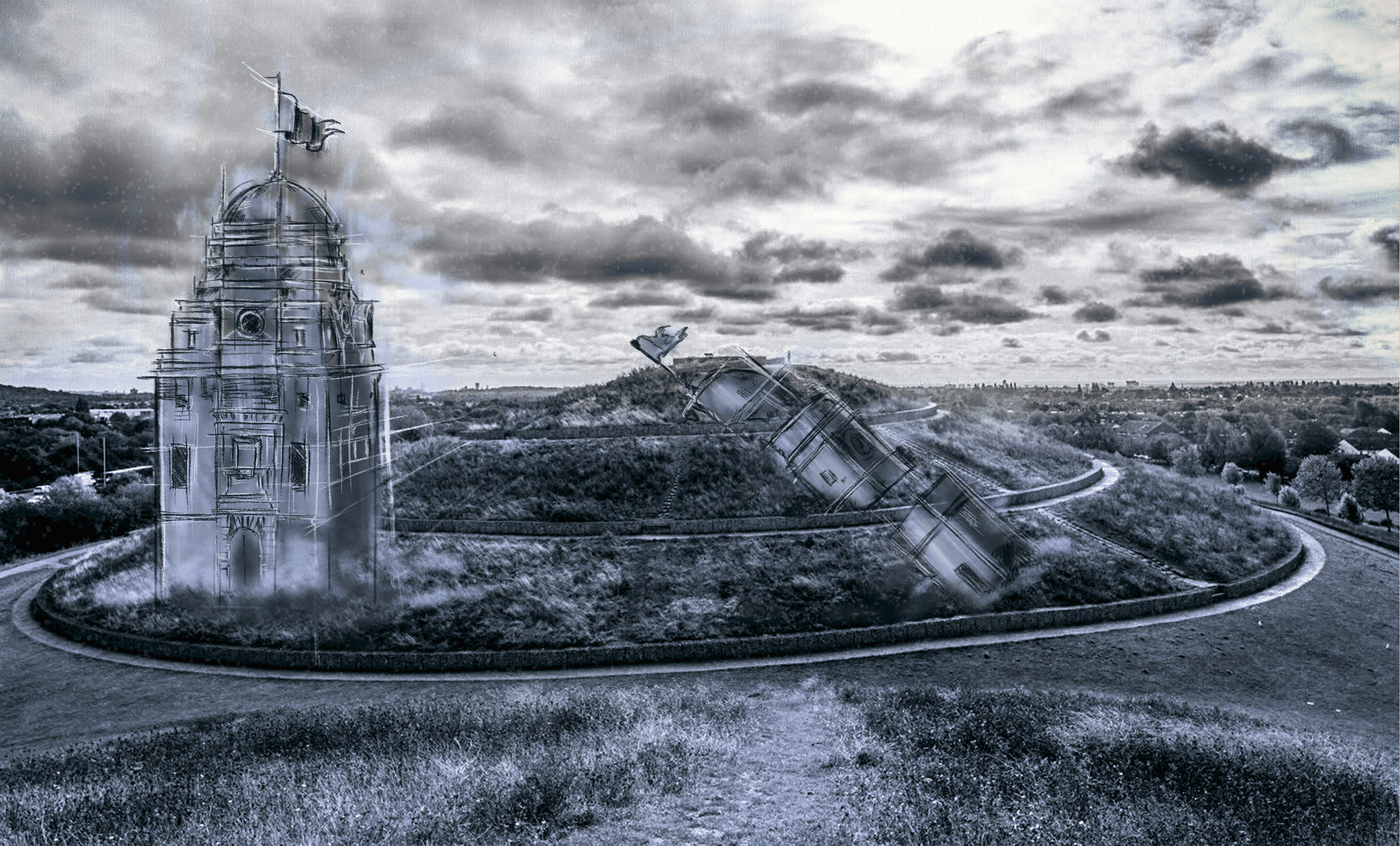

Demolished in 2003, the old Wembley Stadium now lies in the artificial mounds at Northala Fields. Percy Preston visits the grounds in homage to one of football’s sacred yet forgotten sites…

Old Wembley’s towers were buried beneath giant mounds of earth after demolition – the site is unmarked in Northala Fields, West London

The Westway is an unlikely road for a pilgrim. But I am on a pilgrimage – even if the highway and its surroundings seem like they were built to purposefully deny the possibility of spiritual renewal. A scar of botched mid-century surgery, the road was meant to relieve congestion leaving London’s West End, but has caused graver complications of its own, suffocating the adjacent neighbourhoods with fumes and noise.

Ascending to the Westway from Edgware Road, another monument to twentieth-century confidence dominates the skyline. Designed to bring future living to the present, yet looking like a brutalist headstone, Trellick Tower now serves as a warning against the utopian optimism of the past. Some say that Trellick inspired J.G. Ballard’s dystopian novel High Rise, which tracks the descent of residents, who occupy a luxury tower block, into mass psychosis, savagery and extinction.

Designed to bring future living to the present, yet looking like a brutalist headstone, Trellick Tower now serves as a warning against the utopian optimism of the past

Heading beyond Ladbroke Grove and Shepherd’s Bush into low-rise Acton, subtler indications of mortality exist for those who look carefully. A doctor’s practise advertises itself with olde English gothic script reading ‘Surgery’. It’s an unlikely sales ploy. A visit from a Tudor doctor was more likely to cause death than prevent it. Further west, Northolt – the destination for my pilgramage – is famous for another death. It’s where Princess Diana’s body was flown after her fatal car crash in Paris.

I hadn’t, however, come to Northolt to pay my respects to the People’s Princess. My visit was to the resting place of another departed icon. The remains of the old Wembley Stadium lie buried in an unassuming park next to the A40 called Northala Fields. Some burial sites are all about remembering, but this stretch of land passing through Northolt is where you’d bury to forget. Traffic passes, but few people stop. Proximity to a major road guarantees a large, but inattentive audience.

Some burial sites are all about remembering, but this stretch of land passing through Northolt is where you’d bury to forget

The rubble collected from the demolition of Wembley’s towers forms four large hills, resembling Saxon burial mounds or barrows. Each is covered in grass and wildflowers with a gravel path engraved in the side that circles its way to the top. Much like Saxon sites, there is little adorning the hills and almost nothing to suggest that a great national institution lies here.

That lack of commemoration is unusual – especially today, in our age of non-stop memorialising. At a time when attention spans are shrinking and forgetting ever more easily, we compensate by erecting a slab to anything and everything that once was. While London chucks out the old with the same abandon that it always has, we also now systematically sustain the memory of the things we destroy. This is especially true for football in the city. There’s growing nostalgia for an earthier, less monied game. But at the elite level that fondly and probably mis-remembered version of the sport has largely evaporated, shrouded in the dust of London’s iconic stadiums. In the past thirteen years, Highbury, the Boleyn Ground and White Hart Lane have all been knocked down.

That lack of commemoration is unusual – especially today, in our age of non-stop memorialising

London’s major clubs excel at making token gestures to a heritage they themselves erased. The facades of Highbury’s East and West Stands have been preserved as the shell of (luxury) apartments; the dent that Gazza allegedly put in the Cockerel that crowned the old White Hart Lane has been carefully imitated in Tottenham’s new stadium.

But Northala Fields is different. The focus here is as much on breeding new life, as it is commemorating the past. Stadiums retain their clamorous devotion on the inside. Today, the old Wembley’s remains shield the park and its wildlife from the spectacle and noise of the A40, making it a sanctuary for a different kind of devotion: that of the pilgrim, quietly paying their respects, (or in the case of one young couple, for another kind of devotion: a clumsy al fresco snog).

Standing at the top of the tallest mound, you can vaguely make out the arch of the new Wembley in the distance. Looking down the other way, children are playing a game of football at the bottom of the slope. I wonder if they know on whose remains their kickabout is taking place? Perhaps it doesn’t matter. The image conjures a satisfying circularity. The doyen of football stadiums is at peace – he has come home.

Percy Preston is a freelancer writer and founder and editor of Midfield Generalities. He lives in South London.

2 Comments

Hello, Percy thank you for this description of what happened to the old Wembley stadium. I grew up in Lyon Park Ave, Wembley and as a child if I stood up on the sill of our back bedroom windows would gaze at the twin towers in the distant. Thanks for this homage to an icon. Max.

I worked for a company that supplied building materials for the new Wembley stadium. While I was waiting in the centre of the stadium, before the pitch was laid, I got in to a conversation with a man who worked for Multiplex, the general contractors. During our chat, he excused himself & said that he would be back in 5 minutes. True to his word he returned and was holding a lump of concrete in his hands… and yes it was a piece of the twin towers. He said that it is identifiable by the ridges on the outer surface of the towers of which this has. It also has a light beige painted surface, which from memory I think were the bases of the structure, but I could be wrong there.

It is still in my garden and has been used to stop the side entrance garage door from closing!