oldman, in his first major role.

Tuesday

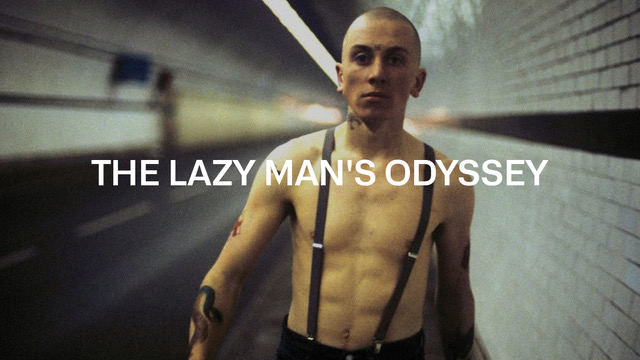

Made in Britain, Alan Clarke, 1982

It was a great coincidence and blessing that I watched these two films on consecutive days. Both starring Tim Roth, albeit in shockingly different characters, they both deal with the dead endness of Thatcher’s Britain for so many. There is no future, little past for these young characters to yearn back to, and therefore the present is the only respite. The present becomes the only thing left to do is destroy in random acts of nihilistic vandalism.

This film unfolds like a play – in only a couple of locations and a limited cast. But the walk-and-talk energy of the protagonists, and the quick movements of the camera make it more cinematic than films with thousands of times more budget.

Roth’s character in Made in Britain has all the typical skinhead characteristics – it’s not even subtle. Skin shaved hair, swastika on the face, doc martens and white vests – but he spends most of the film with his Caribbean roommate, Errol – seemingly unaware of the hypocrisy of his position. Its reminiscent of a Louis Theroux episode where he visits a leading Neo-Nazi in the depths of the Midwestern US, and as the episode unfolds, we realise this man’s private vicious tirades against non-whites is in opposition to his apparent friendship with South Americans and others.

Errol, who, noting Trevor’s overbearing charisma, begins to act like a sheep, following him around, parroting Trevor’s racist language when targeting the home of an Asian family late at night – ‘Baboons, go back to the jungle!’ – from a young black boy, is perhaps the release he gets from trying to ‘belong’ in some strange way.

There is an exceptional scene in the middle of the film where Geoffrey Hutchings cannily calls on a blackboard in a locked room of the assessment centre every move in Trevor’s life – past and present – like a snakes and ladders game where the last square is always prison.

In a time where the skinhead stereotype was that of mindless thugs, Made In Britain is a sobering dissection of the truth.

Alan Clarke’s trademark use of Steadicam began with Made in Britain (actually one of the first uses of the rig for TV) allowing him to capture every spurt of energy the wild Trevor – who barely keeps still across the full 70 minutes.

My Beautiful Laundrette, Stephen Frears, 1985

The nice thing about this film is that, much as it takes a place among the ranks of the great queer dramas, it’s never really made into the main point. The sexual relationship between Omar (Gordon Warnecke) and Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis) is relatively important, but takes place in the wings, leaving the centre stage for a multi-charactered, -faceted, and -cultured story. Their scenes of passion are confined to lowkey meetings – their love much better conveyed with stolen glances, calculated smiles, and (for the time) dangerous physicality.

It is a portrait of Britain at its uncomfortable multicultural zenith – the first waves of migration were more than over and hard working immigrant families (as well as wealthy immigrant families back in their mother country – this is an important distinction the film makes) have started carving strong places for themselves within society. Daniel Day-Lewis, in one of his earliest roles, plays a disillusioned cockney youth, who somehow manages to reunite his love for a brown person, even more scandalous, a brown man, with his outdated belief system. His skill, though, is apparent in his depth. Half the character is a composite of Gary Oldman’s character in Meantime and Tim Roth in Made in Britain, and half is a sensitive, delicate presence who charms his way into the protected ranks of the large extended Pakistani family.

It is telling that the second-generation immigrant in the film has many more options than his white British counterpart, although most of those options remain working for various family members in their various legitimate and semi-legitimate businesses.

It touches on so many things this film, xenophobia, sex, alcohol, witchcraft, family, but if one word really comes to mind, it is compassion. It treats all its subjects equally, without judgement, and without deceit. The alcoholic father, the dodgy uncle, the randy cousin – though I’ve just reduced them to gaudy adjectives – that’s the opposite of what Frears does.

The other thing we get is a true sense of place. I’ve yet to see London portrayed truly well on film – though the recent gangland TV dramas set here give you a good perspective of the underworld. All too often I think you know when a director doesn’t actually live in a place he is filming in (unlike how you feel the Safdie Brothers know New York intimately), and all too often London is shot by people interested in the Westminster skyline and nothing else. My Beautiful Laundrette mostly takes place on a typical Lambeth street, one where as residents of this strange town, we recognise the unwavering offie, the drycleaners, the pub, the ethnicities, the dress, the narrow streets. It is a film that knows its subjects.

Thursday

Passport to Pimlico, Henry Cornelius, 1949

It’s funny and fitting that one of the great Ealing Studios films (for a long time the top dogs of British cinema) is about the French. The film vignettes into the realisation that Pimlico, in central London, had been bequeathed centuries before to the people of Burgundy, in France, leading to the Pimlico residents to create their own Burgundian micro-state in the middle of London.

Late one night, the Burgundians covertly connect a hose to a nearby British water main, which fills a bomb crater, solving the water problem. The Burgundians are locked down by the angry government, until sympathetic Londoners begin to throw food parcels across the barrier, and soon others join in; the Burgundians have an ample supply, and decide to stay. A helicopter pumps milk through a hose and pigs are parachuted into the area.

The film studies scholar Charles Barr, in his examination of the Ealing Studios films, observed that in opposing the British government, the Burgundians ‘recover the spirit, the resilience and local autonomy and unity of wartime London’ – suggesting the actions ‘re-enact, … in miniature, the war experience of Britain itself’. Film historians Anthony Aldgate and Jeffrey Richards describe Passport to Pimlico as a progressive comedy because it upsets the established social order to promote the well-being of a community.

It’s a rare film that ably balances pure comedy with a slightly more complex side, in this case, a sort of yearning nostalgia for the social unity of the war years.

Friday (non-Great)

Kind Hearts and Coronets, Robert Hamer, 1949

With Meantime, Made in Britain, and … Laundrette, coming from such a similar time, it only made sense to go with a contemporary of Passport to Pimlico for the Friday. Released in the same year, Kind Hearts and Coronets has remained a classic of British cinema. Intrigue, murder, family plots – it has it all. The issue with these Ealing comedies is they don’t lend themselves too well to comments – since they are mostly light comedies for a traumatised post-war public. Nuff said.

Further thoughts:

- I spoke only of compassion in the notes on My Beautiful Laundrette, but if there’s one constant that pierces through these five films, it’s exactly that. In this – albeit limited – microcosm, British cinema becomes an exercise in treating characters and subjects fairly and with distance. Trevor from Made in Britain is an entirely unique depiction of such a character. Television all too often takes the easy route of the cliche – but these films tell viewers in their cosy homes just what the real world is actually like – a complex and confusing thing indeed.

- Easy to say, but British actors have a versatility that not many other countries’ actors do. (Think of Samuel L. Jackson getting pissed at Daniel Kaluuya for ‘stealing’ young Americans’ roles.) Gary Oldman in Meantime is unrecognisable; a terrifying, charming, sociopathic character. Daniel Day-Lewis – in one year (1985) plays this queer, bleached haired, possibly Fascist man (…Laundrette) , and then the poshest, most Daedalian and ridiculous dandy in A Room With A View. That’s versatility.

Next week, we’ll take a look at Casino (Martin Scorsese) and Babel (Alejandro G. Inarritu), among others.