Jeremy Hunt was widely ridiculed last week for claiming that most Britons were desperate to get back to the ‘fizz’ and ‘excitement’ of office life. If there’s one positive to take from 2020 thus far, it’s that most of us have been spared the pain of witnessing its dizzying downs and more downs from our desks.

The reason the poor Hunt’s assertion elicited such widespread tittering is that office work is synonymous with the most extreme banalities of modern British life.

As someone who is himself very boring, Mr Hunt should probably be grateful for this. After all, it is our daily exposure to the almost nihilistically mundane that means we are often immured to, among other things, the sight and sound of people like him.

American Beauty (1999)

All Ricky Gervais had to do was call his show The Office for most people to understand the kind of environment he was satirising. One of the reasons it was so popular is because, until the pandemic, most people could expect to spend the majority of their lives working in an office.

So, office tedium, and the rich seam of office tedium-related humour, is one of the few cultural unifiers we have left in our increasingly fractured society. However, unlike partying, football or holidays, office work is a fact of life that British people endure rather than enjoy.

Much of the invective aimed at everyone’s favourite former health secretary focused on a standard office’s physical space. Commentators recalled the fizz and excitement of blocked toilets, instant coffee and nausea-inducing carpets.

Don McCullin, Steel Foundry, West Hartlepool

Their ridicule was well founded. For among the country’s square miles of post war concrete there are indeed hundreds of thousands of terrible offices. I, like many people of my not-that-advanced age, have known a fair few.

I’ve worked in some really grim offices. Ones with poor sanitation, electrical hazards, ancient technology and, in one case, a predatory office manager. I’ve also worked in several nicer spaces with comely pastoral bonuses such as free fruit, good art and space-age hand dryers.

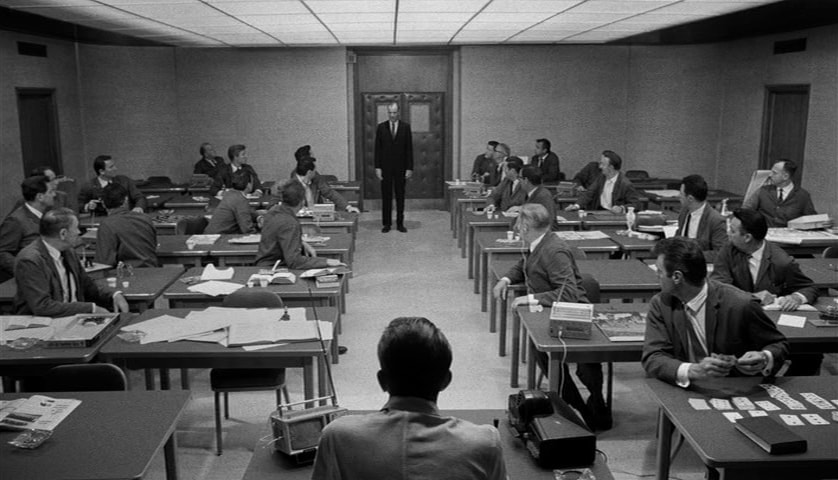

The Crowd (1928)

Looking back, many of the latter I associate with some of the darkest periods of my life, while one or two of the former I remember as transformative hothouses of creativity and lols. Despite the unpleasantness of working in a grim space, the most salient factor in our enjoyment of an office is always how fulfilling we find the work we are doing there.

The problem is, as this current debate has revealed, a significant proportion of us don’t find it very fulfilling at all.

I believe the reluctance of most people to return to their desks, notwithstanding the threat of contracting a deadly virus, as well as the usual heavy millstones of several hours’ commuting and sad Pret salads, is to do with the preponderance in the UK of what the late anthropologist David Graeber dubbed ‘bullshit jobs’. These are jobs which are generally well-paid and vaguely respectable but that confer no meaning or purpose on their holder—things like marketing or admin or corporate law.

ArrayAnother sign, Graeber said, of a bullshit job is the knowledge that were it to disappear tomorrow, it would have no discernibly negative impact on society, in fact (in the case of corporate lawyer) it might even make it better.

On the flipside, the pandemic has reaffirmed the importance of what Graeber called ‘bad jobs.’ Bad jobs aren’t bad because they aren’t useful or fulfilling but “because they’re hard or they have terrible conditions or the pay sucks.” Most, if not all, of the jobs done by key workers are ‘bad jobs.’

As Graeber said, “if we suddenly eliminated teachers or garbage collectors or construction workers or law enforcement, it would really matter… but if bullshit jobs go away, we’re no worse off.”

The Crowd (1928)

Of course, bullshit jobs are nothing new—there was probably some sort of ‘cave art PR coordinator’ operating in the Pleistocene Age—but in the past 40 or so years they have come to match, and maybe even supersede the number of both bad jobs and good jobs in the economy.

Reactionary politicians suggest that people aren’t returning to work because they prefer sitting at home in their pyjamas and doing nothing. Now, I’m no psychologist, but that sounds to me like pretty much the symptoms of terminal depression.

Of course people want to get back to work because it is the main thing, possibly with the exception of family, that gives meaning to our lives.

L.S. Lowry, Going To Work, 1943

We all want our lives to have meaning, at least while we’re living them. That’s the problem with bullshit jobs, they make it very hard to build up a sense of self-worth. I don’t think it’s a coincidence, as many studies have shown, that people in this country are on average less happy than their grandparent’s generation, many of whom lived through the darkest days of the 20th century.

Though its severity can be called into question, there’s near universal acknowledgement among our leaders that we will soon go through a period of mass unemployment. As is always the case, this will disproportionately affect young people.

there’s near universal acknowledgement among our leaders that we will soon go through a period of mass unemployment

Last year, a meme did the rounds that said, “I’m a millennial so my life goal is societal collapse.” As with all the greatest art, its power lay in its truth. The jobs market, especially in London, has become so saturated with bullshit that it’s become hard to imagine anything but a complete overhaul of the economy will restore young people’s hope in a better future.

Despite the pain and hardship awaiting us in the months ahead, this moment does offer an opportunity for real change. Our leaders must not waste it, especially if they want to see people return eagerly to office life.

Andreas Gursky, May Day V, 2006