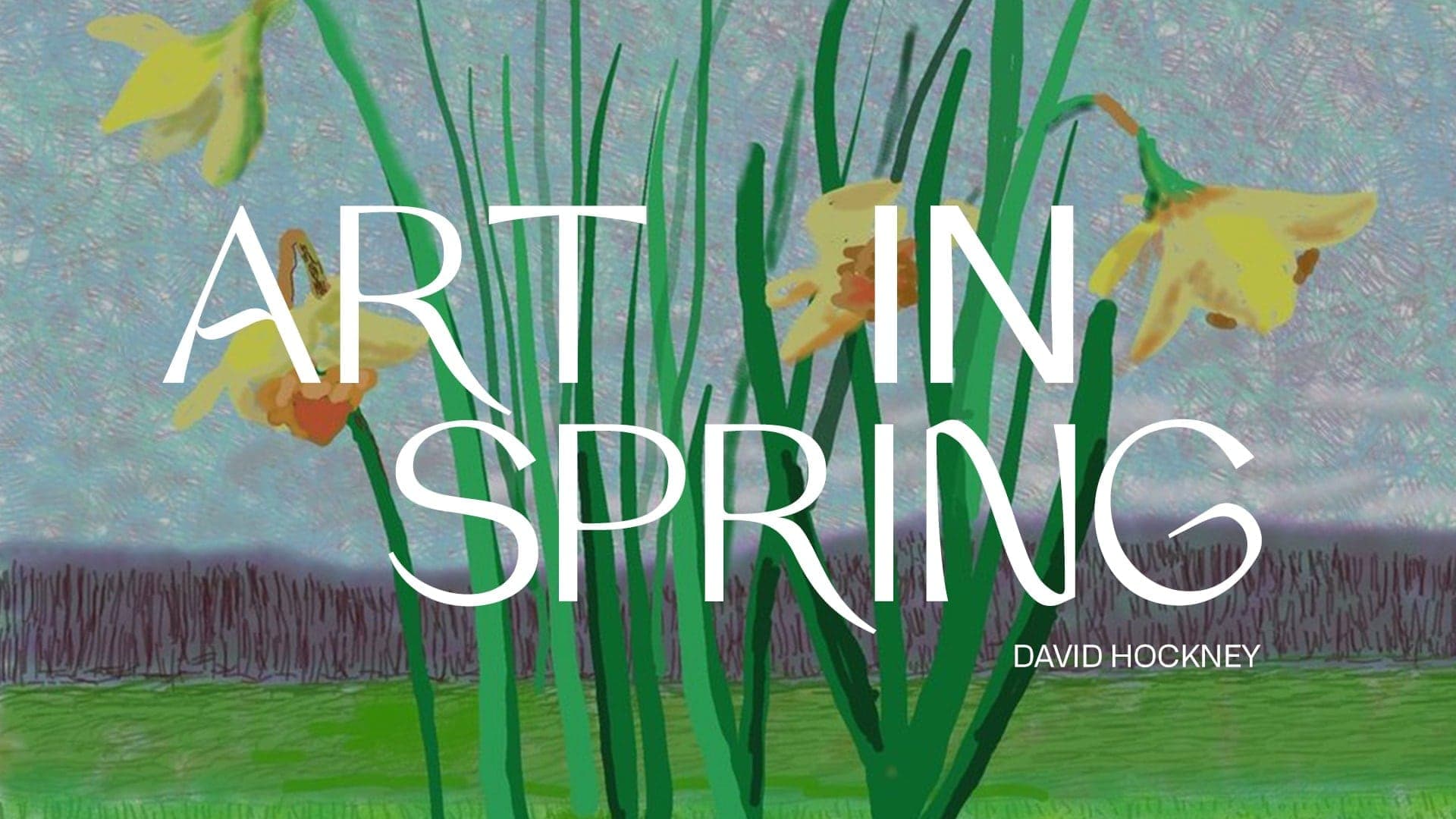

On the 18th March, David Hockney unveiled his latest painting titled ‘Do remember they can’t cancel spring’, and its message is clear. An image of hope. Daffodils with graceful, bowed heads shoot up from a vivid green meadow. In the background, a grey mass — perhaps a bristly crop — serves to enhance rather than dilute Hockney’s public service announcement: to not acknowledge the gloom and uncertainty at the back of all our minds during this time of crisis could seem saccharine, annoyingly optimistic.

An image of hope. Daffodils with graceful, bowed heads shoot up from a vivid green meadow.

Instead, moderated positivity: the hazy grey crop, the hyperactivity of the light turquoise and lilac cross-hatched sky, and the way the daffodil heads could be said to be hanging (as if stoically or in response to misfortune) balances the happy, Pop blaze of colour. These elements anticipate the viewer’s protestation — ‘Not everyone’s glass can be half-full all the time!’ — and generously and gently bring it into the work. This is optimism which seems entirely reasonable.

Daffodils are, of course, much returned to symbols of rebirth and new beginnings, synonymous with spring. Sometimes referred to as the Lent Lily, they can often be found on altar pieces depicting the Crucifixion and the Resurrection. In the East, daffodils are thought to bring wealth and good luck. John William Waterhouse painted the reliable spring-flowering bulbs to illustrate the myth of Narcissus (narcissi is the name of the genus) and made of them symbols for the wrong kind of loving. Throughout art history, artists have used the flowers for more than mere ornamentation.

Daffodils are, of course, much returned to symbols of rebirth and new beginnings, synonymous with spring. Sometimes referred to as the Lent Lily, they can often be found on altar pieces depicting the Crucifixion and the Resurrection.

For a strange, wayward, and pessimistic repurposing of daffodils — in stark contrast with Hockney’s — we might look to Vincent Van Gogh’s ‘Undergrowth with Two Figures’ (1890). It shows a couple wading through a restless profusion of daffodils. They seem hemmed in by trees of preternatural pink and blue bark. One tree in particular seems to block their path; indeed, it seems to obstruct the viewer, too, plonked in the centre of the composition. Out of so much brightness underfoot, Van Gogh conjures so much despair. Looking from Van Gogh’s painting to Hockney’s is to feel a soothing breeze on one’s cheeks.

ArrayUncomplicated, refreshing, Hockney’s daffodils take off from William Wordsworth’s. Hockney is often considered a ‘Pop artist’, and here he’s playing on our popular understanding of daffodils: Wordsworth’s experience of them — or something close to it — has had such a lasting impression on the cultural imagination. Wordsworth, of course, ‘wandered lonely as a cloud’, until he chanced upon some daffodils. By personifying them ‘Tossing their heads in sprightly dance’, Wordsworth evokes a sense of unity between man and nature. By the end of the poem, the speaker is ruminating:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

David Hockney is currently in complete lockdown in Normandy, Northern France, a situation that might easily put someone in a ‘vacant’ or ‘pensive’ mood. But by letting his paintbrush dance — in busy, scratchy lines — he has captured the excitement we all experience year after year of glimpsing that first, blooming ’flash’ of yellow after a long winter.

I’ll admit that, sometimes, I fall into the trap of cynicism. It’s a habit. It’s somehow ‘cooler’, so much easier as a posture than optimism. The optimist risks sounding cheesy or trite; possibly offending others who have had negative experiences; or coming across like a fantasist. The optimist can at times sound so sure — indeed, positive — about a future which is objectively uncertain.

I confess it took me a minute to consider Hockney’s new painting a little more deeply, to look beyond its postcard surface — I’m far more comfortable trapped in Van Gogh’s undergrowth. The overgrown and restless forest floor is somehow sturdier ground. There’s typically far more satisfaction to be found, it seems, in relishing its existential angst, rather than envisioning the couple’s possible path through the cagey trees and the bright waves of blooming grass.

I confess it took me a minute to consider Hockney’s new painting a little more deeply, to look beyond its postcard surface…

But then there’s another way to view optimism: the certainty that our human progress to date has been the result of our collective ability to understand things and craft solutions. All that dismissing optimism does is ensure more rapid failure. We have practical duties at the present time faced with the difficulties of the Covid-19 pandemic — social distancing, washing our hands, not travelling unless absolutely necessary, etc. — but we also have a responsibility to approach the situation with a helpful mindset. The right kind of optimism: tempered, reasonable, robust. Fortunately, there are artists willing us on.

That ‘flash’ — of colour, of sudden remembrance, of hopefulness, of clarity — is worth remembering. Hockney is right, it can’t be cancelled.