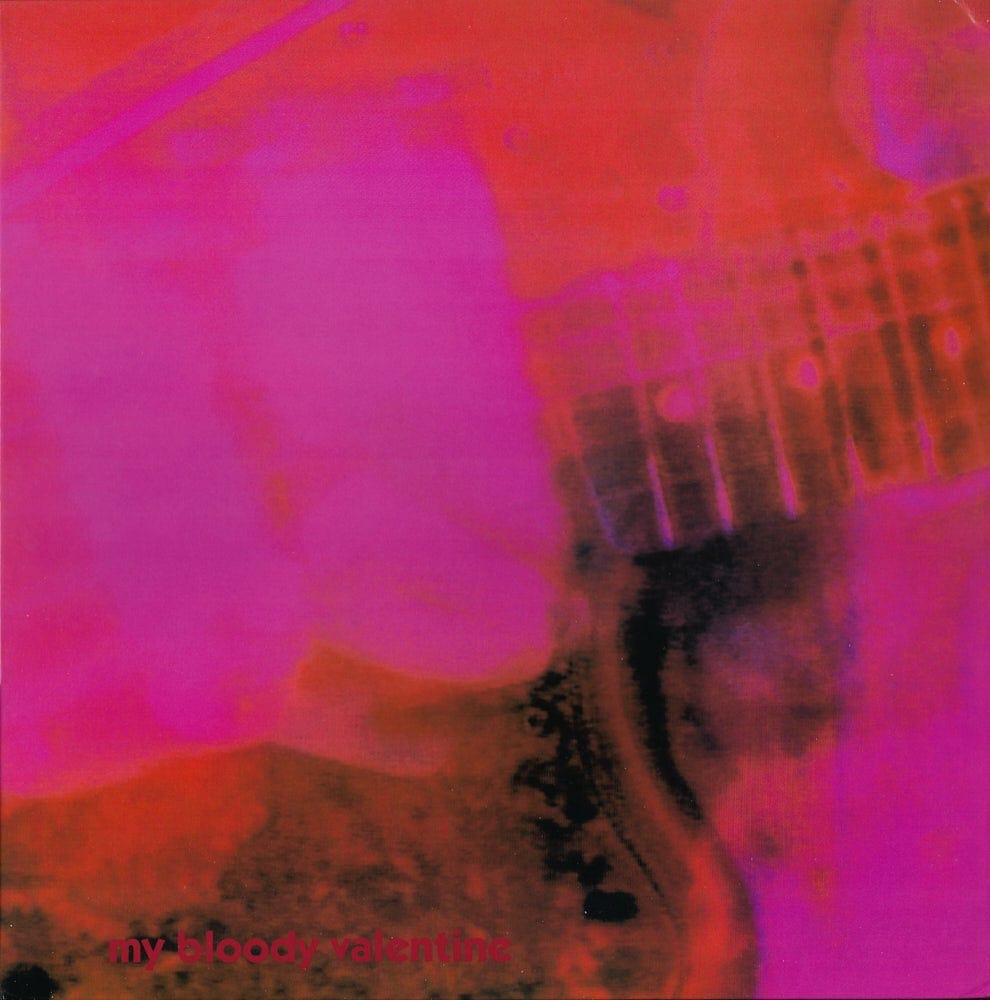

Still, 30 years on, nothing quite compares to My Bloody Valentine’s 1991 album, Loveless. The undisputed magnum opus of not only the band’s discography, but the shoegaze genre of rock, Loveless is a blissful fusion of distorted guitars, distant drums and deliberately disinterested vocals.

My Bloody Valentine at All Points West, 2009. Photo: Bryan Bedder

A sonic masterpiece, able to entertain you when doing nothing else – music that you can lie down and listen to for hours while staring at the ceiling – yet also the perfect soundtrack for the mundane everyday. As appropriate at 4am on a Wednesday as it is at 8am the following Thursday, Loveless is simultaneously all-consuming and white noise. Side-effects range from anywhere from existential helplessness to universal aplomb.

Now, 30 years on, it seems a good time to look back. Not least because the story behind the album I shamelessly slather in superlatives can help explain its magic, as well as why, perhaps, albums like Loveless are just so difficult to come by.

Loveless was not My Bloody Valentine’s debut. The band, who were signed to Alan McGee’s Creation Records, released Isn’t Anything in 1988, their first studio album coming on the heels of a series of EPs in the mid- to late- 80s. Isn’t Anything was a success – both critically and commercially. Perhaps most significantly, however – as Billy Holmes put it in these pages last week – the album “established the distinctive constructs of shoegaze.”

Though shoegaze was conceived from, and leant heavily on, pioneering artists like The Jesus and Mary Chains, the Cocteau Twins and A.R Kane, it was not until My Bloody Valentine’s Isn’t Anything that shoegaze itself was truly born.

In early 1989, work began on a follow up. Two EPs – 1990’s Glider and 1991’s Tremolo – immediately preceded Loveless, but still the three year span between the two albums was arduous, and My Bloody Valentine’s relationship with McGee and Creation soured. Largely because the band’s enigmatic frontman, Kevin Shields, was on a personal quest for perfection; or, as he repeatedly put it at the time, “I just want it to be decent.” Quite what this quest for perfection (or decency) entailed is now the subject of folklore: estimates of the number of studios and engineers range from 17 to 20, while the supposed cost of the 1991 album was as high as £250,000.

Despite the ever-changing personnel and the ever-increasing cost, Shields maintained that he was always in command of not only the record, but, crucially, himself. “I was pretty crazy, for sure, and it was a very manic, overdrive kind of state, but it never got out of control.” The furthest he supposedly fell was into a mere creative torpor: “I wouldn’t work. I wouldn’t get up till late afternoon. I watched a lot of shit films.”

McGee – “who was reduced to tearfully pleading with the musician to deliver the record before the whole enterprise went bankrupt” – disagreed. “[Shields] lost the plot completely. Everybody became the enemy. He lost his friends and he lost the band. He just locked himself away in his big house. I went once and there were chinchillas, these weird little rat animals, in cages, about 20 of them, all over the room, with barbed wire everywhere. It was definitely a meltdown.”

Kevin Shields performs at the 2009 All Points West Music Festival. Photo: Larry Busacca

Whatever the case with Shields and his rodent-canine hybrid creatures, he was motivated when in the studio. “Kevin really knew what was good quality and what he would and wouldn’t settle for,” said sound engineer Alan Moulder.

Accounts of the Loveless studio sessions depict a man who was utterly meticulous. From the freshness of the guitar strings to the placement of the amps to recording every track, top to bottom, at least three times, Shields orchestrated every microscopic detail of Loveless.

As the album’s production extended from weeks to months to years, Moulder came and went while working on other projects. “But I kept coming back because I liked working with [Shields],” he said in 2013. “It was long, weird hours, but being in a studio with Kevin is fun. Even if you are not working you are having an amazing conversation.”

Moulder’s almost transient involvement was possible because Loveless was created piece by piece – the band had already recorded most of the drums and rhythm guitars when he arrived in early 1990 – however the rest of the album existed only in Shields’ head. Interestingly, it was the lead vocals that arrived last of all. Amidst the overwhelming sound of Loveless, it is easy to overlook the gentle quality of the melodies. Though simple, and often quiet, the vocals are integral to the album’s unique emotional impact.

On November 4th 1991, Loveless arrived. Creation Records dropped My Bloody Valentine soon after. McGee went on to say that although he enjoyed the record, “we couldn’t bear the idea of going through that again, because there was just nothing to say that [Shields] wouldn’t do exactly the same.” He also cited Loveless as a reason behind is own, “personal meltdown,” and the album was often blamed for Creation Records’ financial struggles and eventual dissolution.

Shields, however, thought Loveless took the flack for Creation’s deeper issues. McGee’s personal struggles were exacerbated by his “drugs lifestyle,” and excessive spending on ambitious records was commonplace. “Creation had zero money,” Shields revealed in a 2012 interview with The Quietus. “They couldn’t pay our studio bills, so we had our tapes confiscated. That happened a lot…One night we were in some studio in Ladbroke Grove and we had to sneak them out in the middle of the night.”

These tales fuelled the intrigue in Loveless upon release. With speculation rife over just how expensive it had been and just how long it had taken, the resulting album was somehow not as weird as people were expecting. But then there was Kevin Shields himself, who’s eccentric nature saw him transformed into an almost mystical creature – a reputation only enhanced by the sonic void which followed Loveless. Because, though My Bloody Valentine signed a big deal with Island Records soon after leaving Creation, no album arrived.

In 1997, the band dispersed. For 22 years they released no new music. In this vacuum, both Shields and Loveless took on a life their own: Shields became the tortured genius, a victim of his own talent, who had been driven into insanity-ridden isolation in the big house on the hill; the album, meanwhile, was an innovative masterpiece, a totem of shoegaze and the 90s, but one which came at such extreme emotional and financial cost it could never be replicated.

These characterisations are not entirely true. Nor are they entirely false.

My Bloody Valentine

“I lost it,” Shields admitted to the Guardian in 2004 – then his first interview in 12 years. “I lost what I had and I thought, you know what? I’m not going to put a crap record out. But I wasn’t ready to move on. I reached a sort of stalemate with myself. I wanted to be where I used to be and have that powerful, strong sense of direction. But I wasn’t inspired.” More recently, in regard to the album and the band in general, he told NPR in 2018, “[Cutting and mixing] Loveless was a nightmare. It wasn’t supposed to take that long, it wasn’t supposed to be that hard, but this thing broke us in a way. It used all our money up and put us in a very not-good place.”

Conversely, the band recorded hours and hours of music after Loveless, but before their separation. Supposedly enough to fill two albums, and it was these recordings which laid the foundation for My Bloody Valentine’s reunion and 2013’s m b v – an album featuring material from both the mid 90s and the early 2010s. For Shields, personally, 2004 saw Lost In Translation. Sofia Coppola’s cult classic featured four of his original songs, as well the Loveless track ‘Sometimes’ – its numbing melancholy befitting of Coppola’s detached Tokyo.

But what of the album’s true legacy? Well, still it sits on a pedestal, still tantalisingly out of reach. Because, though it is not the only great shoegaze album, nor the only great My Bloody Valentine album, both the genre and the band soared to a height on Loveless that they’ve not been able to reach since.

There is no one reason why; no one quality which has rendered it untouchable. For at the very heart of the album’s magic is its duality. Between the noisy and the peaceful; between the tangible and the faint; the emotive and the numbing; the overwhelming and the okay. That’s why Loveless is as good tonight as it will be tomorrow morning. That’s why 30 years on, it’s still well worth celebrating, and will be for many more.