As Sudan become the latest nation to demand repatriation of valuable objects, Alexander Adams looks at some other claims have been made for artefacts in British museums.

Sudan has joined the list of countries seeking return of artefacts that are claimed to have been taken illegally. Museum officials are seeking to take possession of Sudanese artefacts in the British museums removed to the UK after the battle of Omdurman, during the colonial military campaign of 1896-8.

Artefacts include: two skulls (Edinburgh Anatomical Museum), a military banner (Durham University Palace Green Library), armour (National Armouries Museum, Leeds) and weapons (not identified, but which may include a sword and scabbard at Reading Museum). Curator Ahmed Mohammed said, “I want to show the real detail of the battle of Omdurman and I cannot do that without all the items. It is very important for the Sudanese people to know.”

1945: ‘Operation Elgin’ is carried out – 100 tons of priceless Elgin marbles are moved from their wartime hideout in Aldwych Tube to the British Museum, London. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

So far, the museums have not committed to take any action.

Five other outstanding claims against British museums include:

1. The Elgin Marbles/Parthenon sculptures, British Museum

A frieze which forms part of the ‘Elgin Marbles’, taken from the Parthenon in Athens, Greece almost two hundred years ago by the British aristocrat, the Earl of Elgin

Acquired from the Parthenon, Athens under unclear circumstances by the Earl of Elgin between 1801 and 1812, these sculptures (created 447-438 BC) are considered the high point of classical Greek civilisation. They are viewed as a national treasure by both the British and the Greeks. Elgin claimed he saved the decorative statues from destruction. The Parthenon was used as a gunpowder store by the occupying Ottoman Empire at the time, with statues used for target practice. The Christian Greeks were not then as protective of these pagan idols as they are now.

The British Museum (backed by the British Government) has always rejected the request to return the statues. Legally, the museum cannot give away, sell or destroy objects in its permanent collection. This is called “deaccessioning” and in the case of national museums, it is prevented by law.

2. The Benin Bronzes, various museums worldwide

Benin Bronze statue in Glasgow Museum

The 1897 Benin Expedition of British armed forces in the West African Kingdom of Benin led to looting and confiscation of artefacts from the king’s palace. The most notable acquisitions by the British were the Benin Bronzes, a collection of important figure sculptures, made between 1550 and 1750. Exposure to these changed European attitudes to African culture and forced scholars to admit that Benin had sophisticated technology and a rich artistic tradition.

Some bronzes have since been sent (or sold) to West Africa. Return of the bronzes is highly controversial, not least because of the difficult relationship between Benin and Nigeria. Nigeria has bought bronzes from museums and there are disputed claims between the countries as to where the bronzes should be displayed. The state of Benin does not include the Benin territory where the king’s palace was sited, which is now part of Nigeria. The manufacture, provenance and ownership of the bronzes is controversial to this day.

3. Cyrus Cylinder, British Museum

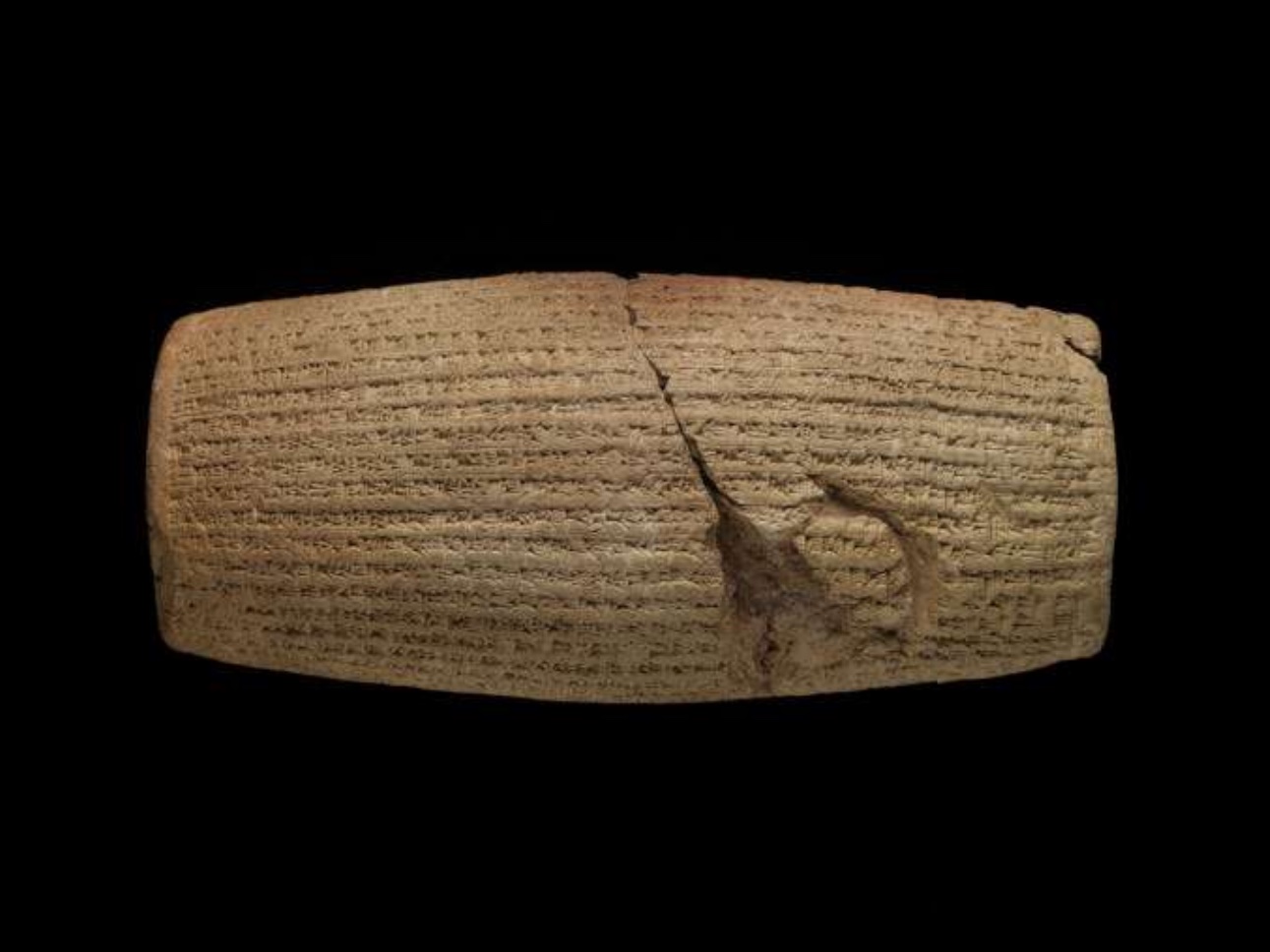

The Cyrus cylinder: clay cylinder; a Babylonian account of the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus in 539 BC

This baked clay cylinder is inscribed with the laws of Cyrus, King of Persia, made in the 8th century BC. It was discovered in the ruins of Bablyon and taken to the British Museum. The laws set out the principles of the kingdom. It could be rolled across slabs of wet clay to produce copies. As such, it is perhaps the earliest form of printing.

Although it was found in Babylon (Bagdad), in the territory of modern Iraq, the cylinder is claimed by Iran. Naturally, the question arises does the artefact properly belong to the British (who found it), the Iranians (whose ancestors made it) or the Iraqis (on whose territory it was found).

4. Easter Island statue, British Museum

Easter Island Statue in the British Museum

The giant 2.4m-tall statue carved from volcanic basalt rock was made around 1200 AD by the occupants of the remote Easter Island. The series of famous statues were part of the culture’s ancestor worship. The culture collapsed shortly before the first European explorers arrived. It was taken to London in 1869.

In 2019, the ancestors of the carvers requested the return of the statue. One representative said “England people have our soul. And it is the right time to maybe send us back (the statue) for a while, so our sons can see it as I can see it. You have kept him for 150 years, just give us some months, and we can have it (on Easter Island).”

5. Ethiopian tabots, various locations

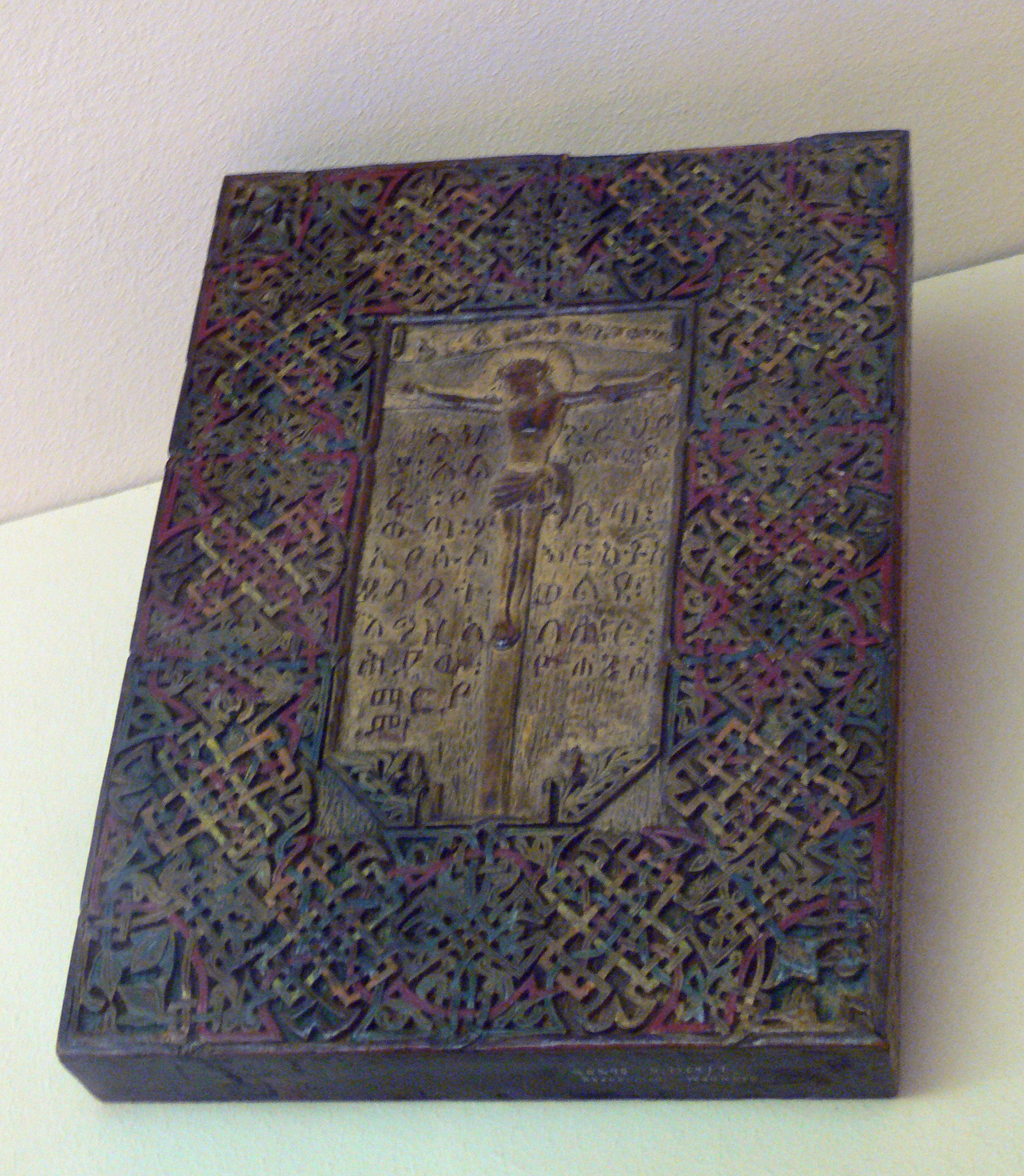

An Ethiopian tabot at the Linden-Museum in Stuttgart

One of the results of the 1868 Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia) expedition by the British resulted in the looting of many sacred tabots. A tabot is a tablet with the Christian Commandments inscribed on it. Some of the are elaborate and made with precious materials. The dispersal of these throughout Britain, including to the British Museum, has caused difficulty tracing them. Some have been returned to Ethiopia.

While many British curators and historians have reservations about deaccessioning, the Museums Association does not. It was founded to maintain ethical standards for museum staff. In recent years it has heavily backed efforts to deaccession and decolonise museums.

The difficulty national museums in the UK face is that if legislation were passed to permit deaccessioning, this would open a wave of claims. Populist politicians and ambitious museum directors from former colonies would make multiple claims against British institutions. Who would adjudicate these claims, in a field where everyone has a political and ideological agenda?

As explained in a 2018 article, transfer of ownership of museum artefacts could lead to further injustices. The decolonisation-and-restitution road is more complicated and ethically contentious than supporters imagine.

2 Comments

Mr Adams, I subscribed only to tell you that your article is nauseating, those articles you mention were stolen, they were never created or intended to be at the UK and therefore there’s no reason to hold onto those besides blatant cynicism, there are plenty of cultural artifacts at the UK to fill museums, holding on stolen ones just shows the worst part of your people.

i also subscribed to tell mr adams his article is nauseating. the british government created that law because they didn’t want to give back the stuff! obviously. everything acquired was as legal as was nazism in germany and slavery in the us. grow up.