Wu-Tang Clan redefined hip hop in the early 90s. With plenty of time to kill, Sammi Gale turns his attention to the kitschy kung fu films and niche religious ideology that inspired the music of a generation.

Back at university, a group of guys would get together and watch the old kung fu films that inspired hip-hop collective Wu-Tang Clan. I wanted to fit in, so I went along.

Mainly I remember farcical dubbing and the constant kitschy sound of swords clinking. But, revisiting these films again in lockdown, I’ve been wondering, why were these rappers from Staten Island so obsessed with kung fu films in the first place?

No world is as combative and expansive as Wu-Tang Clan’s. Growing up in Staten Island during New York’s most turbulent times (and in violent, poverty-stricken neighbourhoods), the hip hop group found solace in an unlikely source: Kung Fu movies.

Themes of discipline, honour and brotherhood proved fertile material for a group of young boys navigating chaotic surroundings.

Fitting, then, that ‘Shaolin’(one of the oldest, largest, and most famous schools of kung fu) is the very first word on their game-changing debut album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) (1993). The group applied the name ‘Shaolin’ to their hometown.

‘I realised that Shaolin was the foundation of Wu-Tang,’ writes founding member RZA in The Wu-Tang Manual. ‘Shaolin is your mind and Wu-Tang is your body. You could be Wu-Tang, and Shaolin is where you come from. That’s why I named Staten Island Shaolin.’

ArrayThe Wu-Tang Manual is a testament to the group’s virtuosic merchandising as much as to its sweeping mythos, which combines religious jargon, apocalyptic mysticism, and kung-fu-fuelled fantasy.

I can’t think of many hip-hop collectives that would require such a manual, still fewer bold enough to follow it up with a second philosophical book, Tao of Wu.

These satellite texts appear part of a total aesthetic, entering the marketplace amongst more conventional offerings: Wu-Tang comic books, cologne, and console games — and alongside the storied album Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, limited to a single copy that sold for $2 million in 2015.

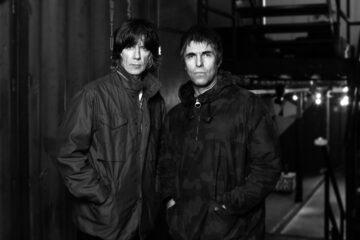

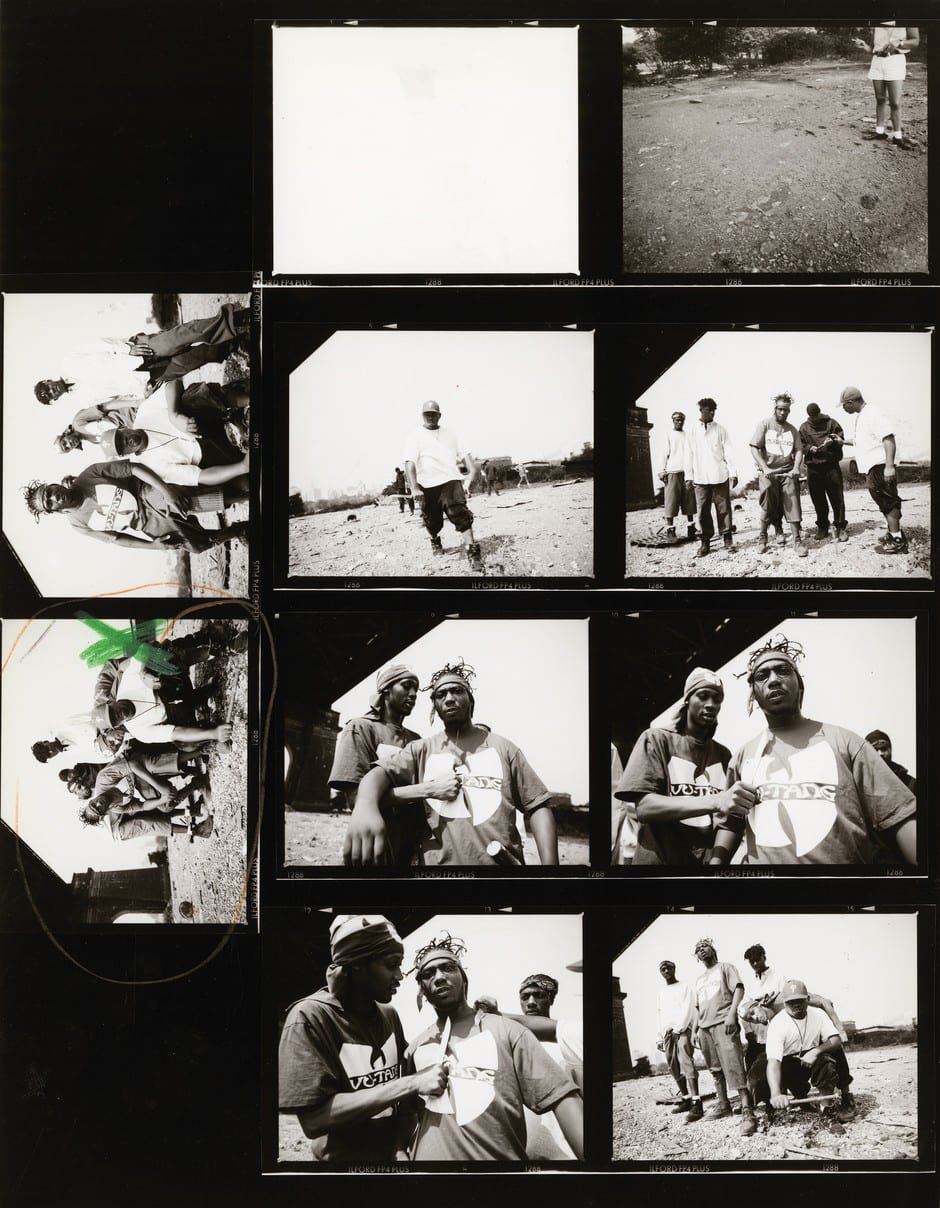

Photo by Danny Hastings, Courtesy of Sony Music

‘What’s your ultimate goal in this industry?’ asks an interviewer during an Intermission on Enter the Wu-Tang. ‘Domination,’ clan member Method Man replies. The fact that Wu-Tang Clan achieved this is hard to argue with.

‘FROM THE SLUMS OF SHAOLIN, WU-TANG STRIKES AGAIN’ – Method Man

According to Method, Wu is the sound of a sword slashing through the air. Tang is its collision with a shield. The title Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) is a mash-up of three kung-fu films: Enter the Dragon (1973), The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978), Shaolin and Wu Tang (1983). The album begins with a grainy sample from the latter:

Shaolin shadow-boxing and the Wu-Tang sword… If what you say is true, the Shaolin and the Wu-Tang could be dangerous. Do you think your Wu-Tang sword can defeat me?

The bad dubbing continues with a sample from Chang Cheh’s Ten Tigers of Kwangtung (1979): ‘En garde, I’ll let you try my Wu-Tang style’. Then blades clashing — a sound the foley artist might have made with keys or a shower curtain.

The beat, when it kicks in, is raw, the snare reportedly recorded in an elevator shaft, erasing any previous hint of melodrama, with RZA shouting ‘Bring da motherfuckin’ ruckus’ — a challenge of his own.

When RZA and Ol’ Dirty Bastard (fellow WTC member) were teenagers, they’d go to 42nd Street to watch kung fu films — hundreds of which were hitting the local cinema each year.

They would leave the theatre, do some kung fu fighting, then get on a train, keep fighting, before running into MCs and getting into rap battles. Here, after the old biblical adage, the tongue is a sword (‘Redrum, I verbally assault with the tongue’ goes one of RZA’s lines later in ‘Bring da Ruckus’; his lyrics do tend to hit you in retrospect, like the word ‘murder’ glimpsed in a mirror.)

DO YOU KNOW KUNG FU OR ARE YOU JUST A 42ND STREET BLACK BELT?

Kung fu fever was sweeping New York. Bill Landis and Michelle Clifford recall ‘it wasn’t unusual to see a dude decked out in an entire black belt’s outfit, holding lethal silver balls and num-chuks. As you walked down 42nd Street, you could often hear Carl Douglas’s one-hit wonder song “Kung Fu Fighting” booming from ghetto blasters.’

In particular, according to film scholar David Desser, African Americans’ interest in kung fu films ‘was a major factor in keeping the kung fu craze alive.’

Reasoning that, besides blaxploitation films, kung fu movies were the only genre with non-white heroes and heroines, he also points out the genre’s concern with an ‘underdog of colour, often fighting against the colonialist enemies.’

Whether or not Wu-Tang Clan members were watching kung fu films for their commentary on societal structures of domination and resistance, what seems clear is that the Clan selected specific kung fu films to develop their self-conception and worldview.

The 36th Chamber provides ‘discipline and struggle’, RZA explains, while Shaolin and Wu Tang gives ‘the virtuosity, the invincible style and technique — plus, the idea that sometimes the bad guys are the illest. And from Eight Diagram Pole Fighter, you get the brotherhood, the soul.”

Ultimately, the idea of ‘Shaolin’ becomes a way to transform Staten Island, ‘the crime side, the New York Times side’ (so sings Raekwon on the group’s song C.R.E.A.M.) where there are ‘stuck-up kids, corrupt cops, and crack rocks’ (a line from Inspectah Deck) — a mythological alternative to endemic violence, crime and poverty in the projects. ‘Wu-Tang sword style’ and lyrical violence is likewise an alternative to the very real violence in a Gambino-crime-family-controlled Staten Island during the crack epidemic in the late 80s and early 90s.

ArrayThroughout Enter the Wu-Tang, however, Shaolin melts in and out of view, swords traded for ‘glocks’ and ‘gats’, and ‘chamber’ referring to the barrel of a gun. Shaolin is a world coming into being; as RZA says, a state of mind.

For all its complexity, there does emerge a common thread between Wu-Tang Clan’s disparate influences: mastery. Five Percent ideology, with which the Wu Tang Manual is overflowing, teaches that Supreme Mathematics and Supreme Alphabet are a set of principles key to understanding humankind’s relationship to the universe (when Raekwon describes ‘Thoughts that bomb shit like math’, he isn’t talking about your times tables.)

Take chess, as another example: ‘The game of chess is like a sword fight,’ goes a sample taken from Wu-Tang Clan’s song ‘Da Mystery of Chessboxin’’ (named after a 1987 kung fu film). ‘You must think first, before you move’.

The elegant casing for Wu-Tang Clan’s single copy album ‘Once Upon A Time In Shaolin’.

The Wu-Tang Clan’s weaving together of myths has something of Adorno and Horkheimmer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment about it (‘myth is already enlightenment; and enlightenment reverts to mythology’). The theorists describe Odysseus’ cunning in duping the Cyclops Polyphemus by introducing himself as Nobody.

When Polyphemus cries out that ‘Nobody is attacking him’, his companions don’t come to his aid. Smart – but sustainable?

Adorno and Horkheimmer suggest that, having duped the more powerful with a weapon as light as language, Odysseus ‘is driven objectively by the fear that, if he does not constantly uphold the fragile advantage the word has over violence, this advantage will be withdrawn by violence’. Basically, he might have gotten away with it this time – but physical threat isn’t so easy to disarm as the slow brain behind it.

RZA, 1995. Photo by Michael Ochs.

It’s as if Wu-Tang Clan are involved in this process of losing themselves in the world of myth, thereby critiquing the tyranny which Nixon’s policies imposed – in the name of enlightenment, of course. That unforgiving worldview sees violence where it wants to find it; something which must be tamed into ‘discipline’ and ‘virtuosity’. As Ghostface Killah raps on ‘Bring Da Ruckus’ ‘I master the trick just like Nixon / Causin’ terror, quick damage your whole era’.

No wonder the revenge fantasies of kung fu appealed. In The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter, a Buddhist monk must exact revenge following the death of his family; the Clan seem to promise retaliation for the economic damage and judicial repression imposed on an entire generation. Inspectah Deck spent time in prison during the Nixon-era War on Drugs. Later, he sings ‘But as the world turned I learned life is hell / Livin’ in the world no different from a cell’; Staten Island is just a different kind of prison. At least Shaolin had rules.

–

Full width illustrations are from Map of the Wu-Tang Clan’s Staten Island, as described by the group’s co-founder, RZA and illustrated by artist Peach Tao, for the book Nonstrop Metropolis – a New York City atlas, edited by Rebecca Solnit and Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, published by University of California Press.