Valve’s newly-launched Steam Deck reported very encouraging sales numbers last month and seems to possess all of the tools to be a thriving success in the hardware market. But then again, the Steam Deck won’t be the first handheld console that was touted as being just too great to fail…

There are many things that the world has taught us to be wary of. Beware the dog. Beware the Ides of March. Beware the Jabberwock, my son. That’s just a small selection of the near-infinite number of hazards that we should all aim to avoid in the name of self-preservation. But we know, above all else that the number one hazard to beware is that dastardly invisible danger that none of us ever seem to see coming:

The sure thing.

When Valve announced the Steam Deck last summer, the Linux portable gaming device seemed like the very definition of a sure thing. Longtime Steam users having access to hundreds of games from their library, all whilst on the move? Check. Players new to PC gaming acquiring an entry-level piece of hardware for $400? Check. A similar docking function to Nintendo’s popular Switch meaning the handheld can also double as a gaming unit for your home? Check, check, check.

On paper, at least, the Steam Deck looks like a proposition that is simply too good to fail and with its consumer rollout now ramping up in earnest, the numbers are looking good. Valve announced that throughout April, the handheld device was the #2 grossing product on the Steam store, outsold only by the monster RPG hit, Elden Ring. Valve President, Gabe Newell, told IGN last July that “If we’re doing this right, we’re going to be selling these in millions of units,” outlining the huge growth potential that the Steam Deck is seen by many to possess.

However, from the release of Atari’s E.T. all the way back in 1982, through to CD Projekt Red’s botched launch of Cyberpunk 2077 less than a year and a half ago, the decades-long history of video games is littered with ‘sure things’ that were seemingly destined for great success. Instead, many of these these projects have become bywords for grand hubristic failure, remembered not as flourishing triumphs, but rather as cautionary tales of the ills of corporate avarice, unpredictable market trends and flaws in hardware design.

This is especially true with regards to the mercurial nature of the portable gaming market which has tripped up some of the industry’s most successful hardware producers. Sega, Sony and even the handheld kings, Nintendo, have all come undone at one point or another whilst releasing portable gaming machines. With hindsight, it’s clear that some of these machines such as Nintendo’s infamous duffer, the Virtual Boy, were always destined to end up as little more than a punchline. However, there also are those handheld gaming machines that seemed like the surest of sure things. Then they hit the world and quickly faded into obscurity. Whilst we certainly hope that Valve’s Steam Deck doesn’t one day find itself on this list this list, join us as we look back on the handheld games devices that were too perfect to fail (and yet somehow still did).

Sega Nomad

Rewind back to America in 1995 and the Sega Nomad (sometimes also referred to as the Genesis Nomad) looked like a Sega fan’s dream come true. American gaming in the 1980s had been synonymous with Nintendo’s NES console, but with the dawn of the nineties, Sega had edged the US console market with their 16-bit Genesis console (known internationally as the Mega Drive). Despite having another key hardware manufacturer in the form of Atari CEO Jack Trammel (more on him later) decline to distribute the Genesis in North America, the system had flourished nonetheless, outselling its greatest rival, Nintendo’s Super NES by a two-to-one margin at one point.

As the Genesis came towards the tail-end of its life, Sega’s American operations had Nintendo on the back foot and keen to press its advantage, the company announced the release of the Nomad, a North American-only handheld gaming console that would allow gamers to play Genesis games on the go. Not only that but it was the only handheld device at the time that could be connected to a TV too, effectively giving you both a home and handheld console in one. Plus, it would release with an existing library of hundreds of Genesis titles already on the market.

It helped that Sega weren’t novices when it came to handheld gaming either. They’d already launched the Game Gear in 1990 to some success, seeing off rivals like the Atari Lynx and NEC TurboExpress but not putting much of a dent in the runaway sales of Nintendo’s technologically-inferior Game Boy. However, along with a short battery life, the Game Gear’s largely-uninspiring software had limited its ability to combat the Game Boy’s dominance. with the Nomad, Sega was arming their next handheld with the Genesis’ entire library of games, a formidable offering indeed.

The mid-90s were a time of strange technical experimentation from Sega and ironically, it would be the same spirit of innovation that would both birth and neuter the Nomad. Believing that technical superiority was the way to continue waging war on Nintendo, the company had already released the Sega CD and 32X peripherals, additions which boosted the performance of the Genesis. However, the Nomad wasn’t compatible with either and with Sega’s new console, the Saturn, emerging to do battle with the likes of Sony’s PlayStation and the Nintendo 64, the underpowered Nomad soon fell to the wayside. What’s more, Sega had never really solved the battery life issues that had plagued the Game Gear and as such, it only sold a fraction of the numbers its predecessor had managed.

If it had released earlier in the Genesis’ era of US console dominance, the Nomad may have been a handheld console to reckon with. After all, with its ‘sideways’ software compatibility allowing gamers to use their existing Genesis games, not to mention its TV connection capabilities, it was years ahead of its era. Timing they say, is everything and the Nomad was simply two or three years late to a market that was in considerable flux as it launched, consigning it to nothing more than a failure that under different circumstances, could have been so much more.

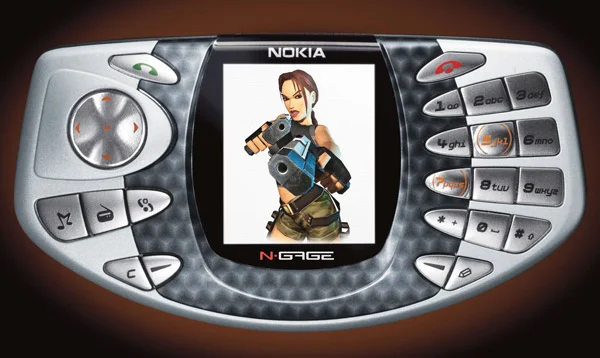

Nokia N-Gage

Sometimes, the greatest idea in the world can be undone, simply from a lack of due diligence. Here’s a tale that reminds us that being the first to market with a great idea doesn’t guarantee you success if your product is flawed. This was the harsh lesson that Nokia learned when they fluffed the opportunity to create a handheld consumer electronics device that, all hyperbole aside, had the potential to be as innovative as the iPod or even the iPhone. After all, let’s not forget that in 2003 when the N-Gage launched, Apple’s first generation iPhone was still some four years away. Meanwhile, Nokia were the biggest mobile phone manufacturer in the world and what’s more, the Finnish company had spied a gap in the market that had the potential to change the face of consumer electronics.

At the time, not only were most young people were carrying around mobile phones, plenty of them were also lugging around some kind of portable gaming device too, be that a Game Boy Advance or less likely, a Gizmodo (a handheld gaming device you won’t find on this list). Nokia saw a chance to combine both technologies giving consumers a single device on which they could both play games and communicate.

On paper at least, the concept was sound: big-name game publishers such as Sega, Activision and Eidos were signed up and the device itself posted a number of impressive technical features such as bluetooth wireless multiplayer and an on-board MP3 and video player. Most importantly though, Nokia were ahead of the the curve, sensing that gaming on mobile phones would be the future long before most of their rivals. Too far ahead of the curve it proved, when the N-Gage launched to poor sales and no small amount of ridicule for the awkward way in which it had to be physically positioned to receive phone calls.

The convergence between mobile phones and games would come, but Nokia’s aims of dominating that billion-dollar market would never come to fruition. In retrospect, their mistake was clear. In directly taking on Nintendo for the ‘hardcore gamer market’ with titles like Tomb Raider and Sega Rally, the company was crossing swords with a long-established industry titan that had previously vanquished far more experienced rivals than Nokia. Nintendo’s Game Boy Advance, a handheld console with legendary brand recognition could be purchased for $100, whilst Nokia’s N-Gage, the new kid on the block was retailing for a whopping $300.

The mobile gaming revolution would come, but it would instead be ‘casual’ gamers that would form the majority of this huge new market. With their simple touchscreen controls and gatekeeper-style app stores, the first generation of modern smartphones were perfectly positioned to profit from this largely untapped market. By that point, the N-Gage brand had become nothing more than the name of the Nokia’s mobile games platform which featured on their range of increasingly unpopular mobile phones. With better research and design, the original N-Gage could have set the world alight. Instead, it died with barely a whimper.

Atari Lynx II

The Atari Lynx II was launched in 1991 and as the numbering suggests, was Atari’s second stab at handheld console dominance in what was becoming an increasingly contested marketplace. The Atari Corporation that had produced the first Lynx was not the same Atari that had enjoyed market saturation in American homes with their wildly popular VCS consoles in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

This version of Atari had been launched in 1984 by Jack Tramiel, the founder of Commodore. The company launched an ambitious plan to attack the video games market on all fronts with a range of Atari-branded products: Their home computer, the Atari ST launched in the mid-1980s and did lots of other things as well as play computer games. Atari’s dedicated home games console, the Panther was aborted shortly before launch, supposedly due to fears it would be technologically inferior to its competitors, whilst Atari’s assault on the handheld market had commenced with the first Lynx, launched in 1989.

Atari’s debut effort into the portable console market had made a solid dent, selling half a million units in 1990. Its custom16-bit graphics processing chip and full colour screen offered a graphical fidelity that Nintendo’s recently released Game Boy couldn’t hope to match. However, at a lower price point and with a library of beloved franchises such as Super Mario, Metroid and Tetris, the Game Boy had shifted around nine million units in the same era. This would spawn a trend of Nintendo outfoxing its technologically-superior rivals with innovative products that continues, on and off to this very day.

However, with the launch of Lynx II, Atari were confident that their significantly-lower $99 price point, along with a new marketing blitz, plus a slate of games including Batman Returns would see them stake a bigger share of the handheld market. The Lynx II was also noticeably smaller than its predecessor, packed stereo sound, a clearer screen and better battery life into its redesign, but as its place on this list attests, it would not be enough. The Lynx’s impressive new features simply couldn’t challenge the monstrous share of the market that Nintendo had carved out with the Game Boy, something that NEC and Sega would learn to their chagrin when they too released handhelds with more advanced features that would also fail to unseat Nintendo.

If Atari had gotten all of the Lynx II’s features into its predecessor at that $99 price point (rather than the original $179 cost), things could have gone differently. Even then though, it’s an oft-quoted rule that hardware is always defined by its software and the Atari Corporation simply didn’t have the same back catalogue of beloved titles to mine as Nintendo. Whilst the earlier incarnation of Atari boasted some classic titles such as Pong or Adventure, the newer version of the company never really managed to create any classic or memorable first-party titles. By 1993 Atari had all but exited the handheld market and within three years had both launched and discontinued its commercially-disastrous home console, the Atari Jaguar. The mingled release of that console would effectively lead to Atari’s demise as a meaningful player as a hardware developer.

Steam Machine

It’s easy to pin a lot of the issues above on the ineptitude of the manufacturers. After all, Sega, Nokia and Atari are all united by the fact that poor management led to disastrous console launches, where each company overextended themselves by seeking a greater slice of the handheld market. Within four years of the botched releases detailed above, each company would permanently exit the hardware market. Valve, the manufacturer of the Steam Deck are clearly not a company in decline. Their online games store, Steam is the world’s biggest PC gaming platform and the company earns, on average a 30% slice of every game sold. Unlike the companies above, all of which exited the hardware market following some questionable choices in direction, Valve’s business acumen is clear. For example, its recent decision to ban NFTs from its Steam platform is yet another signal that the company is continuing to take a long-view approach to protecting the industry’s health rather than simply seeking short-term financial gain.

However, when it comes to the volatile handheld market, even Valve have tried and failed to leverage the considerable resources at their disposal into a successful portable gaming device. Rewind back to 2015 and the company announced a range of ‘Steam Machines’ produced by either Valve or by licensed third parties, home gaming PCs that were available in a range of specs and prices. The planned handheld Steam Machine, known as the Smach Z looked to have all of the necessary tools to make a splash in the portable market: a HD LCD screen, haptic touchpads, five hour battery life, a quad-core AMD processor and like its eventual successor, the Steam Deck, a Linux-based operating system.

Whilst the Smach Z Steam Machine was always going to face steep competition from the likes of the Nintendo Switch and the increasingly impressive array of software available on smartphones, its ability to give users portable access to PC games, many of which Steam users already owned in their Steam libraries was its obvious selling point. Over the course of two successful Kickstarter campaigns, Smach raised over a million dollars in backing and things looked promising. Then came four long years of development problems during which Valve likely began to regret licensing the Steam Machine brand (and by extension, Valve’s own reputation,) to companies who were struggling to create quality gaming hardware, or in the case of Smach, even get their product to market.

The Smach Z would never see the light of day, with various promised reveals never happening. At the same time, Valve’s entire Steam Machine experiment was slowly unravelling with even their in-house produced flagship gaming rig failing to sell in any meaningful way. The failure of Valve’s Steam Machine line would be a huge factor in influencing their decision to produce the Steam Deck internally, with the handheld console’s designer telling IGN in July 2021 that “more and more it just became kind of clear, the more of this we are doing internally, the more we can kind of make a complete package.”

Falling short of greatness often means nothing less than total extinction.

Whether the Steam Deck will be that ‘complete package’ remains to be seen, but the early signs are good. Still, with smartphone gaming still thriving, the Nintendo Switch recently getting an OLED screen upgrade, not to mention competition from lots of other smaller handheld manufacturers, the portable gaming market is as difficult to predict in 2022 as it was in 1992.

Unlike the devices detailed above, we hope the Steam Deck sticks around and along with the Switch, sparks a second Golden Age of handheld gaming. As for the others, their legacy will be to live on in articles like this, proving the cruel rule of video game hardware design: it’s a precipitous tightrope, and falling short of greatness often means nothing less than total extinction.