Sweep over pale, stratified volcanic rock and zoom in on the cradle of mankind: Ethiopia, 2010. Throngs of miners are rallying around an injured man, his leg stripped of flesh, down to the bone. Uncut Gems announces its high stakes: life and death.

The confusion affords the chance for two labourers to slip off unseen and strike lucky in a tunnel. One of them now holds a huge black opal. The camera moves closer and closer, slips seamlessly inside the precious stone and veers into a sweeping, cosmic play of colour: fiery oranges, nebulous blues, becoming flesh tones, indeed flesh — the sphincter muscles as viewed in a colonoscopy. In less than five minutes, we have journeyed through the universe and emerged through Adam Sandler’s arsehole.

ArrayMetaphors, sure. The desire for this black opal is buried deep within diamond dealer and gambling addict, Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler). Howard fails to concentrate on the colonoscopy, just as he fails to look inside himself and examine his contemptible, compulsive behaviour. Howard’s gambling has landed him $100,000 in debt to a loan shark, who happens to be his brother-in-law – he’s in Deep Shit.

But the gesture. Galaxy to colon. Here is a film unafraid to hurtle from the sacred to the profane, from profound vastness to our most excremental baseness. In this, auteurs Josh and Benny Safdie wed aesthetics with character, revelling in glorious ugliness: from the film’s props — see the gaudy, bejewelled Furby necklaces Howard proudly shows off in his shop — to its jokes.

Here is a film unafraid to hurtle from the sacred to the profane, from profound vastness to our most excremental baseness

When the black opal is smuggled into Howard’s office inside a container of frozen fish, he removes the gem from a stomach cavity, groans, and delivers a line that would be instantly iconic were it not so NSFW: ‘Holy shit, I’m gonna come!’ Bad taste begets uncertainty. Should I laugh or be disgusted? He almost seems serious. Later, when a sports bet pays off, Howard squirms with delight in the back of a cab. It’s clear his gambling problem really does have an erotic component.

In one of the first texts ever written about the addiction, ‘Dostoevsky and Parricide’, Sigmund Freud speculates that compulsive gamblers (like the Russian author himself) have an unconscious desire to lose. Gambling is a method of self-punishment, to relieve guilt. ‘The [gambler’s] passion for play,’ Freud says, ‘is an equivalent of the old compulsion to masturbate; “playing” is the actual word used in the nursery to describe the action of the hands upon the genitals.’

The science has moved on, of course, but Freud laid its groundwork. In the DSM-5, you will find that the gambler still needs to ‘achieve the desired excitement’. Recent brain-scan studies show that dopamine is released even when a gambler loses, which might explain loss-seeking behaviour. Similar levels of dopamine are also released at the moment of placing the bet — the excitement of risk and uncertainty in themselves, it seems, reward enough.

Like gambling, narrative rewards uncertainty. Will Howard be able to pay off his debts? What will he do with the gem? We viewers take just as much pleasure in the frustrated suspension of the answers to these questions as Howard does. Winning and losing are beside the point; what matters is pure drive.

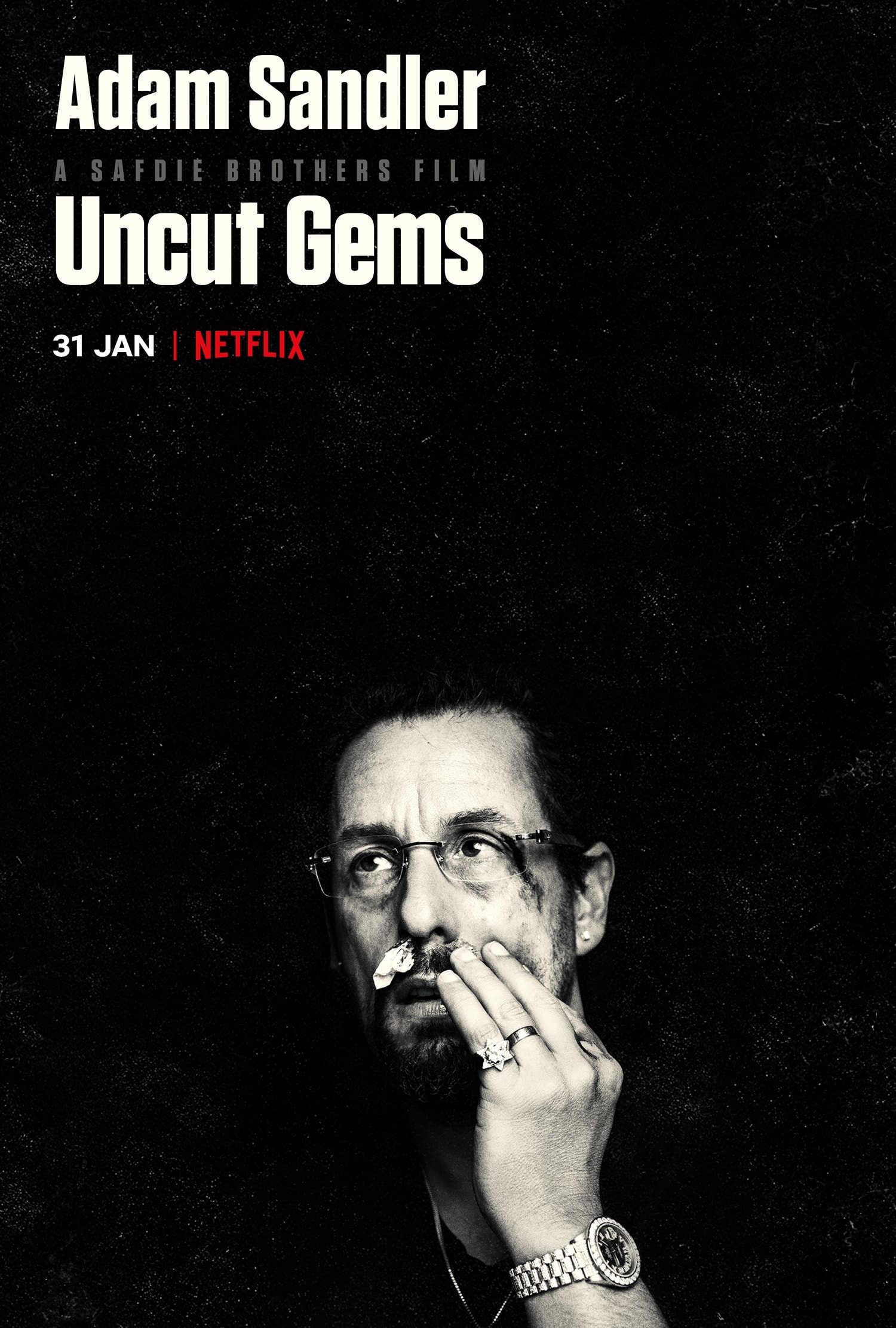

ArrayWhile this is true of any story, Uncut Gems plays with uncertainty and frustration in almost every aspect of its creation, from the Safdie brothers’ methods of filming (often working on location without permits) right down to casting. We are accustomed to Adam Sandler’s ability, both to annoy us and to act annoyed, being contained within the formulaic trappings of family-friendly comedies.

Casting Sandler out of type feels like a gamble. As does asking musician The Weeknd and basketball player Kevin Garnett to play themselves. There’s the sense that at any moment they might all realise they’ve been cast in a scuzzy crime thriller, which keeps heightening the spell of their performances when it refuses to break.

Casting Sandler out of type feels like a gamble. As does asking musician The Weeknd and basketball player Kevin Garnett to play themselves.

Then there’s Daniel Lopatin’s a.k.a. Oneohtrix Point Never’s score. Rather than working to simply heighten the emotional impact of a scene, Lopatin’s soundscape often runs in counterpoint, surprisingly gentle in moments of chaos, with Vangelis-like synth arpeggios that seem to unfurl in a narrative sequence all their own.

His music is present, characterful, in a way you might expect it not to be, and this only adds to the film’s sense of busyness, overload — as do the constant sounds of car doors slamming, electric buzzers blaring, multiple incoming phone calls, and different conversations happening at once.

ArrayWithin minutes of meeting Howard and seeing his pattern of self-destruction — the rickety scaffold of temptation, ad-lib and rage that shore up its repetition and escalation — your nerve-endings will have decided: I could never live like that. Uncut Gems gives us a cautionary tale; in the right doses, feelings of guilt and shame are crucial for an empathetic and just society, rather than one running on the fumes of our desperate self-interest.

Deep down, just like the Freudian-Dostoevskian gambler, Howard is so consumed by shame he wants to punish himself, to bring himself so low that the universe might see him for the wretch that he is. Caught between an ineffable vastness and utter debasement, the opal lives inside him. You can’t outrun fate, but Howard might wish he’d heeded that other maxim: quit while you’re ahead.