In speculative films and fiction, such as Blade Runner, The Truman Show and Infinite Jest, product placement is all around us, an insidious and inevitable part of the future we’re hurtling towards. But Sammi Gale investigates the origins of embedded marketing and finds that commercialisation got its tendrils into culture much earlier than we might like to think.

‘Contract or no, I will not bow to any sponsor.’ So says one Wayne Campbell, while posing with a delicious slice of Pizza Hut’s finest. The classic scene from Wayne’s World sees Mike Myers munching Doritos and chugging Pepsi, while Garth (Dana Carvey) reclines head to toe in Reebok. But are artists ‘selling out’ really as hypocritical as this skit suggests?

Ten years prior to Wayne’s World’s release, Coca Cola accelerated the practice of product placement as we know it today when the company bought Columbia Pictures for $750 million.

This move into the film industry made their rivals Pepsi a little nervous, and so they duly went to town plugging their own stuff in Back to the Future. For the sequel, they created a brand-new beverage ‘Pepsi Perfect’ that would exist in the fictional future. Product had become plot point.

Floodgates opened, BMW paid $3 million for James Bond to drive a Z3 in Goldeneye (1995), turning this initial investment into $24m worth of sales. Later Heineken would pay $45m for the spy to swap out his vodka Martini in Skyfall (2012). Harley-Davidson paid $10m to get its electric motorcycle into Avengers Age of Ultron (2015). More than 100 brands offered a combined $160m to feature in 2013’s Man of Steel.

While the soda wars of the 1980s might have accelerated matters, the relationship between cinema and product placement goes back a long way, and founder of the motion picture trade journal Harrison’s Reports P.S. Harrison was calling out the stealthy permeation of brands on our screens way before Mike Myers.

1920 saw the release of The Garage, a short film starring Buster Keaton and Roscoe Arbuckle. In several of the skits set in the eponymous garage, signs for ZEROLINE oils, as well as the Red Crown Gasoline logo, were prominently placed.

Harrison’s Reports took a stand: ‘The trade mark of that product appears in numerous scenes on the portable gasoline pump’, he wrote. ‘If Mr Arbuckle states it was an oversight, it would be well to caution him to avoid such oversights in the future.’ From 1921, the journal proclaimed itself FREE FROM THE INFLUENCE OF ADVERTISING and would remain unyieldingly against product placement in cinema until the end of its run in 1962.

Of course, product placement – and its protestors – predates classic Hollywood. In fact, it’s pretty much as old as film itself. The BFI’s digital collection cites Rudge Whitworth (1901) and Vionola Soap (1898) as early adherents, while even earlier films by the Lumière brothers featured Sunshine soap.

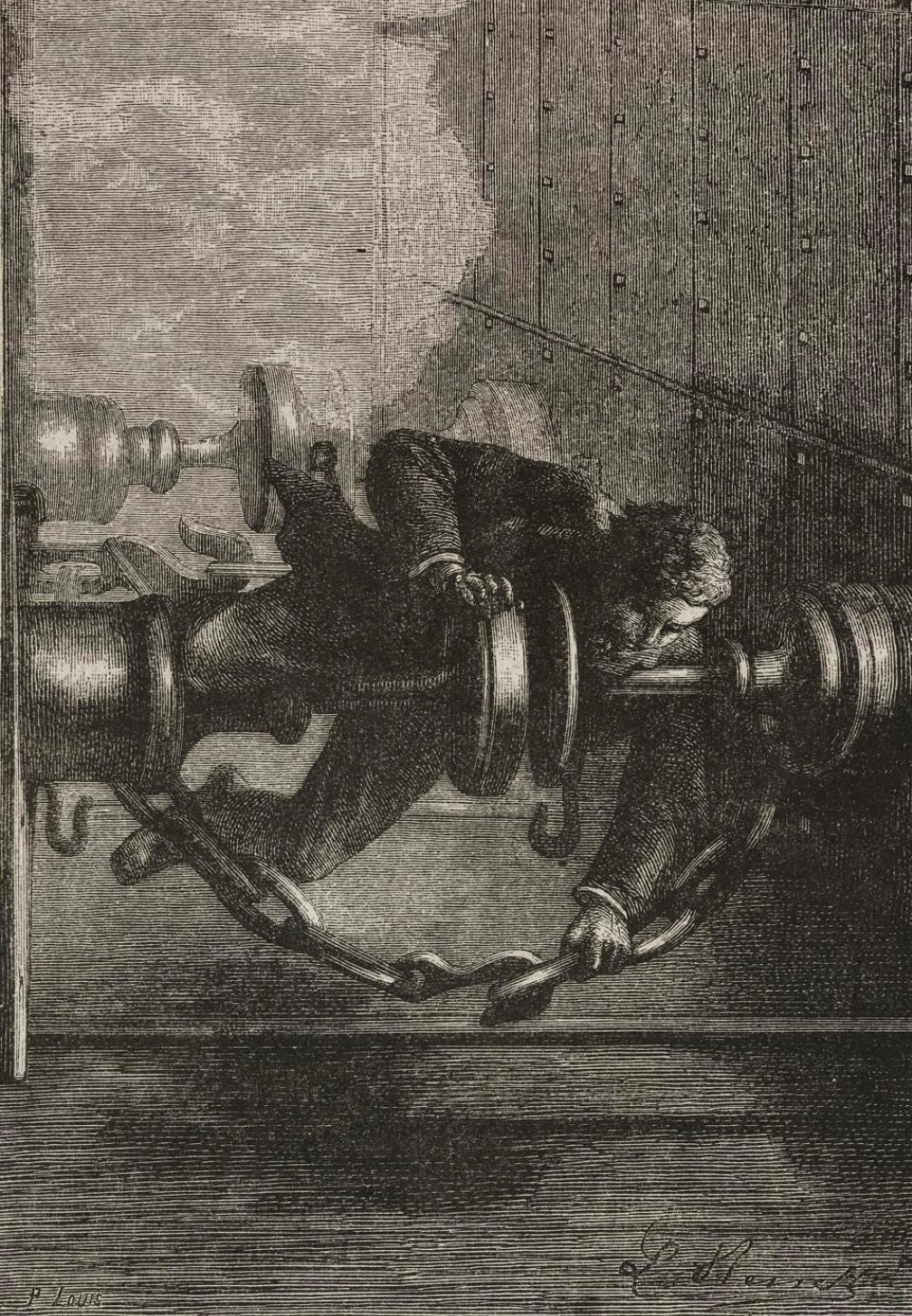

Gambalesta uncoupling the railway trains, from Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne

And pre-cinema? By the time Jules Verne wrote Around the World in 80s Days in 1873 he was famous enough to be lobbied by shipping firms seeking a mention in the book. Whether he was paid or not remains up for debate, but Verne certainly gave shout outs to real life transport companies.

The journalist Edmund Yates suggested that another famous Victorian novelist was similarly courted. In an 1883 column, Yates claimed that Thomas Holloway, of Holloway’s Pills and Ointments, ‘once enclosed a cheque for a thousand pounds in a letter to Charles Dickens, which he placed at Dickens’s disposal, on condition that one line of complimentary reference to Holloway’s cures’ was included in Dickens’ next book. The author reportedly sent the cheque back in the post.

ArrayIt wasn’t only literature that provided such lucrative opportunities. In Édouard Manet’s 1882 painting ‘A Bar at the Folies-Bergère’, the viewer is drawn in by a scrupulous barmaid who seems about to take our order. Immediately recognisable placed at either end of the counter are two bottles of Bass ale, with their distinctive shape and red triangle logo.

While there’s no definitive proof that Bass paid Manet to feature the brand in a painting that is, in any case, full of other, then-ultra-modern realist detail (including the electric light fittings that Folies-Bergère was early to adopt), Bass beer were certainly forward-thinking marketers. In fact, their red triangle logo design was the first registered trademark ever issued by the British government in 1876.

Manet’s reference to the brand – or Bass’ promotion in a Manet – is indicative of how marketing had become hugely influential in Victorian society. The purpose of the arts was expanding, as lithographic printing firms sprang up, tax on newspaper advertisements was removed and posters and hoardings became a part of the city scenery.

The line between high art and commercialism was blurred in unprecedented ways. Thomas J. Barratt – who was awarded a Guinness World Record in 2014 for being ‘the world’s first brand manager’ at A. & F. Pears from 1865 – acquired the copyright for John Everett Millais’ painting ‘Bubbles’ in 1886. As such, there wasn’t much Millais could do when Barratt added a bar of Pears soap in the foreground. The artist’s rather saccharine use of the bubble as a symbol for transience had become a marketing campaign; then as now, nothing lasts.

Barratt recognised the need for innovative ideas. ‘Tastes change, fashions change and the advertiser has to change with them,’ he said in 1907. ‘Not that the idea of today is always better than the older idea, but it is different – it hits the present taste.’ Why then has product placement remained so effective, even despite the best efforts of consumer groups such as Commercial Alert who object to the practise as ‘an affront to basic honesty’?

Well, perhaps precisely because ‘basic honesty’ is so highly prized in Western culture: advertisers know as well as artists that viewers crave authenticity. That doesn’t seem about to change any time soon.

As such, we are already seeing ‘the next natural step’ for product placement, in the words of Bhavit Chandrani, ITV, Director Digital and Creative Partnerships. This year’s Love Island saw ITV introduce ‘Shoppable TV’, which allows viewers to discover and buy products from its programmes directly on screen. Quite apart from decrying product placement, perhaps we should cut the pretence that what is on our screens is not for sale. Especially since it always has been.