Like last week, four Great Movies, and one not-Great-Movie-but-great-movie – but only in order to keep sane.

A few months ago, critic Sophie Mayer analysed Criterion’s entire collection and found that only 21 of their titles were directed by women. That’s 2.6% of the whole collection, which in Mayer’s estimation, is a ‘pretty meagre number’.

I haven’t even managed to find five women directors on this bloody list, so here are five films… with female protagonists.

Monday

ArrayThe Piano, dir. Jane Campion, 1993

Something I’ve realised through these weeks is that watching a two hour film is essentially abdicating your worldview, and allowing someone who you don’t know to lecture you on his or her vision of humankind and the planet. This is much more the case with ‘cinema’, than our typical big studio drivel.

This is a film that dunks your dainty little head into cold mud so deep you could drown in it, and doesn’t let you get a breath till you accept – at least a part of – her vision.

The most obvious device in this film is the selective – though selective doesn’t do it justice, more elective – mutism of the leading lady. After that, everything is as murky as the world they inhabit. It is set on an early colonial settlement on the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand (specifically the Karekare Beach). The landscape around them, and Ada’s lack of speech is the purity and honesty of the film.

Campion often speaks of the influence that New Zealand and being a New Zealander has had on her. Noting the Puritan side of the colonists, she talks about her curiosity about who her ancestors were, and how New Zealand must have been a very puritanical society for them, especially as far as the repression of sexuality was concerned.

The beauty of landscape furnishes symbols capable of conveying lingering unconscious effects. She describes the New Zealand bush as ‘claustrophobic, impenetrable … like swimming underwater’.

In the community also lives Harvey Keitel’s character, Baines. He is a white man, but has taken up the customs of the local Māori, such as tattooing his face, speaking their language, and protecting their land. As he has come to live there his faculties of communication have grown and flourished. The natives have nicknames for him and they have heartfelt conversations about his life and desires.

This aspect is never explored in too much detail. It does not become a film that examines the first bad or dishonest moves in terms of the settling of New Zealand. Baines falls for Ada, and in order for her to regain her beloved piano from him she will give him lessons. There are 88 keys, so 88 moments together. But then he gives her one for taking off her jacket. Five for raising her skirt. But Campion, who wrote and directed, does not handle this situation as a man might. She understands far better the eroticism of slowness and restraint, and the power that Ada gains by pretending to care nothing for Baines. The outcome of her story is much more subtle and surprising than Baines’ crude original offer might predict.

There is a beautiful scene where the natives react badly to a performance of ‘Bluebeard and his Wives’. This is a little wink at the audience – for the film serves as an eventual retelling of Bluebeard.

To me, the end feels a little like a cop-out. I won’t spoil it but essentially by an easy narrative technique Campion manages to wangle two endings out of one film. It seems a little like one is too depressing to end on, the other not powerful enough – so they went for both. A bit like the Parasite ending.

Tuesday

Cléo from 5 to 7, dir. Agnès Varda, 1962

It is tricky enough to play a sprite who skips lightly through life, but how in doing that do you also communicate an intense awareness of mortality? Cléo from 5 to 7 follows the two hours in Cleo’s life as she awaits a meeting with a doctor – and possible cancer. She is young, beautiful, sophisticated, but also deeply unstable.

The film opens in colour, on a top down shot of a tarot deck. Otherwise it’s in black and white, but this three minute introductory colour tarot reading sets the tone for the intensity that’s to come. We are not Tarot readers, but they look alarming to us. The Hanged Man and Death make their ominous appearances, and the Tarot reader reassures Cléo, as such readers always do, that the cards ‘can mean many things.’ Later, when Cléo asks for her palm to be read, the reader looks at it and says, ‘I don’t read palms.’ Not a good sign. Cléo seems a shallow enough woman that these portents depress her.

Just about the only original thing I have to say about this film is the untruth in the title. The film, actually ninety minutes, ends at 6.30, rather than 7. Is it after the entrance of young soldier Antoine into her life, where her typical linear relationships are entirely questioned, and as she becomes intensely connected to this man within fifteen live minutes, that time simply does not matter any longer? Would you keep to a family dinner at 7 if you met the love of your life half an hour before? Probably not.

After meeting Antoine, they speak, they walk, they travel by bus, then walk again. Observe with what enormous tact and restraint he speaks to her. He doesn’t know of her day’s health worries, but he has worries of his own, and Varda’s dialogue allows an emotional bridge to exist between them. Then Cleo is told her test results with almost cruel informality by her doctor. Then she and the soldier talk a little more. If you want to consider the differences between men and women, consider that what Antoine says here was written by a woman, and that many men would have found it out of reach.

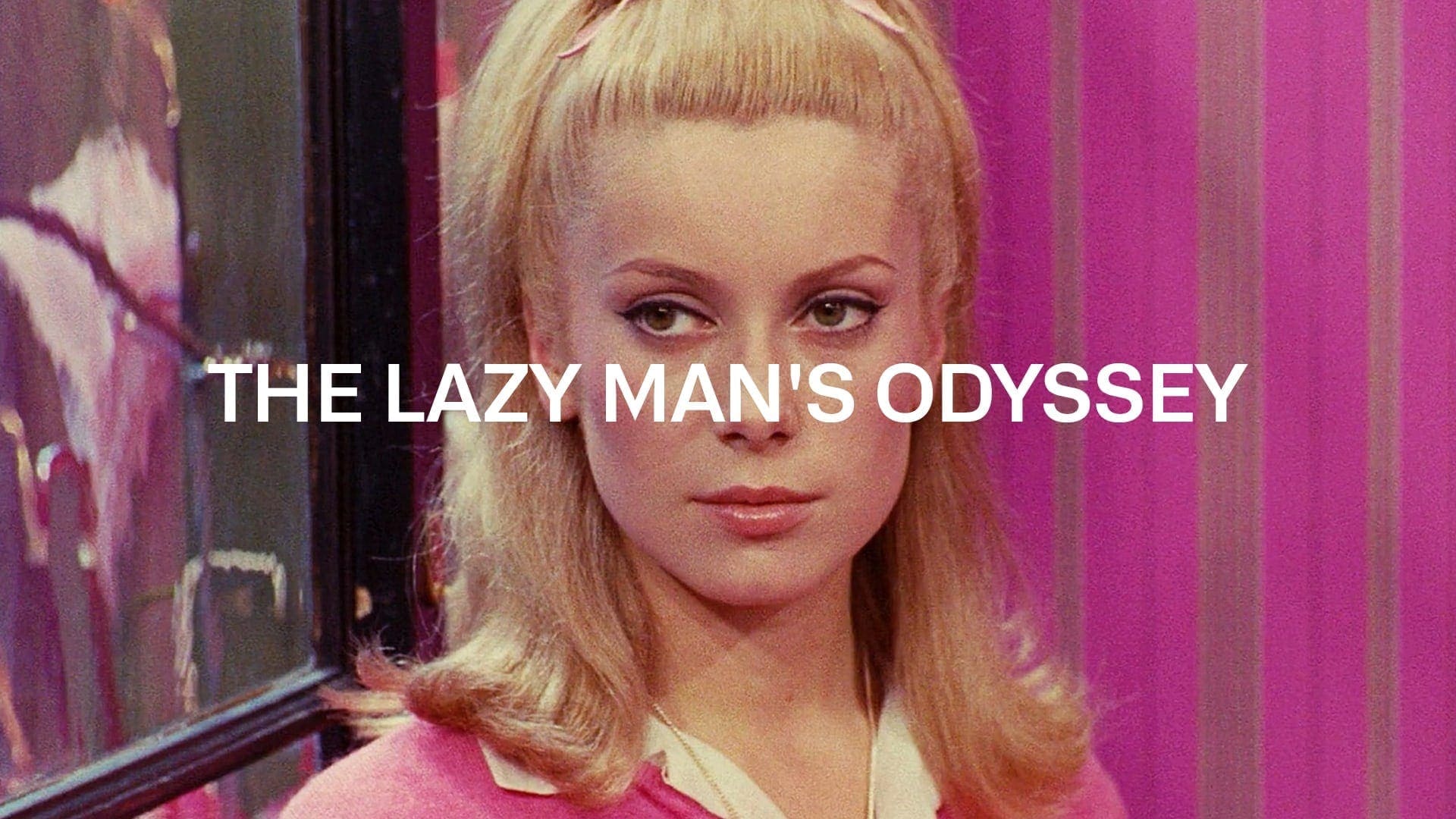

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, dir. Jacques Demy, 1964

So we only got to Wednesday and already have to cheat by choosing films about women, rather than by women. Jacques Demy was Agnes Varda’s beloved husband, the film I watched yesterday.

The film is divided into three parts named ‘The Departure’, ‘The Absence’, and ‘The Return’, spanning November 1957 to December 1963, and is also part of a wider trilogy of shared themes and occasional shared characters.

Since it is entirely sung through, there were none of the usual constraints of having to find dub singing voices similar to that of the actors. That gave great liberties to Demy and Michel Legrand in the voices of singers – who would record the soundtrack before the shoot started. They wanted to avoid the operatic side of singing, so needed to find simple voices that went with the text and the music. They need ‘jazz people’ – because of all the rhythmic moments, the quick pace changes, and difficult note sequences.

There is a Janus reading of Deneuve’s character. One one side, she is a young girl, in love, innocent and blind to the pains of distance. Her inability to choose is perceptible from the beginning of the film where she knows not how to respond to the barman asking for her order (‘a squeezed … thing, please’), to the end of the film where the petrol boy asks her what fuel to put in her car, and she shrugs him off.

The other hand, though, reveals that Geneviève’s ‘betrayal’ is due to her world. First off, her melancholia is telling. Though she is young, she is world-weary – certainly not immature. When she realises she is pregnant – 1958 in the film – young mothers were still not allowed to get the ‘livret de famille’ – or documents certifying that single mother and child were a ‘family’. Her mother gives her no sex education under the pretext that when she married her father she knew none either. It is, I think, social pressure, much more than a lack of willingness, that would explain Geneviève’s procrastinations.

Deneuve looks at the camera twice in the film, a stare meant for the public. When she chooses her wedding dress she looks at us momentarily, before a stark cut transposes her to the church, in the process of marriage. It’s a scary fucking look. Her look is an accusation against all of this anaesthetised France that would make her life impossible if she rebelled.

It is a film about a girl who accepts to bend her dream to the constraints of reality.

Thursday

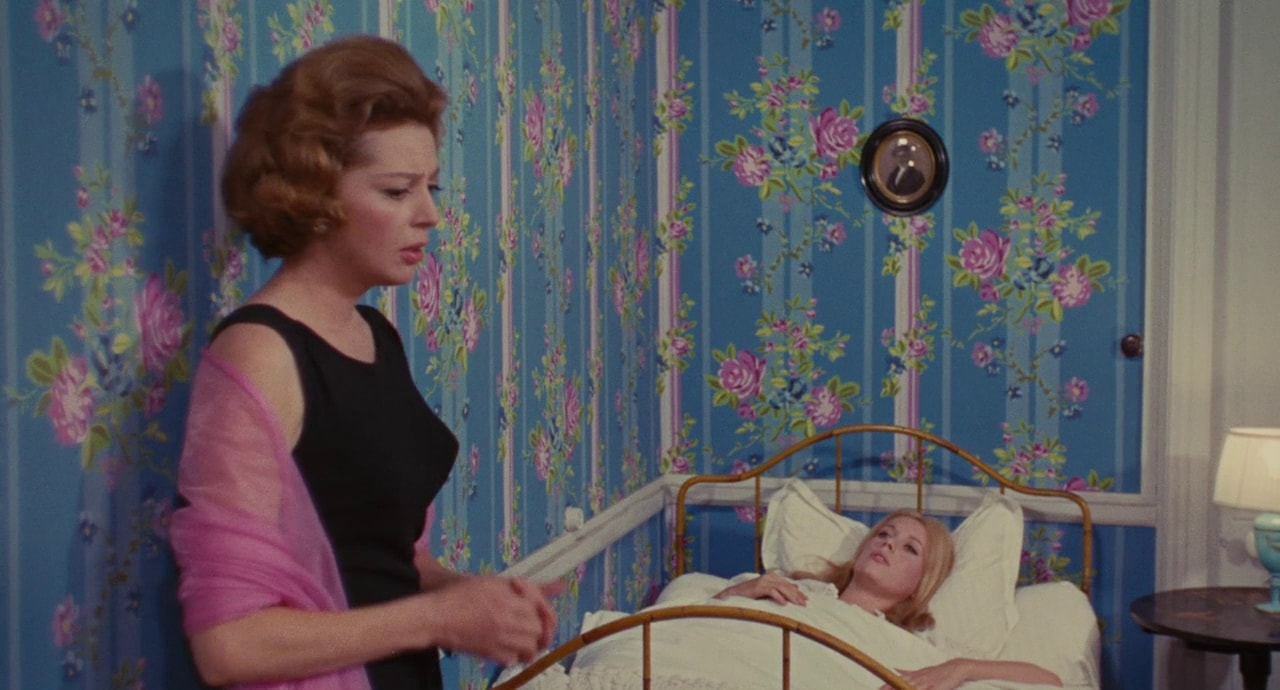

Belle de Jour, dir. Luis Buñuel, 1967

I’m not sure whether this film is supposed to celebrate the liberation of the woman or is more of a man’s twisted vision of how he thinks women in sexless marriages feel. This film stars Catherine Deneuve, three years on from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and you can’t help feeling like the showbiz world has forced this particular woman to grow up too quickly. In The Umbrellas she is basically a girl, in a complex love story. In this, she is more in control, more mature, but also, much, much, more sad. Deneuve is an actress who raises a feeling of melancholia even when bent over backwards laughing – there is a strange sensitivity to the agonies of the universe.

Deneuve plays an upper middle class Parisian woman, married to a man she loves but is not aroused by. We sometimes enter into her fantasies (though the fantasy is carefully never too far from real life), where she dreams of being humiliated and hurt by the men in her life. She becomes a high end prostitute in the weekday afternoons, caring for a menagerie of customers in an innocent Paris flat.

With some white lingerie reminiscent of intricate ecclesiastical vestments, she starts enjoying this double life. The customers don’t just want sex – they want the fantasy of being popular, of being attractive, of being the life and soul of some imaginary afternoon party as they incessantly call for champagne that is invariably too warm. Some want masochistic roleplay fantasies. It is fantastically shot, using constant subversion as a battle tactic. After a particularly intense session with a large man and his (unseen, but electronically buzzing) ‘toy’, we regroup with Belle with her face down, corpse-like and still. We imagine the worst has happened. As she lifts her head, though, we realise she is still riding the wave of post sex elation.

One grand gentleman, a distinguished gynaecologist, wants to be humiliated (to today’s sensibilities the scene plays as entirely comic). He asks her to play the ‘Duchess’, he hesitates between being the butler, or the driver. We can imagine the discomfort of a 60s screening room as this man sends her out for another more experienced comfort woman who knows how to treat him, well, badly?

Here is the bizarre pantomime of sex, from which the director often subtracts the eroticism. Séverine’s hoodlum client Marcel (Pierre Clémenti) looks at her off-camera naked body and weirdly murmurs: ‘Shame you only have two of them…’

Friday (non-Great)

Persepolis, dir. Marjane Satrapi, 2007

An animated film set in Tehran before, during, and after the Iranian revolution.

The film is presented in the black-and-white style of the original graphic novels. Satrapi explains that this was so the place and the characters would not look like foreigners in a foreign country but simply people in a country to show how easily a country can become like Iran. The present-day scenes are shown in colour, while sections of the historic narrative resemble a shadow theatre show.

Despite its simplicity, the animation team mentioned how black and white makes imperfections even more obvious: ‘Using only black and white in an animation movie requires a great deal of discipline. From a technical point of view, you can’t make any mistakes…it shows up straight away on the large screen’.

The team also worked on techniques that mimicked the styles of Japanese cartoonists, known as manga, and translated them into their own craft of ‘a specific style, both realistic and mature. No bluffing, no tricks, nothing overcooked’.

You can tell that it is a genuine passion project. It’s a film that seems like everyone working on it would have enjoyed themselves – despite the subject matter. Imagine working on a film that is a true

story, where the protagonist of this story is leading your crew, and where the film is an animated movie that deals with important current issues for adults.

Next week, we’ll take a look at Shadows (John Cassavettes) and Shaft (John Singleton), among others.