‘See Naples and die’ as the old adage goes, and Leopardi did just that – but not before being seduced by the culinary excellence of Campania. Being a poet and philosopher in early 19th century Italy was hungry work indeed, and Leopardi’s gastric-obsession can be gleaned from a list of forty-nine of his favourite dishes which he inscribed onto ivory paper just before his death at a mere thirty-eight years of age.

A blazing meteor in the inky sky of Italian literature, it would seem odd to overlook his Canti in favour of something which effectively reads like the menu of a half-decent trattoria, but this document, though seemingly inconsequential, is a record of Italian cooking of the day, and of the culinary passions of this giant of European verse. The plethora of dishes range from the sublime (‘fried zucchini blossoms’) to the rather vague (‘pumpkin or salad with meat-filling’). From this delectable collection one of the humblest foodstuffs stands out – gnocchi, made from either semolina or polenta, appears as numbers thirteen and fourteen on the list.

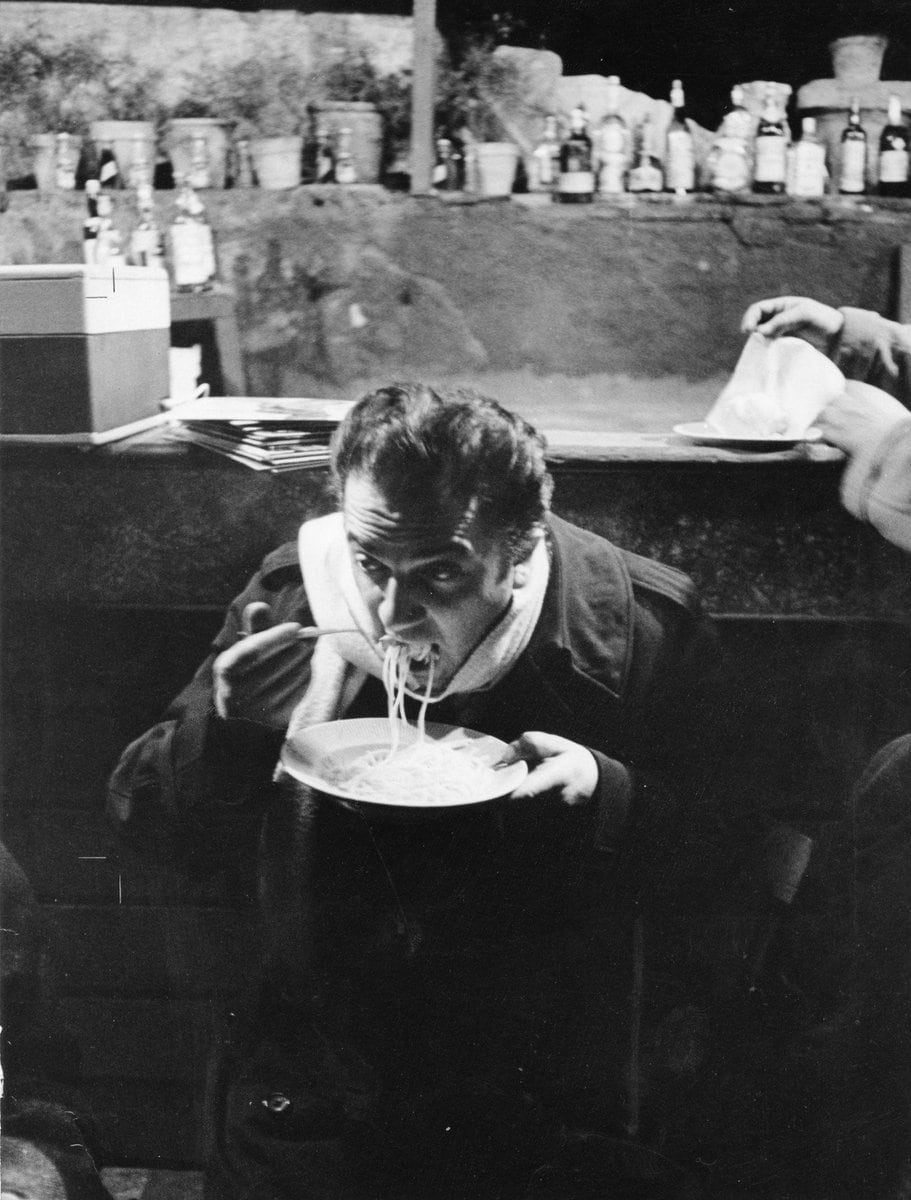

Left to right: Italian actors Mino Doro and Marcello Mastroianni (1924 – 1996) with director Federico Fellini (1920 – 1993) on the set of ‘8 1/2’, 1963. (Photo by Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

These stodgy little dumplings may seem of little significance, but another maestro, one whose final work was completed a century and a half after Leopardi’s, chose to incorporate them into his wonderful, if flawed, cinematic swan song.

Though a coincidence, it is still fitting, given the gourmand-status of both men. Federico Fellini’s 1990 La Voce Della Luna, an adaptation of Ermano Cavazzoni’s novel Il poema de lunatici, is certainly no masterpiece, and was not received as such – at times it feels bloated, dislocated, and a shadow of his earlier triumphs – a parody of Fellinian satire, but it still sparks with magic.

Roberto Benigni’s Ivo Salvini, under the influence of Leopardi’s writings (which mention the Moon over five hundred times) and the calls of the Moon herself, wanders a fantastical reimagining of the Po Valley, bewitched by an earthly beauty he believes to actually be celestial. Skirting the edges of sanity, we find a vacuous, media-obsessed society splaying the chasm between tradition and postmodernity.

ArrayIt is here where the gnocchi come in: one of the set pieces of the film is at La Gnoccata – a festival crossed with a beauty pageant celebrating this simplest of foodstuffs. Though the town around which the film centres is as much a figment of Fellini’s imagination as the landscape his protagonist nocturnally roams, the festival itself is real. The millers of the town of Guastalla began La Gnucàda (as it is known is the Emilia-Romagnan dialect) around the time of Leopardi, though there is no record that the poet, who gorged his way around the yet-to-be-unified Italy, saw it.

The modern festival is more like a renaissance fair than the flour-spattered debauchery of Fellini’s vision, though the crowns worn by the rather grotesque mascots dressed as huge dumplings and the demented jester are a nod to this tradition. The whole town turns out to stuff themselves. Ivo opts for his portion to be served as his grandmother used to do it – the potato dumplings, so delicate that they ‘melt in your mouth like zabaglione’, are drenched in sauce and dusted with cheese.

However, his love of this pasta dish is eclipsed by his blind fury, as when he sees the winner of ‘Miss Farina ‘89’, Aldina, the object of his desires, dancing with another man, he commits a crime of passion, slapping the steaming bowl of pasta onto the head of the elderly gentleman before fleeing the scene just as the fireworks begin. A comical demonstration that some things in life are more important than gnocchi.

A scene from ‘Amarcord’ in 1973 in Rome, Italy. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

The director’s tastes might be traced to his upbringing. Whilst it was Campania which inflamed Leopardi’s love of the gourmet, for Fellini, his native Emilia-Romagna, revered throughout Italy for its hearty cuisine, was where he received his gastronomic initiation. This part of northern Italy is the cradle of many of the icons of the world’s most beloved cuisine: Parmigiano Reggiano, balsamico, even the oft-bastardised Bolognese sauce has its origins (unsurprisingly, given the name) in the region. The fertile plains of the Po Valley have contributed to the abundance of incredible produce from here.

This is the countryside where the crops which sustain and plumpen the people of the region are grown, harvested under the apricot-tinted lunar glow of late Summer. So rich is the food of Emilia-Romagna that one nickname for the people of its capital, Bologna, is la grassa, ‘the fat’. John Berger ruminated upon the city’s comestible heritage in The Red Tenda of Bologna, these are the brushstrokes by which he paints this recollection of the mystery of the city, and his distant youth. ‘Oh, to be a cow in India, a cat in England, a child in Italy!’ is a saying which carries great significance – Italian children eat well, and the young Federico, growing up in Rimini, a small seaside town, was no exception.

The rustic fare consumed by the family in Amarcord (1973) mirrors the meals he ate growing up, though as comforting as the food appears, it cannot quell the tension between characters. Fellini claimed that ‘it is not memory that dominates my films’, but one can find glimmers of childhood nostalgia and adolescent angst in most of his works, from I Vitelloni (1953) to his final farewell.

ArrayHowever, to say that the inclusion of food in his films is autobiographical would be wrong; his works represent all lives, not just his. The groaning mounds of pasta consumed at the wedding feast in La Strada (1954) speak of abundance in the post-War period, whilst in the same film the death-defying feat of the ‘Fool’, who balances a dining table on a tightrope forty metres above a thronging crowd, whilst eating spaghetti, suggests the idea of dining as spectacle.

This idea that even the humblest of meals can be extraordinary is revisited during the festival scene of La Voce Della Luna. Furthermore, in 1984 he directed an advertisement for Barilla pasta, called Alta Societa, a strange, dreamlike restaurant sequence with Nino Rota’s hypnotic La Dolce Vita theme in the background. In the advert, having listened to the recitation of a menu of French haute cuisine, the woman ordering instead asks for nothing more than some rigatoni (Barilla, of course) – a refutation of Gallic pomposity in favour of earthy Italian cooking.

The director famously remarked that ‘life is a combination of magic and pasta’, the circus runs on blood, sweat and starch. In an ever-changing world, the pasta is a constant.

Fellini munching on some pasta

It’s to be expected that a baroque Master of Film would be prone to indulgences, and for Fellini it wasn’t just pasta which he had a seemingly insatiable appetite for. He once quipped that it is ‘easier to be faithful to restaurant than it is to a woman’, hardly a revelation given the proliferation of adulterous, semi-autobiographical characters in his filmography. The conflation of desires both carnal and culinary is nothing new. Leopardi used the image of romantic words from Elvira, a ‘divine beauty’, being the ‘food and sustenance’ for Consalvo, the ‘unhappy lover’ of his verse as he nears the end.

Fellini played with the idea, such as the Act he directed in Boccaccio ’70 (1962) where the prudish Dr. Mazzuolo is seduced by a giant billboard of a buxom Anita Ekberg advertising milk, tempting him into immorality, and, before long, insanity. By contrast the gnocchi scene from La Voce Della Luna seems incredibly tame, the beauty contest to be the next Miss Farina seems decidedly non-sleazy in its innocence. Ivo’s childish response to seeing his crush, the newly crowned beauty queen who has shown little but contempt for him, dancing with another man would not be as striking, nor as amusing, had he not sacrificed a delicious, sloppy bowl of gnocchi in order to humiliate this perceived love rival.

It’s certainly a comical scenario, but one demonstrative of Ivo’s passion: lust and gluttony, the driving forces of Fellini’s life. La bella figura, the art of making a good impression, is intricately connected to what you cook and what you consume – a reputation marches on its stomach, and a man’s prowess is tantamount to his hunger, Ivo, feeling himself cuckolded, has lost his.

Director Federico Fellini in a scene from the film ‘Fellini Satyricon’, 1969. (Photo by United Artists/Getty Images)

If cinema is the essence of life woven into poetry, then food provides the rhythm to that poetry: three meals a day, seven days a week, the rest is magic. The voices which stalk Ivo he believes come from the Moon, a Moon which brilliantly illuminates the fantastical Emilia-Romagnan countryside which Fellini has created, the whispering grasslands providing a serene escape from the dystopia he creates.

Ironically Ivo, recently released from a mental hospital, seems comparatively sane compared to those he encounters on his pilgrimage. Alone at the conclusion, and taunted by the Moon, bearing the face of the woman he obsesses over, he reflects that if there were more silence ‘maybe we could understand something’ before tearing his gaze from the sky and downwards into a well, an intriguing twist on the Chinese proverb of the frog who doesn’t see the full picture. Fellini uses the final scene of his final film to suggest that perhaps we ought to narrow our minds and return to simplicity.

This may be the crux of why gnocchi is the chosen dish – it’s simple, honest, and harks back to less frenzied times. Making potato dumplings by hand is a labour of love, an act which may seem ludicrous in this age, but, in spite of the insanity all around us, a love of good food can unite us all, more than the Catholic Church or lascivious press of Fellini’s fictionalised society. Leopardi’s The Waning of the Moon uses the comparison of the twilight years of one’s life to a Moonless night. Whilst Fellini’s protagonist is not near the end, the Moon shines as brightly as ever, he has nevertheless resigned himself to the knowledge that its voice will not be heard by everyone, and that his love is forlorn. Pasta is an earthly pleasure, accessible to all, but lunacy is a rare gift. Three years after the film’s release, Fellini, excessive in all aspects of life, would die due to complications from a heart attack.

‘And to the night that weighs on later years, By the decree of doom, As goal is given the silence of the tomb.’ -The Waning of the Moon, Giacomo Leopardi