A cowboy is being thrown from his horse. He clutches a canvas tight to his chest. Underneath is the caption: ‘Tom would never forget his first Mondrian.’ Another shows two soldiers staring out over no man’s land. The quote reads, ‘Permission to moisturize, sir?’

One more… Two Stuart men (ruffs and Van Dyke beards) crouch over a tiny disc illuminated by candlelight. Below their startled faces are the words: ‘It was the smallest pizza they had ever seen.’

These are three snapshots from the weird and wonderful world of Glen ‘Colonel’ Baxter – if you’ve been here before, you’ll require no further explanation. For more than 40 years, Baxter has combined gnomic word and ink drawing to create surreal comic vignette.

My own love affair with his work began aged 17 upon receiving a copy of his seminal collection, The Impending Gleam. It was like nothing I’d ever seen before. The drawings satirised the dash and derring-do depicted in children’s books of the 1920s and 30s, while the captions underneath contained sardonic non-sequiturs riven with literary reference.

The drawings satirised the dash and derring-do depicted in children’s books of the 1920s and 30s, while the captions underneath contained sardonic non-sequiturs riven with literary reference.

Baxterworld is a place populated by Rothko-loving detectives and paranoid existentialist cricketers. Despite, or perhaps because of, its vividness, the identity of its creator seemed inconsequential. So, to be sitting opposite him, in a pub in Kennington, feels perverse – like going for a pizza with Dr Seuss.

Shock-haired with a sergeant-major’s moustache, Baxter speaks with a Yorkshire accent undimmed by four decades of London life. As he explains, “I live in my head. I’m not really here.”

Baxterworld is a place populated by Rothko-loving detectives and paranoid existentialist cricketers.

With its pith helmets and elbow patches, his work has a fogeyish appeal. Today its followers can swap their favourite pieces using the powers of instant communication. Does the colonel know what a meme is? No. But Instagram has certainly helped spread the good word and ushered in a sort of demi-renaissance. Almost proto-memes, his drawings lend themselves to easy dissemination. They also offer a lacquered life raft among a sea of lol cats.

Baxter’s cartoonish surrealism seems so escapist, and I’m surprised when he dismisses the idea of ever leaving the hustle and bustle. “Oh no, I couldn’t live in the country. You know why? There’s no neon.” Of course – weaned on pulp fiction and cowboy B-movies, his art emits an incandescent glow.

This was a light source of inspiration lacking among his teachers and fellow students at Leeds School of Art in the early 1960s. They were intent on producing insipid abstract expressionism, but it was a different American school, the realism of Edward Hopper and George Bellows, that set the young Baxter’s heart racing.

A house in Leeds by the canal that looked just like Hopper’s House by the Railroad was “so melancholic, so cinematic. I used to stare at it for hours.” When he told his teacher this, he was dismissive, describing Hopper as a figurative artist, not worthy of consideration. “If that pillock was rubbishing it, I knew I was on the right track.”

Baxter’s cartoonish surrealism seems so escapist, and I’m surprised when he dismisses the idea of ever leaving the hustle and bustle.

And yet, by the time he left university, he had switched rails, rather ironically, to the surreal. “I thought the Surrealists and Dadaists were it. It was the humour really, it infected everything they did.” Baxter began dabbling in absurdist verse. He sent some of it across the Atlantic and was invited to read at the Poetry Project in St Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery: Beatnik Ground Zero. “People were laughing. I thought about moving to America, but my wife said… ‘maybe not’.”

Back in dreary old England, he turned once more, to the visual. It was while reacquainting himself with the collages of Max Ernst that he discovered the perfect foil for his own ideas of English Surrealism. “At a junk sale I found these old Boy’s Own drawings and thought, this is gold dust.” Baxter had found his universe.

Like Ernst’s source material – taken from steel engravings found in Paris flea markets – Baxter’s was cheap, plentiful and rather outmoded. “I started aping the style, which was so deadpan, and found that putting a fragment of a poem at the bottom meant I could create what the Surrealists called a frisson – something unexpected that didn’t fit the content and made you double-take.”

This revelation took place while he was teaching at Goldsmith’s – member of a radical faculty that included William Wentworth and Nicholas De Ville, and among whose students were a young Julian Opie, Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst.

I started aping the style, which was so deadpan, and found that putting a fragment of a poem at the bottom meant I could create what the Surrealists called a frisson – something unexpected that didn’t fit the content and made you double-take.

He had a series of postcards printed and took them to the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in a carrier bag. After some gentle nudging, they were persuaded to stock a few dozen. One showed a man holding a saw in one hand and his severed leg in the other, standing with two children above the caption: ‘Uncle Frank would keep us amused for hours.’ This ended up becoming the bestselling postcard the ICA had ever stocked.

A few months later, after an artist dropped out of an exhibition in the ‘concourse gallery’, they asked Baxter if he’d like to fill the space. The concourse turned out to be a corridor between the bar and the toilet. He jumped at the opportunity to have his work “seen over and over by the same incontinent person”. There must’ve been a few weak bladders in that night, because the show was picked up in The Times and the Guardian and he soon had publishers queuing round the block.

The resultant tome, The Impending Gleam, sold 12,000 copies in two weeks. In 1980, in the art book world, this represented stratospheric success. It ushered in decades of steady work, publication in august titles like the New Yorker and gave rise to legions of cultish Baxter devotees – the core of who he claims are librarians.

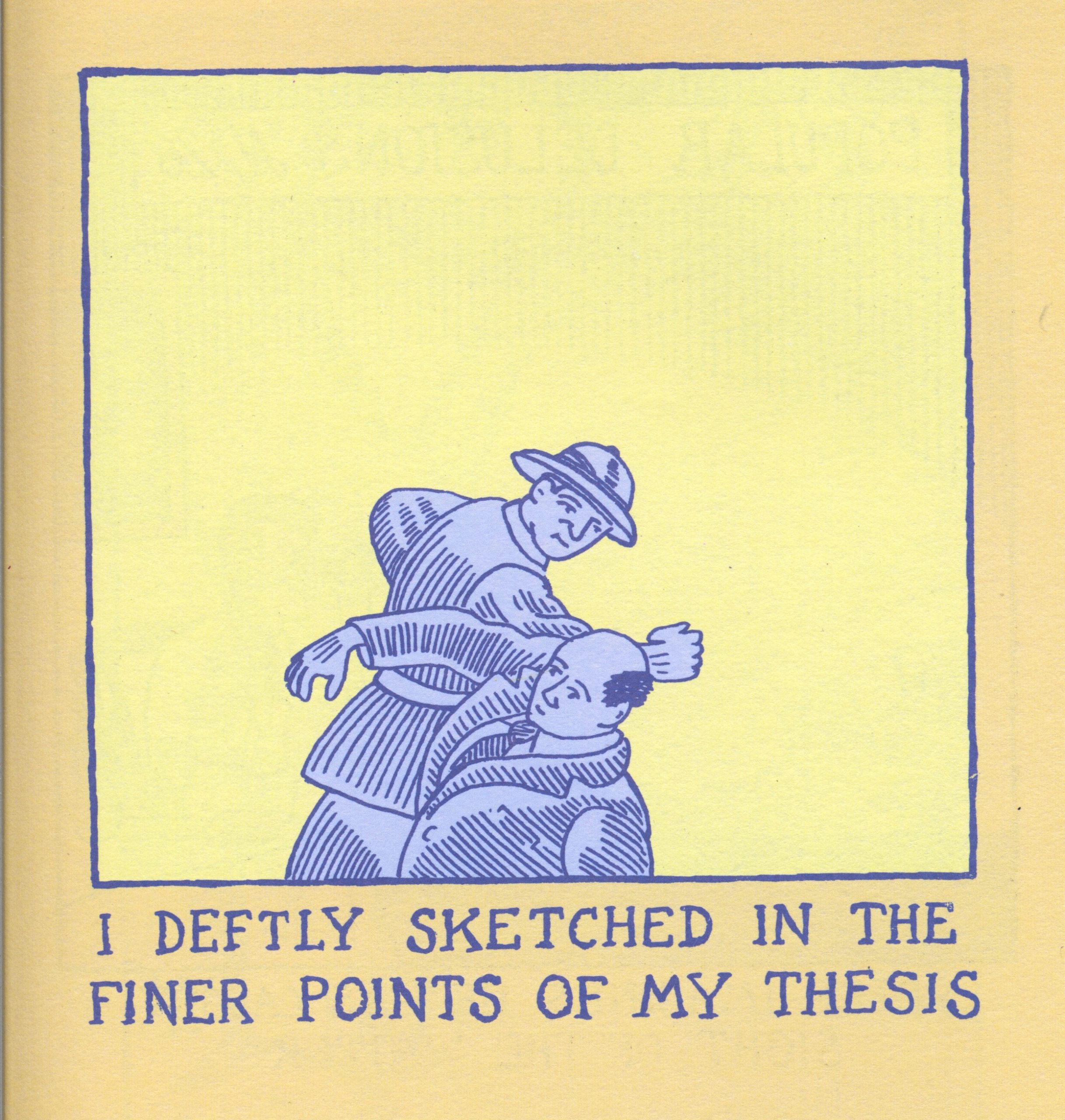

My favourite Baxter shows a tweedy monochrome man throwing a punch at another with the caption, ‘I deftly sketched in the finer points of my thesis.’ “I just wanted to use the word ‘deftly’ in a sentence,” he tells me, “it’s a forgotten word.” This says a lot about the time in which we’re living.

After draining his large Vinho Verde, Baxter rises and gestures towards the door. Outside he mounts a gel-seated mountain bike, bids a warm farewell and rides off into the south London night. Some say he lives in a small Martello tower, others a house. Much of what I knew of him before our meeting came from the convergence of rumour and fantasy—which is how it should be, with a surrealist.

–

You can see Glen Baxter’s work at Flowers Gallery until 1st Feb.

Click here for more information.

Flowers Gallery – 21 Cork Street, London W1S 3LZ.