Two-thirds of the way through the year 2020, one thing seems clear: the year’s major technological event has been the rise of the Zoom call. Between December and April, average daily users of the service rose from 10 million to 300 million.

Of course, there had been Skype and FaceTime before, but neither had quite supplanted the enduring popularity of the voice call. Now, video calling is suddenly commonplace. More than that, it has become tedious. Friends talk about Zoom (often over Zoom) with an accompanying eye-roll, and the word has become a byword for workaday drudgery.

It’s a scene of high-drama and, as such, is quite unlike many Zoom calls today.

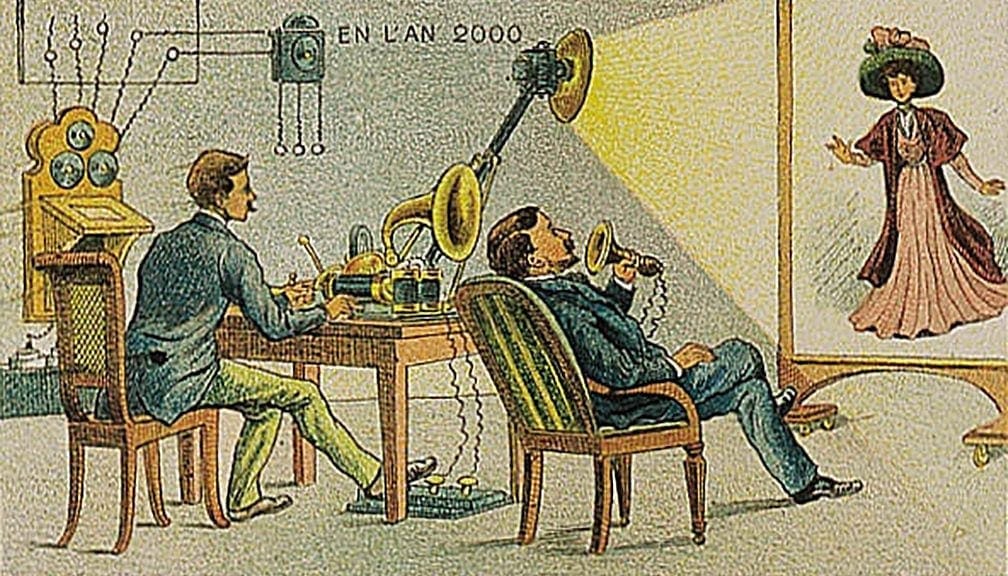

But take a look at the video call in the historical imagination and its sudden banality appears surprising. For over a century, videotelephony, as it was once known, was an image of a world yet to come.

A scene in Fritz Lang’s 1927 epic, Metropolis features the first video call in film. A wall-mounted videophone the size of a phone-box connects the subterranean worker’s city with the wealthy owners above ground, and serves as the medium for a heated argument about whether to let a group of rioting workers through the gates and risk flooding the worker’s city. It’s a scene of high-drama and, as such, is quite unlike many Zoom calls today.

ArrayA more accurate depiction can be found in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, where Dr Haywood Floyd takes a break from the daily routines of space travel to make a quick video call to earth. Floyd’s young daughter appears on the monitor and asks him if he will be there for her birthday. He tells her he can’t be, wishes her a happy birthday, and says goodbye. Remarkable is the way the scene anticipates the banality of video calling. There is something sad about it, too. It reminds me of the video calls of today, with loved ones in different countries whose digitised images make them feel not closer but further away.

Kubrick’s film was released shortly before a US manufacturer tried to launch its videophone to the public. But attempts to popularise video calling throughout the twentieth century were uniformly disastrous. Until digitisation, manufacturers could never find a way to make videotelephony cost-efficient enough for a mass public.

…in episode of F.R.I.E.N.D.S could squeeze two minutes of novelty and gags out of the mere presence of a videophone…

Because it never caught on, the video call remained a futuristic idea right up to the point it became normal. Even in 1997, only six years before the Beta version of Skype was first released to the public, an episode of F.R.I.E.N.D.S could squeeze two minutes of novelty and gags out of the mere presence of a videophone. Monica’s millionaire boyfriend Pete has a videophone installed in his home; it is a sign of his immense wealth as well as an object of comedy. Pete calls his own apartment and the cast hide from view but are discovered. Then, after the call, Monica accidentally uses the phone’s voice command to call Pete’s mother. This was just twenty years ago, yet the everyday travails of the Zoom age provided a source of giddy excitement and laughs.

In the same year, the novelist David Foster Wallace’s, Infinite Jest imagined the history of videotelephony from a future where it’s been and gone. Users, tired of confronting their own bloated and poorly-lit faces, are offered something like a Snapchat filter: a ‘broadcast-able composite of a face wearing an earnest, slightly over-intense expression of complete attention’. This proto filter is then supplanted by the less expensive option a polybutylene-resin mask of the user’s face which can be slipped on before making a call.

Zoom may have added a skin-smoothing filter to their service, but thankfully, on wearable masks, Wallace was wrong.

Our last stop in the historical tour of videotelephony is Beyoncé’s 2009 single, ‘Video Phone’ and its accompanying video, in which a man with a camcorder for a head dances around while Beyoncé sings ‘If you want me, you can watch me on your videophone’. Despite being the most recent, perhaps even the last, image of the videophone-as-future, this video somehow looks the oldest, especially when you consider that Apple released FaceTime only a year after Beyoncé’s single was released. Who could have known that the word ‘videophone’ and the image of the camcorder would disappear so completely from our lexicon and seem so old-fashioned?

There is something eerie about watching all of these images of the video call as it was anticipated in the past. It reminds us how quickly our world can change, how quickly the new becomes normal, and how quickly the future becomes the past. As the novelist Ben Lerner wrote, nothing looks older than what was futuristic in the past.