165 years after the birth of America’s most iconic writer, Harvey Solomon-Brady remembers Mark Twain’s affection for the city that celebrated and consoled him.

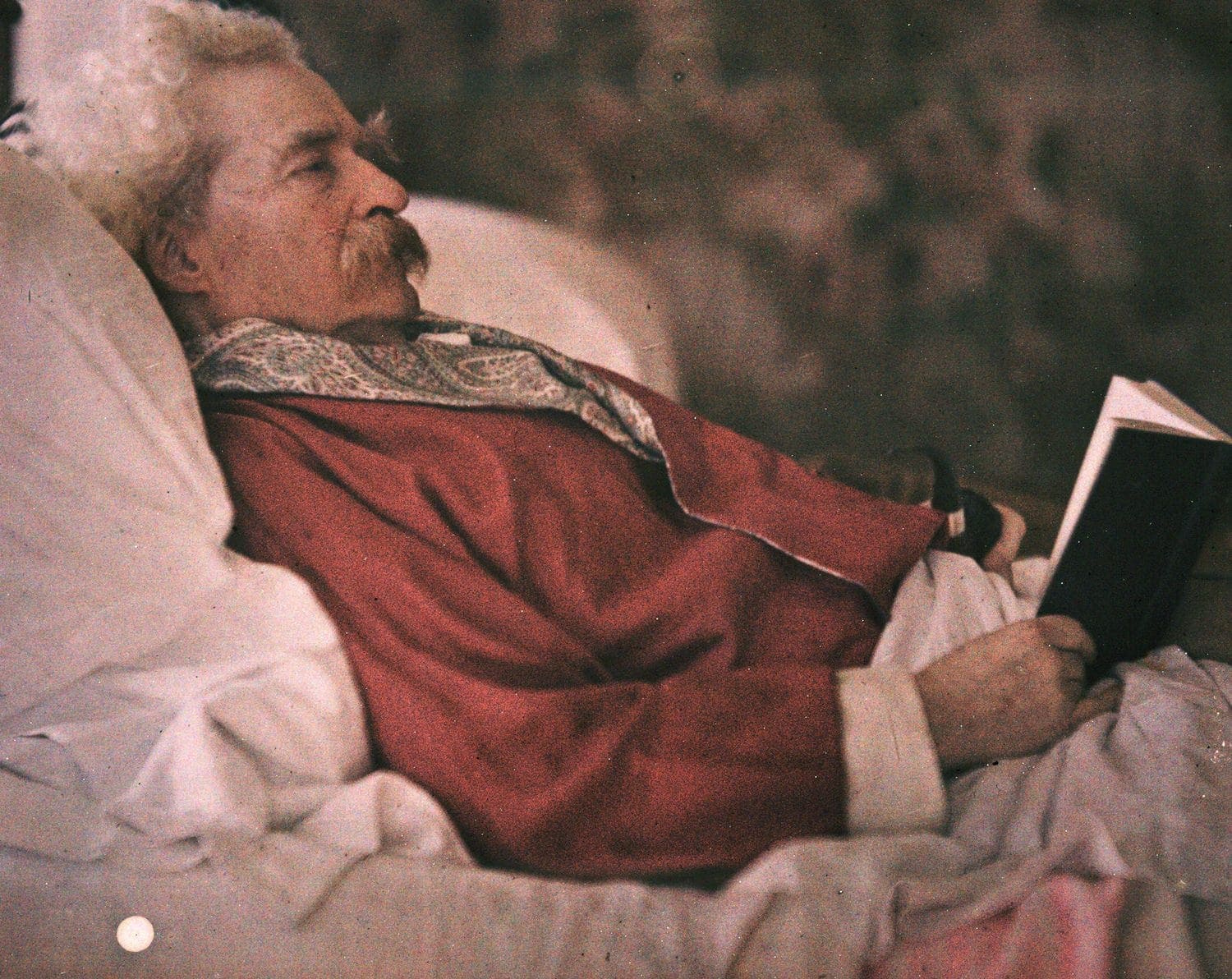

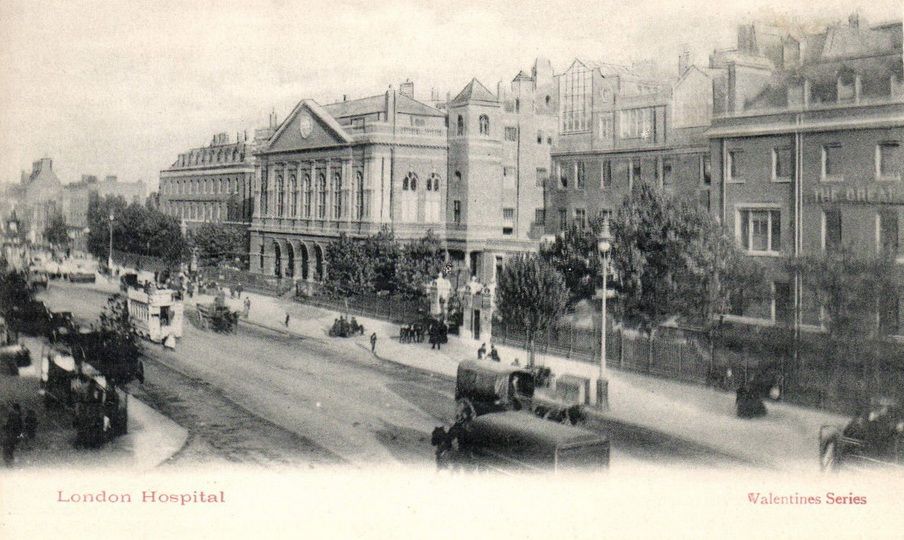

Twain reading in bed, 1908 Autolumiere photo

“When I stand under the English flag, I am not a stranger.”

And so Mark Twain first observed on his maiden trip to London that he was no alien in our land. Samuel Langhorne Clemens – he adopted the moniker Mark Twain after a boatman term heard often in his native Mississippi – visited the city as often as long haul travel and his own popularity permitted, first in 1872 and lastly in 1907 on a journey to collect an honorary doctorate at Oxford University. The father of American literature enjoyed all the delights the capital has to offer, but most impressively experienced its ability to help cure his grief after the death of his daughter.

Ever the humourist, Twain liberally remarked on the peculiarities of British life, writing at length to his wife Olivia about his grand receptions whenever his name was read out on guest list dinners, of which there were many. Twain’s misgivings about London’s high society was there was “too much dining, too much sociability”, but the criticism of attending salons ended there, with the author enthusiastically accepting honorary membership of the Savage Club in the 1890s. When told that he was just one of three to have been bestowed such a privilege, including the Prince of Wales, Twain quipped: “Well, it must make the prince feel mighty fine.”

Twain enjoys a cigar with Lord Balfour (left) and Komura Jutaro (right) on the terrace of the Houses of Parliament

Twain wearing his Oxford robe upon becoming an honorary Doctor of Letters in 1907 (he proudly donned the piece at parties for years after)

But the Huckleberry Finn author most evidently left his mark on a normally dark enclave of London, far away from the candelabra laughs of his thousand-dollar-a-night dinner speeches. It was 1897 and Twain had been in the city for a European book tour. Plans to return to his old haunts – St. Paul’s Cathedral and the British Museum reading room in particular – were dealt a blow as the excursion was clouded with the news from America that his favourite daughter Susy Clemens, 24, had been taken ill. After a few tense days Twain, accompanied by his wife Olivia and his eldest daughter Clara, received the news that Susy had died. Unable to book passage for all three back to the States, Twain stayed alone in London, spending many languid days inside his Chelsea apartment but nevertheless honouring his speaking engagements.

One of only a few friends this side of the pond was a Ms Adele Chapin, a wealthy American who recounted in her memoir Their Trackless Way how unhappy and restless Twain was at the time. He’d pace up and down her living room and say: “If I was a god, I would be ashamed to treat my children so. Don’t talk to me about a Heavenly Father, no human father would behave how God does.”

Mark Twain with family seated outside, circa 1865. (Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images)

London home of Mark Twain and family, 23 Tedworth Square, Chelsea

Chapin’s quiet resolve and accommodation of the grieving Twain did not go unnoticed by the distraught father. After he collected himself a few days into this dark chapter, Chapin recalled how Twain said: ‘Do you know, I believe I would do almost anything you wanted me to do.’ He wasn’t expecting her request. Adele Chapin worked as a volunteer at the London Hospital and asked if he’d come and regale the patients there with some of his stories.

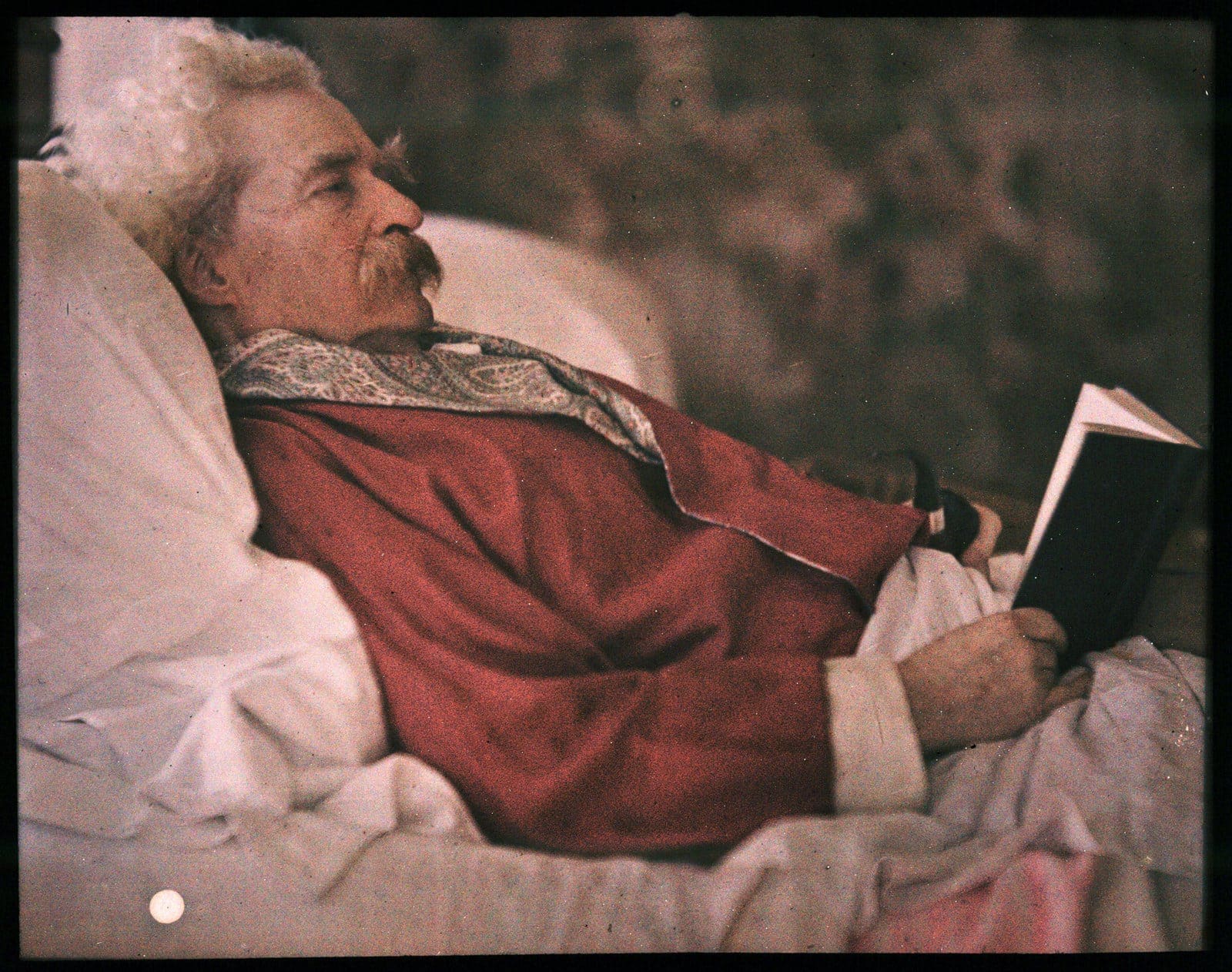

And so it was with Herculean effort from Twain that he agreed to address the infirm and dying just as he was grappling with his own grief. The old Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel was the biggest infirmary in the city in 1897, and at the time Mark Twain was already among the most famous men on the planet. Indeed, mere seconds after walking through its doors, word had spread far and wide through the polished corridors that the author was in their midst.

A 19th century postcard depicting the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel

Medical staff and patients crowded into the cramped ward Twain was visiting. “It was an audience of sick and dying men,” remembered Chapin, “some of whom had begged to stay, and turned their faces from the wall to laugh again. Mirth struggling through pain on their faces was wonderful to see, and their eager listening not to lose a word.”

Nervously, Twain concentrated on plying his trade by dazzling the sick with tall tales of his own childhood. His words were soundtracked by piano and violin, played by a pair of young ladies from the London Hospital Music Society. Twain selected some highlights from his almost infinite inventory of anecdotes. He began with a story of when he stole a watermelon but, on discovering it was unripe and bitter, returned it to the irate farmer and demanded a fresh one – and got it. He ended by performing a run-through of his calamitous first attempt at horseback riding, an initiation that resulted with the Mexican mule “shooting poor Mark high into the air, so that he lost all count of distance, and only knew that he passed birds along the way.”

The performance was greeted by a resounded round of applause, one patient declared: “It was a bit of orl right, I give yer my word.” Twain had too enjoyed the day, so much so that on the way home he confided to Ms Chapin, with tears in both of their eyes: “I have never had such an appreciative audience.”

It was in this natural disposition of the poor and sickly Londoners towards gratitude and appreciation that Samuel Langhorne Clemens identified. It is also why when we read his novels, set an ocean away and more than a century old, we smile at his tact for framing life. Indeed, he is not a stranger.