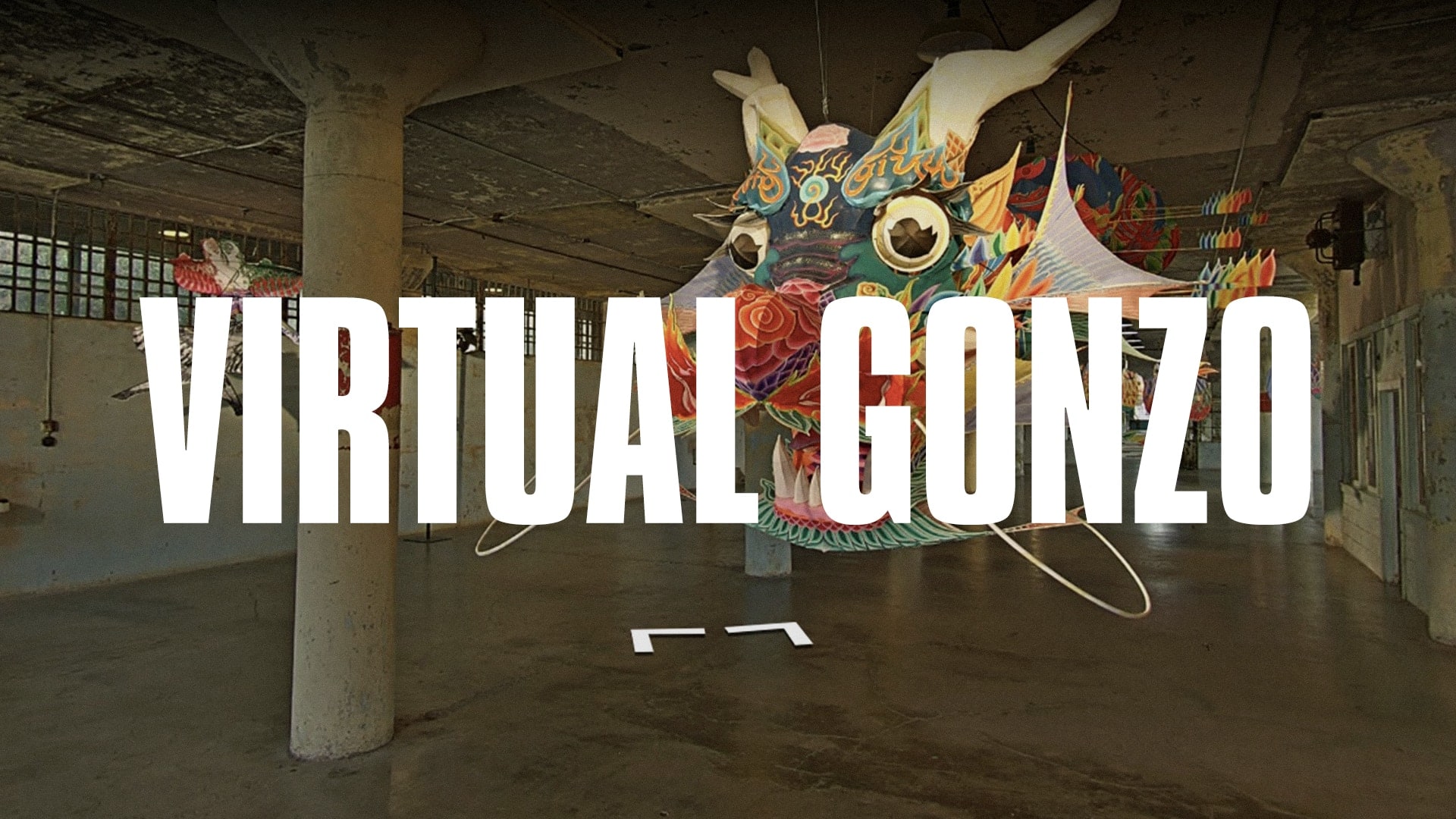

There’s a dragon kite suspended in Alcatraz. I’m on Street View, navigating to its head. Teeth bared. Eyes shaped like Twitter logos. This is Ai Weiwei’s ‘With Wind’ (2014): drifting in from a different century, the dragon slaloms between the flaked paint of pillars, rainbow-coloured against the cold, institutional light.

As I click forward, making my way under its body, I discover a quotation printed on one of the kites: ‘privacy is a function of liberty’ — Edward Snowden. It’s these details — quotes, the Twitter logo — that I find too on-the-nose in Ai’s work. As it tries to hold my hand, my childlike reaction is to slip away. Why not leave me alone with the dragon and let me discover my own freedoms and repressions alongside it?

See Nelson Mandela and Edward Snowden staring up at you, among more than 175 prisoners of conscience, past and present

Having said that, there’s no denying the work has a pull. Confined to a warehouse-like hall in a dilapidated prison, rather than soaring in the sky, our paper dragon says more about the human spirit and our attempts to restrain it than any of its quotations could.

Click my way to its tail, and encounter smashed glass stained by rusting wire mesh. Proceed through the door into an identical hall. This time colour is splashed across the floor, rather than near the ceiling. Carpets made of Lego. See Nelson Mandela and Edward Snowden staring up at you, among more than 175 prisoners of conscience, past and present. We’ve moved from metaphor to something like propaganda.

ArrayI google one of the names on the floor: Metinpour. After advocating for linguistic and cultural rights for Iranians of Azerbaijani ethnicity, Sa’id Metinpour was detained for the peaceful expression of his beliefs. Another Lego tile, and another quick search, reveals Shaker Aamer to be a British man who spent 5,008 days in Guantánamo Bay, convicted on circumstantial evidence during the paranoid period post-9/11.

But what am I meant to do with the prisoner portrait field depicted in ‘Trace’ (2014), besides remember them? Is that enough? It’s one thing to try and imagine myself into an exhibition in Alcatraz in 2014, another to imagine myself into Aamer’s cell, where he would befriend insects and name them in an attempt to keep himself sane.

You could hardly call it subtle. But then nor should it be, if its goal is to draw forgotten figures of dissent into the light of day

What to do when the inescapable pleasures of Pop — more than a million of those tiny Lego bricks I liked so much as a child laid out in Warhol-like arrangements — are clashed together with the Conceptual, which here reads like straight political appeal?

You could hardly call it subtle. But then nor should it be, if its goal is to draw forgotten figures of dissent into the light of day — or, ironically, into the grungy gloom of rocky Alcatraz.

Maybe what I’m resisting, when it comes to Ai Weiwei’s work, is the idea that any art can affect political change. But then, might I be able to start with small concessions? Navigate through the old dining hall and you come to ‘Yours Truly’ (2014): two teak racks housing postcards pre-addressed to some of the prisoners in ‘Trace’; visitors were invited to write to them.

Am I so cynical as to think the incarcerated people reading these messages would not have experienced an interruption, however brief, of their profound isolation; that they would not have felt remembered, even if momentarily? No, I’m not. So why can’t I imagine our paper dragon riding out on the winds of change?

As Ai puts it, ‘When you constrain freedom, freedom will take flight and land on a windowsill.’ It seems fitting to visit Ai Weiwei’s @ Large on Street View, because the artist has never set foot in the notorious prison, either — his passport was in possession of Chinese authorities at the time of its installation. Instead, the exhibition was executed with detailed maps, plans, Skype, videos and a score of assistants.

Creating site-specific art for a place he couldn’t see was a challenge Ai embraced: free expression, under severe constraints. To a lesser degree, that’s the aim of this series: to be on the wing, visiting places, even when stuck inside. And that’s not something I’m struggling to grasp, not one bit.