Boris’s Johnson’s address to the nation last Monday, in which he announced the biggest curb on civil liberties this country has ever seen, should have been one of those ‘where were you?’ moments. Except I’d imagine for most of us, the answer is obvious: we were at home, doing as we were told. ‘Telling my grandchildren’ about this moment may also present problems, as the likelihood of their existing recedes with every day isolation extends. Without the need to take any vows, I now live by the monastic tenets of chastity, poverty and obedience.

Confined to my house except for fifteen minutes of exercise every day, (I’ll be honest, I’ve skipped the exercise a few times) I escape via the books that I read. A pile of large hardback histories has stood for several months in my bedroom as a towering reminder of learning I would likely never possess. Quarantine presented the chance to purge the guilt of never having opened any of them.

A pile of large hardback histories has stood for several months in my bedroom as a towering reminder of learning I would likely never possess.

My exercise in literary self-flagellation began on Tuesday evening at eight o’clock with Diarmaid MacCulloch’s 600-page biography of Thomas Cromwell. It ended on Tuesday evening at ten past eight, with Diarmaid’s MacCulloch’s biography of Thomas Cromwell. I’ve no doubt it’s an admirable piece of scholarship, but four pages in and I was already overwhelmed by the number of characters called Thomas: Tudor parents were not the most imaginative name givers.

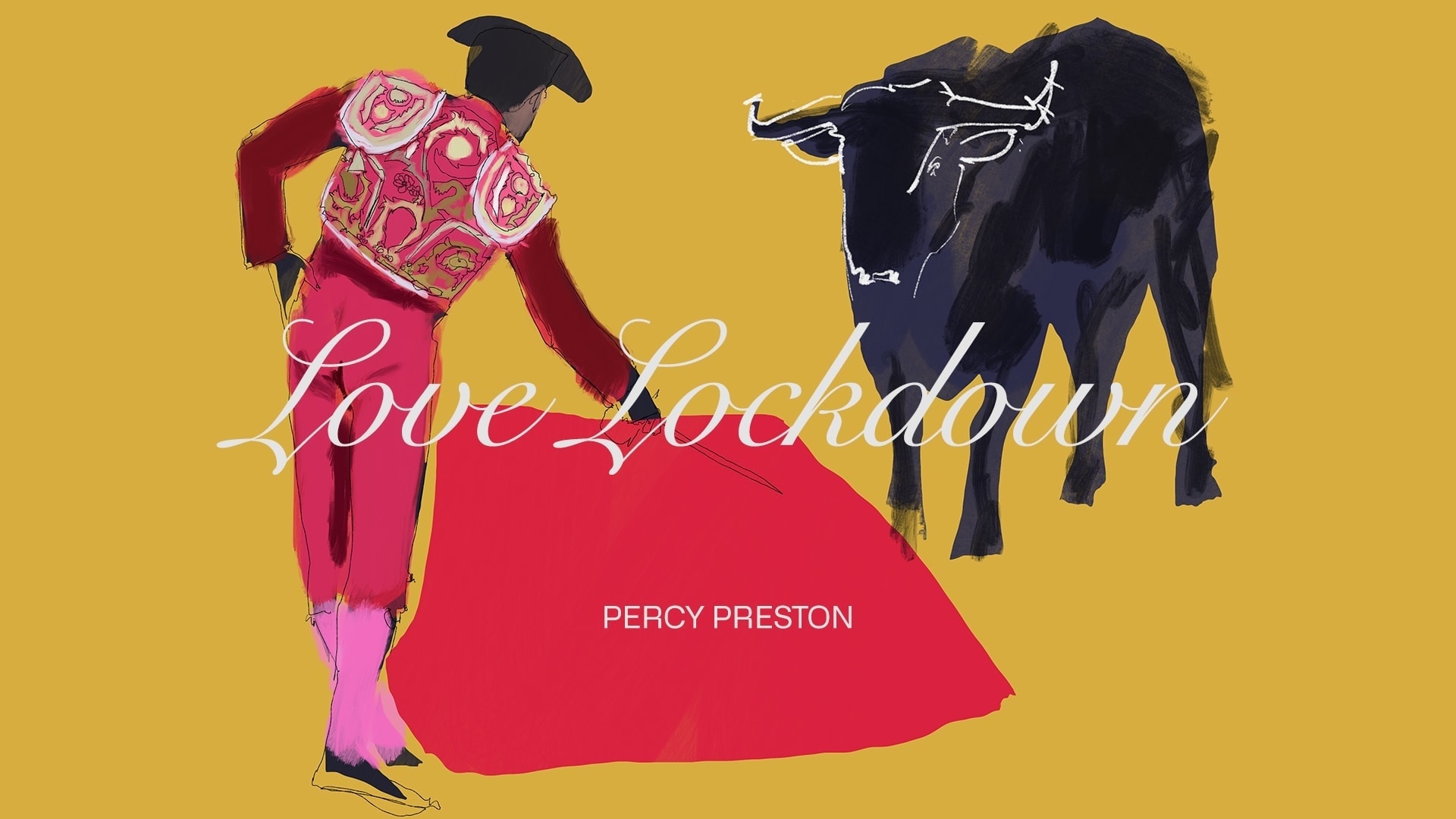

Instead, I turned to Ernest Hemingway’s book on bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon. Hemingway is a writer who intimidates you into liking him and his clipped, forceful sentences make reading him feel a bit like being punched in the face. His lack of ornamentation, he tells the reader, testifies to his honesty: he doesn’t hide behind florid writing.

Death in the Afternoon by Ernest Hemingway, 1932 first edition

And yet you sense that his forceful style can suffocate alternative perspectives: Hemingway, according to Hemingway, is absolutely right about everything. The directness of his style doesn’t allow much room for dissent.

Hemingway was certainly right about one, important thing. In A Moveable Feast, his memoir of his time spent in Paris as a young journalist, he records a conversation with his friend and fellow author F. Scott Fitzgerald, who was worried about the size of his penis. “You look at yourself from above” Hemingway told Fitzgerald, “and you look foreshortened.” In an anxious time, I hope that by passing this on, male readers will at least have one less anxiety to deal with.

I’m afraid Hemingway has rather less to say on how to cope with a pandemic. Though he lived through the Spanish Flu, it’s notable by its absence in his writing.

Without the consolation of that great author’s sagacity, you’ll have to make do with my admittedly anodyne observation that music can be a source of reassurance. I’ve been listening Brian Eno’s and John Cale’s collaboration song ‘Spinning Away’. The lyrics are ambiguous, teasing at meaning but remaining elusive:

“And there, as the world rolls round,

I draw, but the lines move round.

There, as the great wheels blaze

I draw, but my drawing fades.”

Hemingway would not have been impressed. But the song’s ambiguity lets the listener shape it to their circumstances. For me, the song speaks to the possibility of hope, even when things seem like they are spinning out of our control.