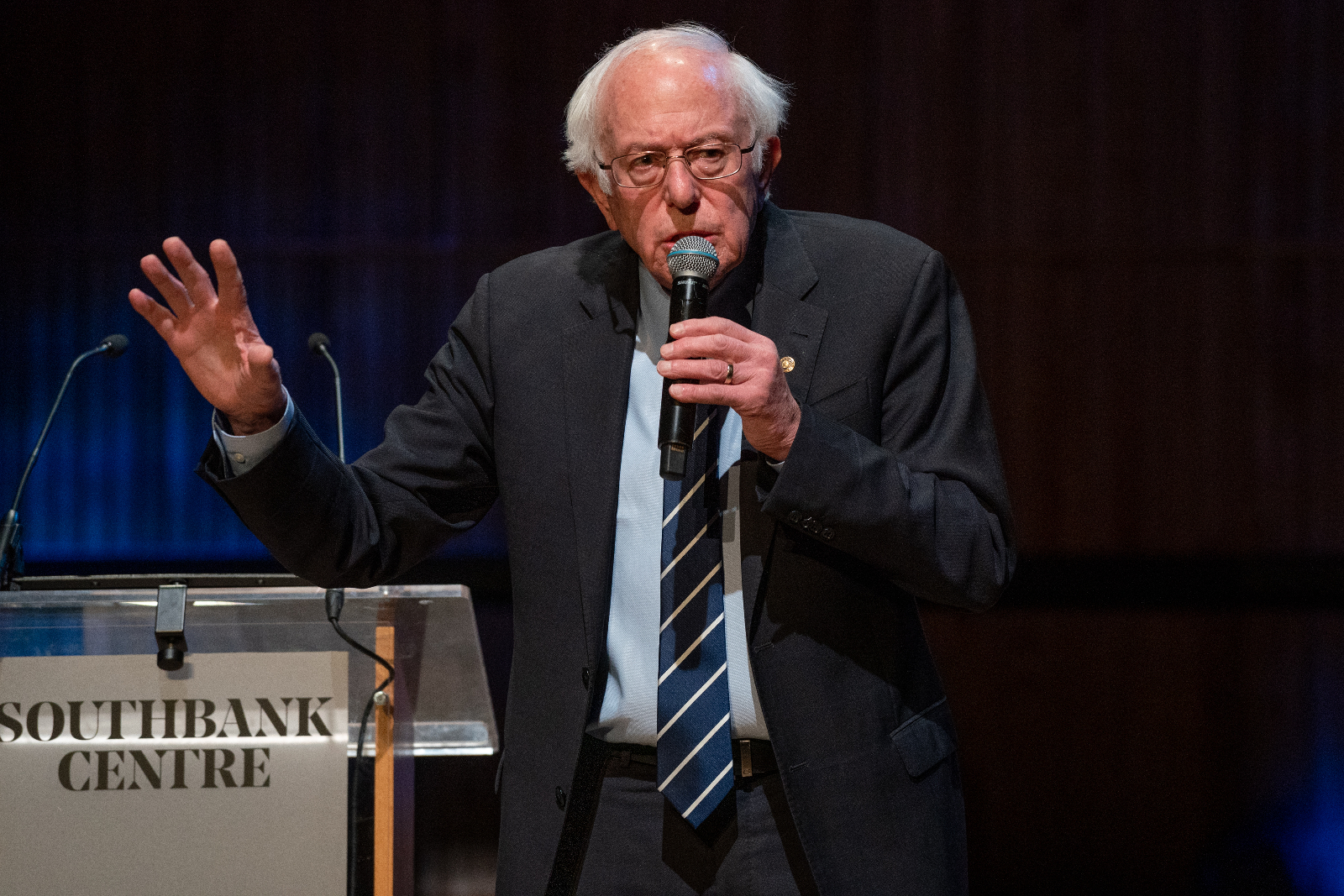

It turns out Bernie Sanders is a very funny man. Politics aside for a moment, his timing is impeccable, and his fondness for subtle, self-deprecating humour seems rather British. It makes you briefly wonder… What if he was?

He couldn’t be, of course. He simply couldn’t be. Even as one of the most vocal critics of America’s status quo, Sanders is a direct product of the United States, and to pretend an occasional tendency to take the piss out of himself (an exclusively British ability) equates to his unmistakable Americanisms, is silly. Bernie couldn’t be British.

Photo Credit: Pete Woodhead

Still, the evening made me consider the possibility – especially after Jeremy Corbyn and his wife became the final two guests to enter the Southbank Centre auditorium and take their seats a couple of rows in front of me. A murmur of surprise and expectation met their arrival.

There are obvious similarities between the pair, yet in recent years the facile, transatlantic comparisons have been dominated by a pair of populist blondes. What of the socialist silver foxes?

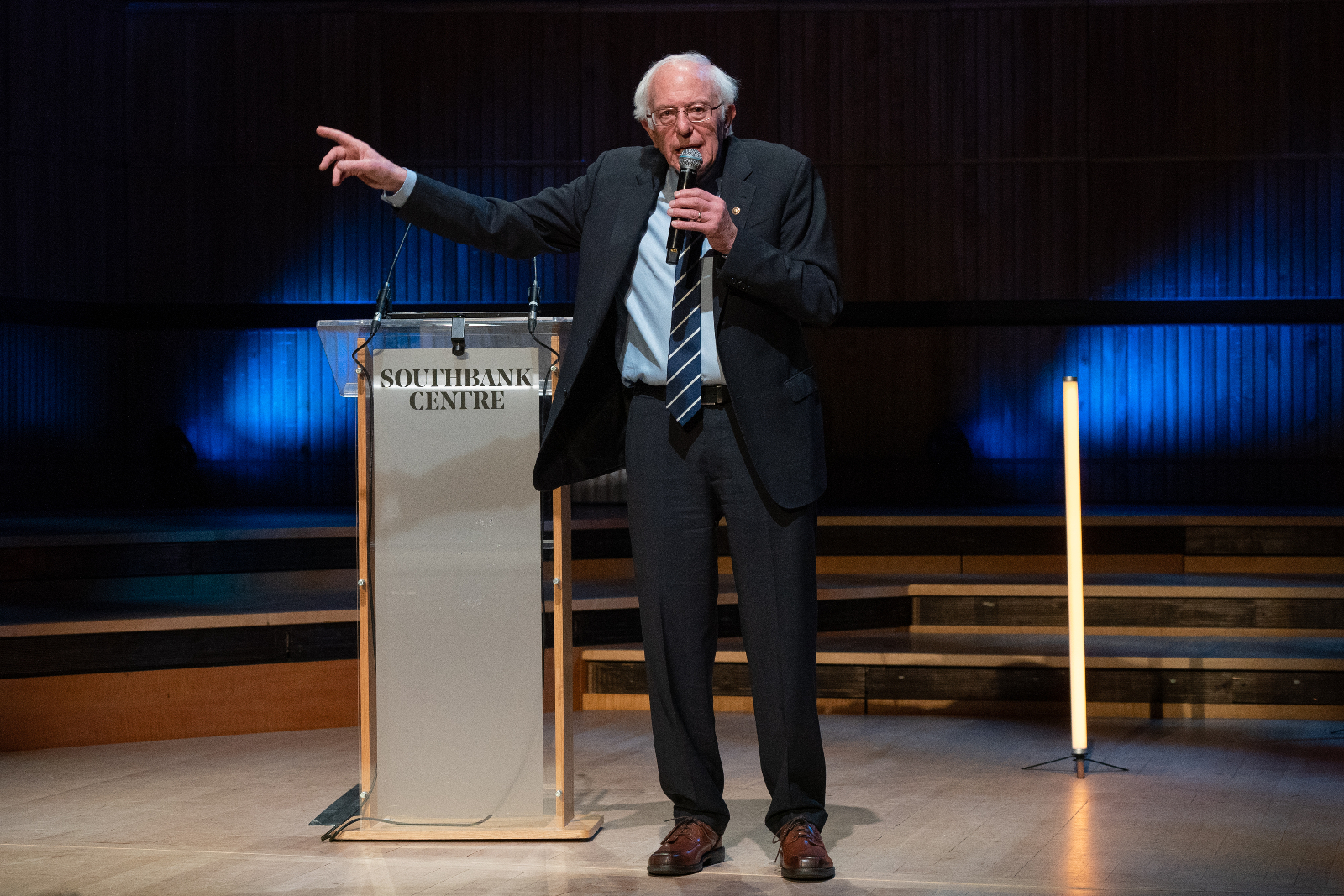

Over his 90 minutes on the Royal Festival Hall Stage (which is free to watch here until 2 March), at first by himself and then in conversation with the impressive Emma Dabiri, Sanders inadvertently ridiculed any equivalence between himself and Corbyn. He demonstrated ability, intelligence, nuance, charisma and clarity. Where the Boris and Trump resemblance was lazy and inaccurate, those still place Corbyn in the same breath as Sanders live in LaLa Land.

I’m not here to argue the efficacy of left-wing policy, nor to wade into the inescapable, toxic quagmire that became the Labour Party towards the end of Corbyn’s reign, but rather to fleetingly examine how Sanders seems to have better navigated the pitfalls that have consumed so much of progressive politics over the last decade.

Bernie Sanders and Emma Dabiri.

Photo Credit: Pete Woodhead

Most notable was the sheer coherence of Sanders. He may have been blessed with a wit and a grandpa-like, mitten-clad charm, but the knowledge of his own argument is faultless, and he does not dither. Crucially, for a politician, you know where he stands.

He can also combat criticism without the smug, spiteful, self-righteousness polluting large parts of America’s – and indeed Britain’s – left-wing conversation. Sanders is angry, but – other than mocking Bezos and Musk and their trivial, rather phallic obsession with who’s got the biggest rocket – he never turned an accusatory eye towards the tens of millions of ordinary Americans who consider him a radical extremist. These people are, in his view, victims of the same American class system that he rallies so tirelessly against. Disagreeing without insulting is a dying art.

Also interesting was his fixed focus on the economy. Since 1992 and the phrase “It’s the economy, stupid” used in Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign, the left has seemingly gravitated away from the small matter of money. For all the furore around the social context of both the Trump and Brexit votes, I would argue that, primarily, these were referendums won on economic autonomy.

Bernie Sanders and Emma Dabiri.

Photo Credit: Pete Woodhead

Sanders is adept at negotiating tricky topics. Following a good question from Dabiri, he did not explicitly attack identity politics or what would be classified as ‘wokeness’. Still, he warned of its dangers, cautioning how it can distract from a genuinely progressive policy that he believes would benefit all. He was never impolite or ‘politically incorrect’, but he certainly did not let semantics cloud his overarching message of common humanity, a widening chasm between classes and the need to reestablish the focus on these issues.

His ability to articulate a multi-faceted issue was also displayed regarding social media. In a complex debate with no clear resolution, Sanders could boil it down to the “fundamental challenge” of preserving the freedom to disagree without allowing the spread of hate or misinformation purporting to be fact.

It is refreshing to see somebody not claim to know the answer, having successfully identified the problem. That takes humility, arguably Sanders’ greatest strength of all.