Rory Doherty explores the ways two acclaimed British directors, Steve McQueen and Jonathan Glazer, create parallels between the horrors of the Nazi regime and the rise of fascism in Britain in their films Occupied City and The Zone of Interest.

There has always been fertile ground for fascism to grow in Britain. While some are quick to remind us that the original UK fascist movement was quashed by the outbreak of WW2, we are no exception to the recent, unignorable global spread of far-right beliefs, and have recently seen our government attempt to restrict our right to protest, the rise in hate crimes, and regular public demonstrations of organised bigotry (which are, thankfully, usually greeted by way more counter-protesters). Politicians have been more outspoken on catering to voters tempted by fascist ideals like brute force and white dominance, leading two celebrated British filmmakers back to the source of most modern fascist movements – the horrors committed by the Nazis.

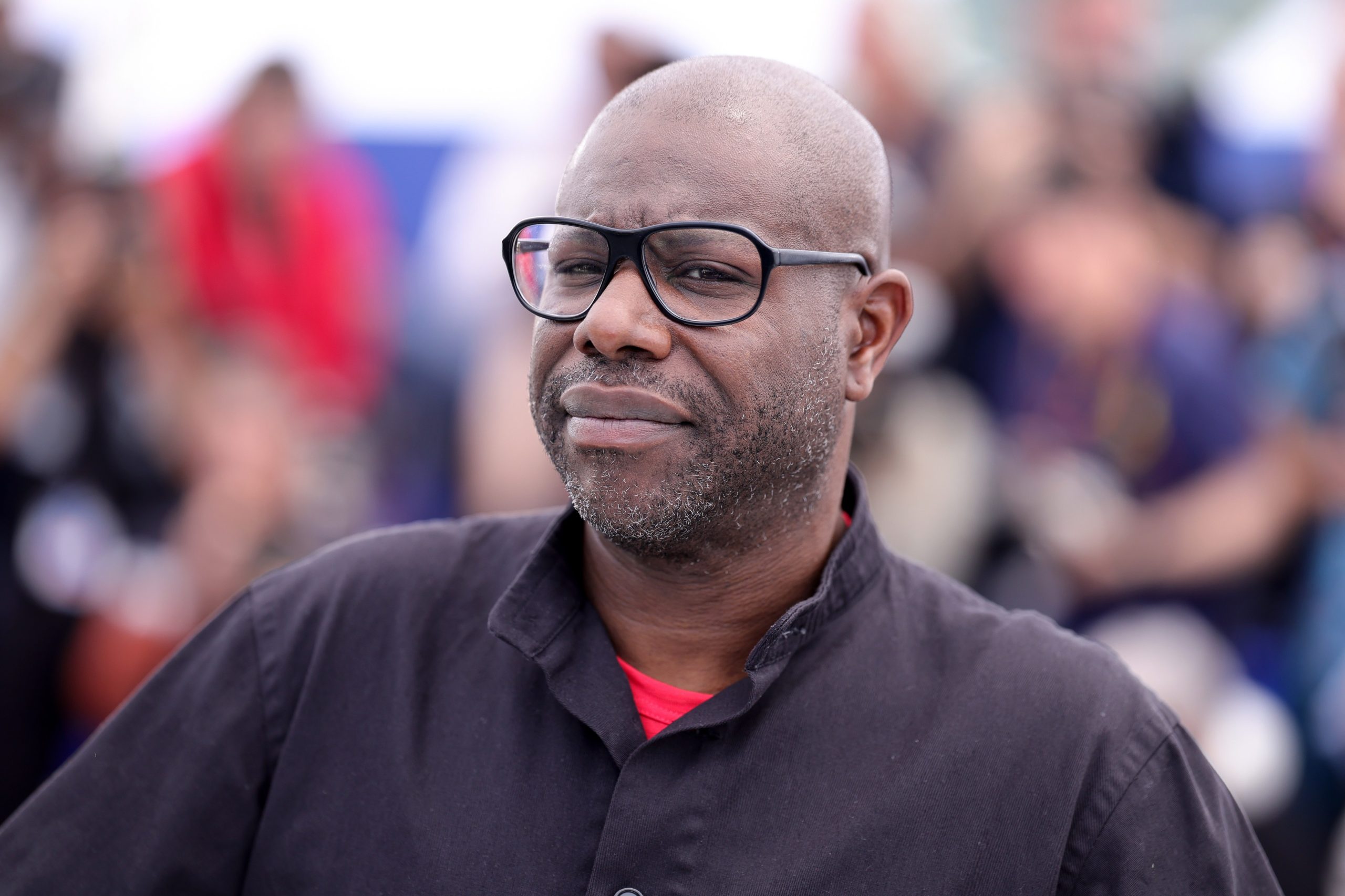

Steve McQueen, director of Hunger, 12 Years a Slave, and BBC’s anthology on Black Britain Small Axe, has made a career out of forcing us to look at what is unpleasant, but a fact of history. His camera rests on acts of brutality or markers of institutional abuse, and we are given no choice but to watch until he says we’ve seen enough. His latest film, Occupied City, a four hour plus documentary mapping out the sites of Nazi terror across their five year occupation of Amsterdam, speaks in a very similar language.

But instead of showing us the violence suffered from 1940-1945, the film consists of B-roll of modern Amsterdam, with voiceover artist Melanie Hyams describing what happened in each spot 80 years ago. It might sound like a punishing watch, but Occupied City’s rigorous archiving spreads into a powerful testimony on how invisible all of Amsterdam’s trauma is today.

Steve McQueen’s Occupied City. Credit: Film4

If Occupied City is about what pain remains from the Nazi regime, The Zone of Interest argues that most Nazis weren’t even looking while it was being inflicted. Director Jonathan Glazer made a name for himself with intensely stylised and subversive genre tales – and also for making them so infrequently. With their upsetting visuals and entrancing soundscapes, Sexy Beast, Birth and Under the Skin could be classified as Psychological Warfare Cinema, something that’s jacked up to eleven in his latest film, which follows the impossibly normal activities of a Nazi commandant’s family living in the literal shadow of Auschwitz.

Occupied City makes us imagine atrocities happening on the very normal, modern streets we’re being shown; The Zone of Interest forces us to acknowledge the darkest extent of Nazi ideology happening – look! – right in front of us. The tension comes from the Nazi family failing to acknowledge anything evil about the life they’re enjoying – we watch for 100 minutes what it’s like for humans to live without a conscience, without their behaviour being altered in the slightest.

Of course, neither McQueen nor Glazer’s films are set in the UK. The Netherlands, McQueen’s home for the past 27 years, has its own extensive history suffering under fascist rule, and Poland was not just the first country occupied by the Nazi party, but the centrepiece for the worst genocide ever committed (The Zone of Interest is also in German).

The Zone of Interest. Credit: A24

To think of these films first and foremost as commentary on the political state of our nation, one that consistently centres itself in international narratives, reduces the creative and historical curiosity shown by the filmmakers and sidelines the suffering of non-English-speaking nations.

But no story of fascism exists in isolation, and both films not only remind us of Britain’s past and present with regressive politics, but challenge its usual, tired perspective on fascism in Europe. There are no Brits, nor references to British history, but the films certainly want to implicate Britain and its famous complacency about calling out ugly politics. The methodical, unceremonious ways they lay out the everyday violence of the Nazis makes it clear that any country could be infected with fascism.

After a joint victory in WW2, Britain likes to think of Nazis as this distinct, separate, and therefore incomparable power that we should never reference or analyse ourselves to. This is apparently to avoid disrespecting Nazi victims, but all it does is revise and ignore history.

Take the controversy surrounding Gary Lineker’s recent critique of the UK government, we saw a widespread, aggressive resistance to considering ourselves as history’s biggest monster – largely to avoid the very true fact that banning protests, penalising immigrants and refugees, and whipping up hatred towards queer people are high up on the list of “things a fascist society does”.

(L-R) Christian Friedel, Director Jonathan Glazer and Sandra Hüller attend “The Zone of Interest” photocall at the 76th annual Cannes film festival at Palais des Festivals on May 20, 2023 in Cannes, France. (Photo by Mike Coppola/Getty Images)

Occupied City and The Zone of Interest shatter this uniquely British fallacy, shedding light on not just the normalcy of Nazi power, but how eager many were to collaborate in its regime. The Nazis were monsters, but didn’t operate like cackling villains; their rise to power and wartime expansion was managed with a bureaucratic, organised efficiency that can be replicated anywhere.

In one moment in The Zone of Interest, we see a bird’s eye view of a Nazi meeting of about two dozen concentration camp commandants. You think, “If only someone dropped a bomb on this room…” before realising that this wouldn’t stop the Holocaust, anti-semitism, or Nazi power. Others would be promoted, the bureaucracy would strengthen itself, the sickness would keep spreading. It’s what happens when you make an idea institutional; its power lies above individual players.

After only three screenings, Occupied City has already worked up a bit of controversy; a sequence showing a gathering of anti-lockdown protestors (Occupied City was shot throughout the pandemic) with narration describing the punishing conditions of Nazi occupation has some critics slamming McQueen for comparing government handlings of a pandemic to Nazi policies. It’s bold at any time to presume the motivations of a filmmaker, especially in a film that plays with such bold visual/audio juxtapositions like Occupied City, and such a complaint misses McQueen’s likely point.

Instead of thinking about how similar these two moments in Dutch history are, wouldn’t McQueen want us to think about how different they are? What’s more, anti-lockdown protests across the Netherlands, Germany, and even Britain commonly cited the need to resist Nazi-esque dictatorships during the pandemic; by comparing the two moments in Dutch history, McQueen reveals how insubstantial the argument is (a lot of these protestors expressed right-wing views anyway).

Occupied City. Credit: Film4

Fascism affects the psychology of its people long after its leaders have been overthrown, an invisible stain that lies beneath, above, and inside the walls of a nation, never really going away and not announcing itself with pomp and circumstance when it returns. There are still Nazis, there is still anti-semitism, and waves of people are seduced by the idea of a world enforced by ruthless order, violence, and bigotry.

Occupied City and The Zone of Interest could only be made at this moment, a strange in-between state for Britain where fascism has never been so visible but its presence being so denied. Living in Britain, and watching McQueen and Glazer’s films, is like living in The Truman Show: no matter how clear the evidence is that something is terribly wrong around us, everyone has been trained to never admit it.

The films give us the tools for analysing the machinery of the Nazis and leaves us with the terrifying notion that if we used the same analysis on our own country, we would also find something horrible. These are not films about Britain, but for these two filmmakers, Britain lives in every scene, every frame, every cut, everywhere evil is given room to root itself.