Horrorscope: What the recent discoveries in the Zodiac case really reveal

California’s infamous Zodiac Killer of the 1960s has made headlines again, after a fifty-year-old cipher was cracked. What does this new evidence actually tell us about the case? Mae Losasso investigates.

I’m looking at the letters ‘ebeorietemethhpiti’ and wondering how I can twist them into sense. Is this an anagram? I’ve got ‘epithet’, ‘epitome’, ’emptier’, and ‘tiptoe’, as well as the names Hettie, Timothee, and Bert.

Scrap that. Forget the anagram. Maybe the letters are substitutes for numbers. Or could it be an acrostic? Or the so-called Caesar Cipher, with each letter of the alphabet shunted back three places? I could lose hours on this high-stakes puzzle. Because if I cracked it I’d achieve more than the requisite puzzle-completion smugness; I’d have solved one of the twentieth century’s most elusive criminal investigations.

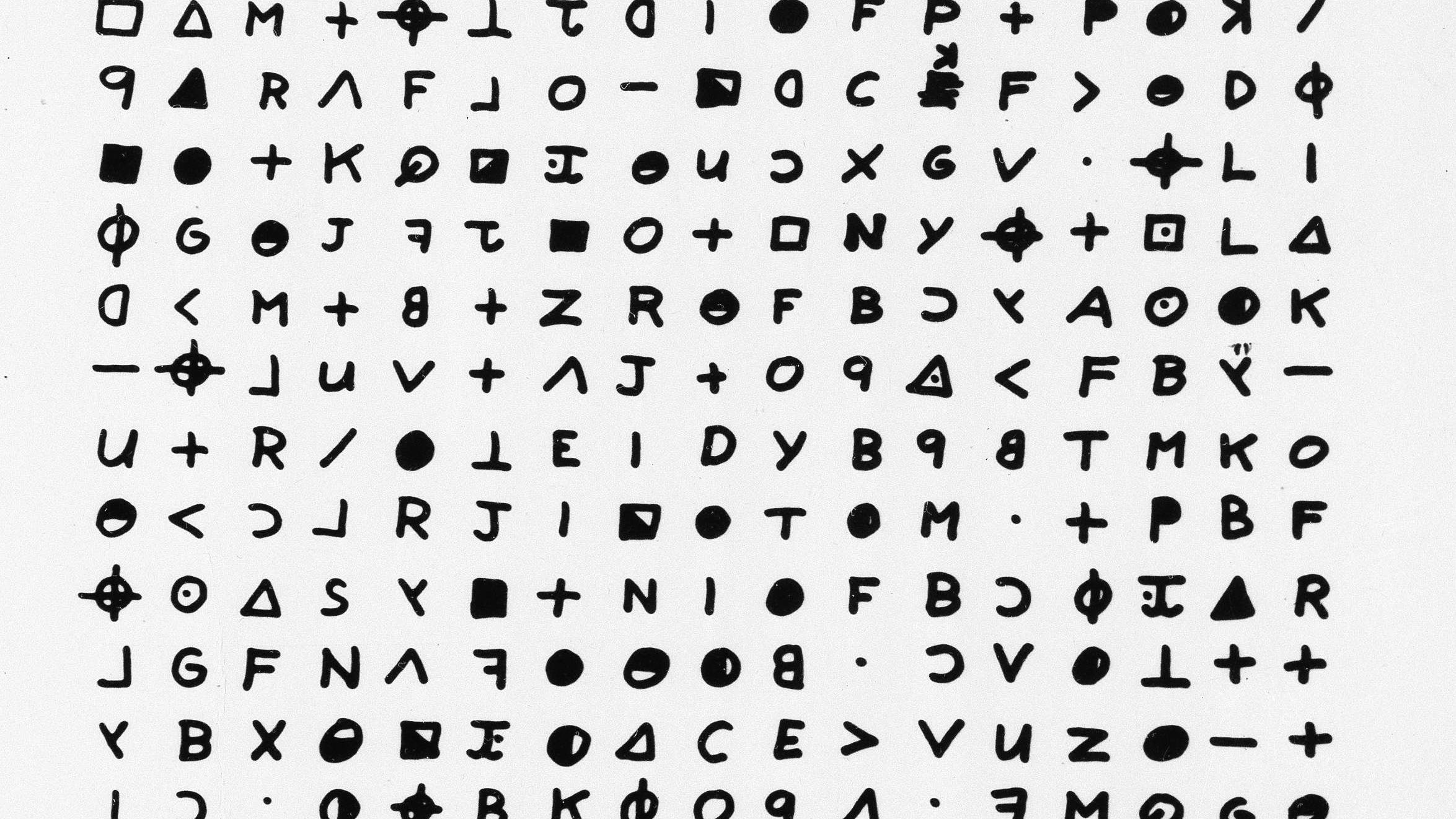

The string of jumbled letters that I’m agonising over were included in the first of four ciphers mailed to newspapers in the San Francisco Bay area in the late 1960s. For anyone unfamiliar with the case, these letters were sent by the so-called Zodiac Killer, a serial murderer responsible for the deaths of five known victims – though Zodiac himself claimed to have murdered thirty-seven in total. Who was the Zodiac? The answer, to this day, is a mystery, and the case remains open in the Northern Californian cities of San Francisco and Vallejo, as well as Napa and Solano Counties.

Zodiac (2007)

Perhaps you’ve heard of the book, Zodiac, published by cartoonist-turned-amateur-detective Robert Graysmith in 1986. Or else, you’ve seen David Fincher’s 2007 film of that name, dubbed the 12th greatest film of the twenty-first century in a 2016 BBC poll.

Or maybe the name Zodiac Killer is ringing a bell because you read about the case in the news last week. After fifty-one years, cipher number four – dubbed ‘Z-340’ – has been cracked by software engineer David Oranchak and an international team of private citizens who have been working on the Zodiac ciphers for years.

But let’s go back, all the way, to August 1969, when the Zodiac made headlines – quite literally – by sending his letters and cryptograms to the press and demanding that they be published. On August 2nd, 1969, the San Francisco Chronicle ran their segment of the cipher (he distributed the code across three different papers) on page four. Six days later, school teachers Donald and Bettye Harden had cracked the code.

“I like killing people because it is so much fun,” reads the first line of the Chronicle cipher. “It is more fun than killing wild game in the forrest because man is the most dangeroue anamal of all to kill something gives me the most thrilling experence [sic].”

The recently cracked cipher Z-340 was mailed to the Chronicle in November of that year, but remained unsolved until earlier this month. Sadly, deciphering the code hasn’t helped pin down a prime suspect, but it does reveal something that lies at the heart of the Zodiac killings, and in the culture that has sprung up around it in the years since: a perverse association with fun.

Array“I hope you are having lots of fun in trying to catch me,” writes the Zodiac, in Z-340. The rest of the cryptogram is followed by ramblings about gas chambers, slaves, and the death of “paradice [sic].” All of Zodiac’s letters and ciphers manage, like this one, to be both sinister and facile, even banal – but perhaps this is where the horror resides. Because, from day one, Zodiac was turning his killings into a game; an object, as the deciphered codes confirm, of fun.

And the newspapers that published Zodiacs letters and cryptograms were complicit: they transformed the tragic murders of young couples into mind-bending puzzles and epistolary fictions, like the nineteenth-century fashion for serialising stories in weeklies. In doing so, they opened the case up to the public. Any Tom, Dick or Harry (or Paul, Robert or David, as it turned out to be) could follow the clues in the papers and start building their own case – and that’s precisely what they did.

After Donald and Bettye Harden’s Saturday-morning, code-cracking-over-breakfast sesh (neatly captured in Fincher’s dramatisation), Chronicle journalist Paul Avery (played by Robert Downey Jr in the film), took up the mantle of cracking the case, vigilante style.

Receiving a tip off from an anonymous source, Avery found circumstantial evidence that linked the Zodiac killings with an unsolved murder from 1966. Much to the chagrin of leading investigator, Dave Toschi (played to perfection by Mark Ruffalo in Fincher’s film), Avery bypassed the police, making his story public – and adding his little piece to the curious Zodiac puzzle.

David Toschi, Detective who pursued the Zodiac Killer

Then there was Robert Graysmith, the cartoonist who had been working alongside Avery at the Chronicle in 1969. Having followed the case from the start, boy-scout-in-a-man’s-body Graysmith quietly and meticulously amassed tidbits over the years. By the mid 70s, when the case was all but closed, Graysmith reignited police interest, gaining access to case files, getting Toschi back on board, and digging up fragments of evidence that had previously been overlooked. In a documentary released around the making of Fincher’s film, Graysmith explains that he wanted to make “a book that served as a political cartoon. And if I couldn’t find it, then all the information was there and so […] the public would catch this guy. They would have all the pieces.”

And so, with the publication of Zodiac, Graysmith handed the case back over to the public in 1986, with more pieces and more puzzles – and more fun to be had. As Jake Gyllenhaal, who plays Graysmith in the film, muses, “I think that Robert found it actually fun. I think that’s hard for people to understand – that this man enjoyed searching for this person, whereas a cop would have done it because it was his job.”

For one scene, Fincher had trees uprooted and helicoptered into the exact spot where other trees would have stood in 1969

Graysmith’s book provided the impetus for the 2007 film (that medium of entertainment, recreation, fun). Director David Fincher was, by all accounts, methodical and uncompromising (some scenes required up to 70 takes) and this extended to his research. Case files were made available to the production team, while detectives, journalists, and even victims were contacted in the interests of filmic fidelity. For one scene, Fincher had trees uprooted and helicoptered into the exact spot where other trees would have stood in 1969. Gyllenhaal even used Graysmith’s drawing board and pens as props. Like Graysmith, the film’s protagonist, Fincher found himself morphing from director to detective and Zodiac the film became yet another part of the fact-based fiction, “another step towards solving the case,” as Mark Ruffalo observed.

ArrayCop dramas, whodunnits, and murder mysteries are time-honoured literary genres, and they lend themselves particularly well to cinema. But there’s something especially compelling about the unsolved true crime story. It leaves every viewer wondering if they might crack the case, turning all of us into would-be homicide detectives. It’s the very reason why Oranchak and his buddies set up their own private code-cracking enterprise.

Watching the film again, in light of the newly cracked code, it’s striking how intertwined fact and fiction are – and continue to be – in this unsolved case. In Zodiac’s last known letter, mailed to the Chronicle in 1978, the killer writes, “I am waiting for a good movie about me,” a line that Fincher includes in the film with meta self-consciousness. And as I watch, I’m wondering if Zodiac ever saw this film, this movie he had been waiting for. Because, in this tumble of fact and fiction, everything gets jumbled up, like that string of letters at the end of that first cipher from 1969.

in light of the newly cracked code, it’s striking how intertwined fact and fiction are

As readers, as viewers, we’ve read and watched and dramatised and laboured over the case. At every step, we’re playing the game the Zodiac set for us, we keep coming back to that blood-soaked Rubik’s Cube, twisting and turning until some new piece of the puzzle falls into place.

And yes, as it turns out (and dark as it is to admit it), we have been having fun with it. Reading cipher Z-340 all these years after it was written, perhaps that’s the most chilling thing: that, more than fifty years later, we’re still pushing the pieces of the puzzle around. An admirable instinct or a ghoulish fascination? Well, that’s up to you – I’ve got an anagram to solve.