First, we drifted on Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s ‘Floating Piers’ in Italy. Next, we traded lockdown for lock up, with Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz. We walked The Line, in East London. We found Kara Walker’s sphinx guarding the abandoned Domino Sugar Refinery in Williamsburg. Then, we met the dolls who have overtaken the human population of the sleepy village of Nagoro, Japan.

Last time, we dug deep into the icy isolation of Scott’s Hut, which sits on the tip of Ross Island, Antarctica. And now, we visit a troubled neighbourhood in the hills of Pachucha, Mexico, and the street art campaign giving it a new lease of life.

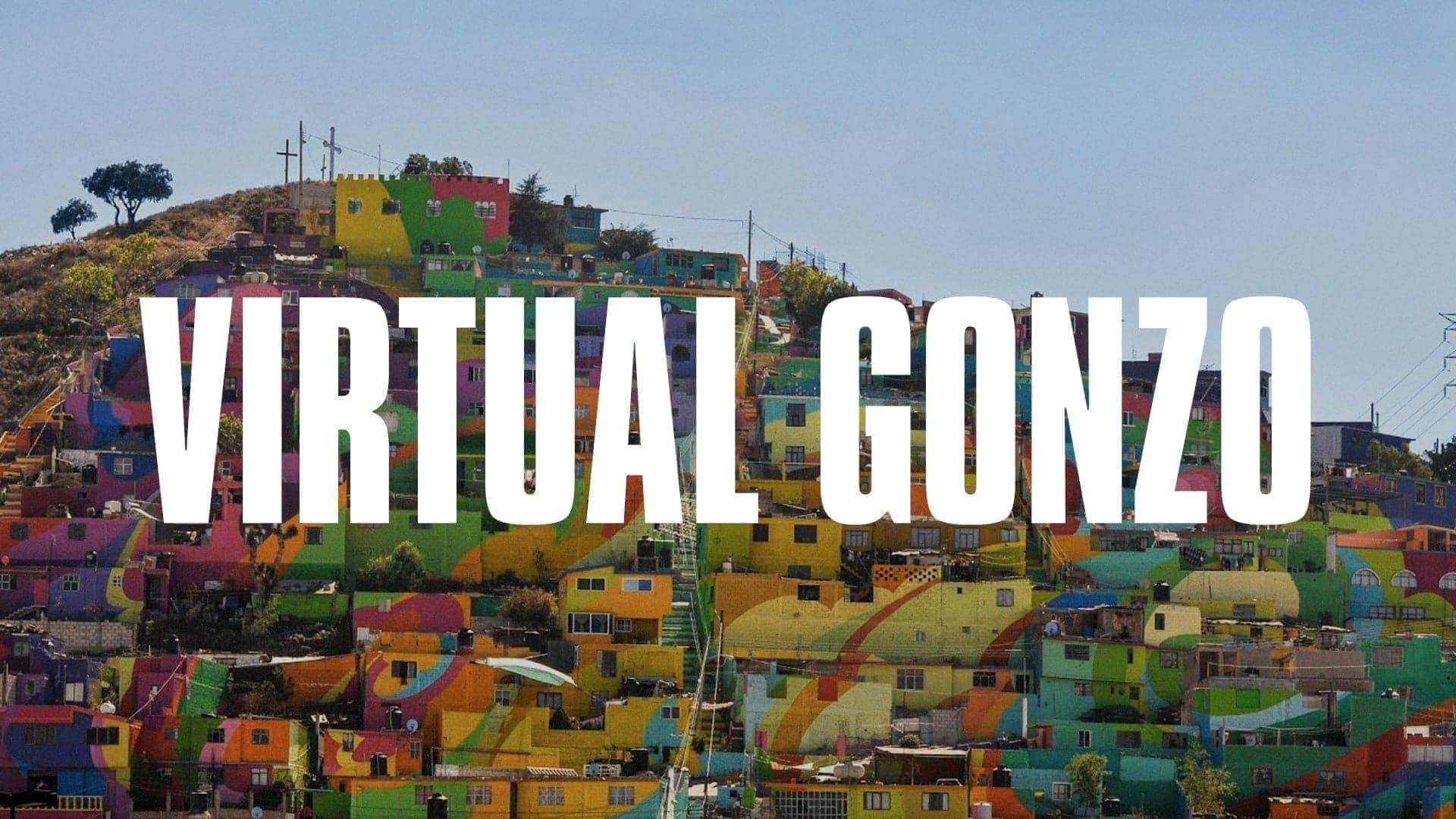

Dark clouds are rolling in. But this neighbourhood’s already been rained on – with 20,000 litres of paint

Governments typically devote resources to removing street art. Then, occasionally, they sponsor its making. I’ve decided to get a Street View of Mexico’s largest mural, which was commissioned as an attempt to reduce crime and unite the Palmitas neighbourhood.

Dark clouds are rolling in. But this neighbourhood’s already been rained on – with 20,000 litres of paint: lime green, teal, bright blue, day-glo rose, lavender. Vibrant colours spread wall to wall. Washing is hanging out to dry. Huge cacti grows by the roadside. Stray dogs totter along the pavement.

As inspiring as it can be in action, ‘urban renewal’ is a flat and bureacratic phrase. It strikes me as a handy euphemism to brush over all the reasons a place got so blighted in the first place. I’m resistant to the idea a town can be painted happy.

However, navigating the barrio in Street View is revealing. Some of the streets don’t have a post-2015 capture, and to be returned suddenly to drab cement-and-cinder block pre-paint is jarring; you’re keen to click your way back to life in hyper-colour.

All this colour sweeping from home to home enacts the communal intergration it aspires to; every household is quite literally part of a Bigger Picture

As satisfying as it is to see the bright, geometric paintwork up close, you also find yourself wanting an overview. Seen from afar, these abstract patterns combine for a swirling rainbow design, an homage to the wind, since Pachucha is nicknamed la bella airosa, the beautiful breezy city. All this colour sweeping from home to home enacts the communal intergration it aspires to; every household is quite literally part of a Bigger Picture.

The artists’ collective known as the German Crew spent 14 months making it all happen. Rusted-out, junked cars were removed, street lights installed, along with CCTV cameras. First the houses were painted white, the colour of peace, as if to say: we’re starting from scratch.

ArrayThe collective worked hand-in-hand with residents, some of whom were in rival gangs, to persuade them to let them paint their houses. This was a hillside slum where gangs regularly fought turf wars. They probably still do, but officials claimed in 2015 crime rates were down 79% as compared with 2012.

The question remains, however, is this merely painting over poverty, or a valid way to intervene in a downtrodden neighbourhood? I don’t know. Googling for answers, residents seem happy, crime seems to be down, but are those trusted metrics for quality of life?

The question remains, however, is this merely painting over poverty, or a valid way to intervene in a downtrodden neighbourhood?

Still, would you rather live in a slum riddled with cartel-related violence or in one of the world’s largest murals, which sees pop stars (Sigala and Ella Eyre shot the video for ‘Came Here for Love’ in Las Palmitas) outside your door? Even if both are true, one instills more pride and hope than the other.

German Crew’s intervention in Las Palmitas was such a success that the project expanded to the adjacent Cubitos neighbourhood. Eunice Rendón, who is in charge of the nationwide programme to rehabilitate neglected barrios, says he has a queue of demands from other cities to get the same treatment.

Mexico has a rich history of muralism, which has always intricately woven in social and political messages. Take ‘Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park’ (1946-7) by Diego Rivera, which depicts famous events in Mexican history and hundreds of people jostling for space. For all its lightness – a bunch of bright balloons, impeccably dressed visitors, vendors selling their wares – it simultaneously erupts with violence: a policeman confronts an indigenous family in one passage, while elsewhere someone is trampled by a horse.

For all its lightness, it simultaneously erupts with violence

Rivera’s work is vast by usual standards, but a drop in the ocean compared to German Crew’s sprawling tableau. Breathing vitality into long-passed-over hillside slums, they also reinvigorate the mural tradition. If Rivera painted Mexicans from all strata of society united in one bustling panorama, German Crew inverted it. Brought the paint to the people.