The Olympic Studios was going to be converted into a supermarket and block of flats before a hero swept in with a bold restoration proposal – we spoke to owner and founder, Lisa Burdge about this amazing journey.

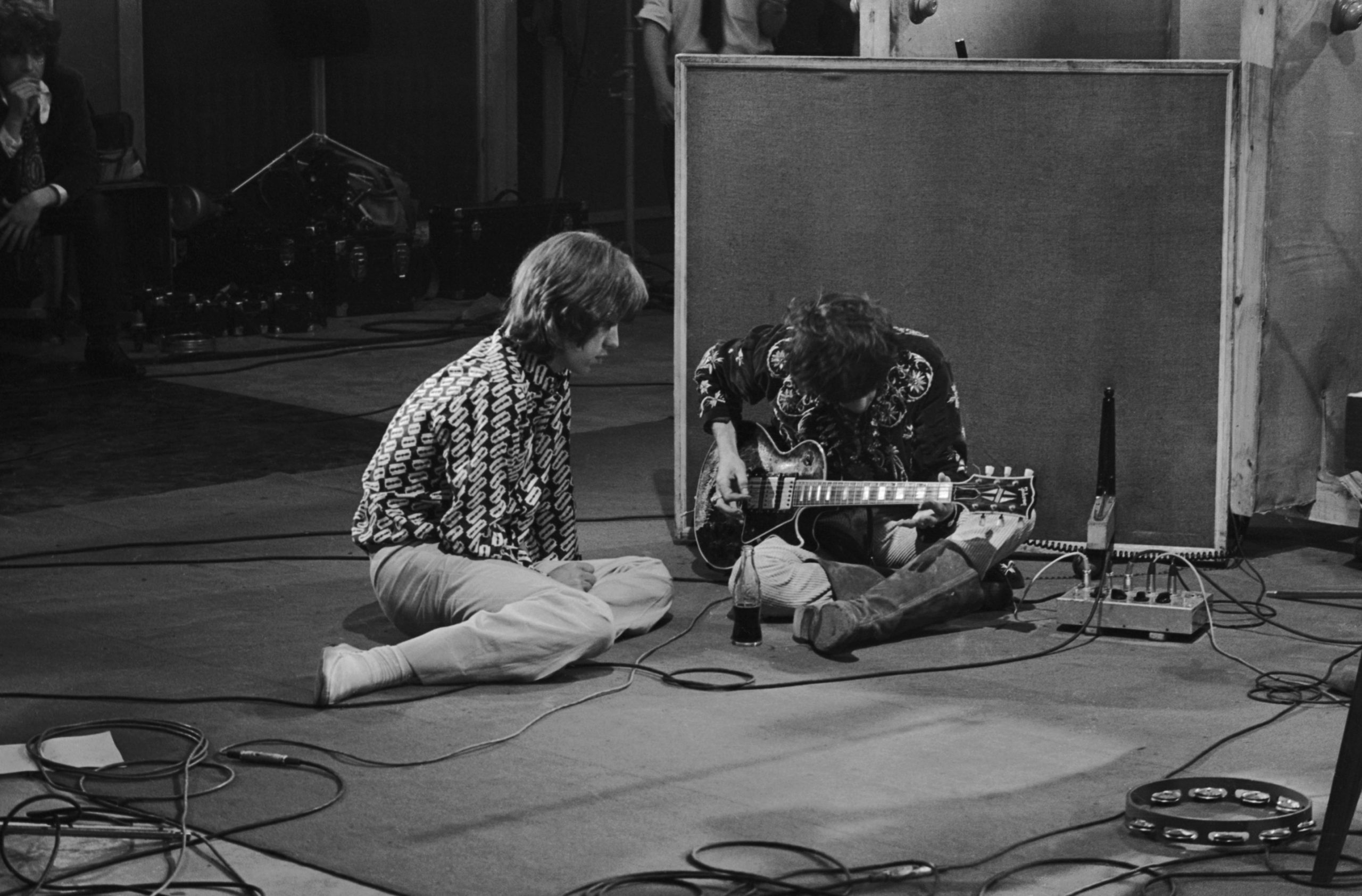

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards during an all-night Rolling Stones recording session at the Olympic Studios in Barnes, southwest London, 7th July 1967. (Photo by Terry Disney/Daily Express/Getty Images)

Olympic’s music legacy began in 1966 when it was converted from a cinema to the Olympic Sound Studios, with enough room to house a 70-piece orchestra. The Rolling Stones were among the first clients, recording six consecutive albums between 1966 and 1972, whilst The Beatles worked here to record the original tracks of ‘All You Need Is Love’ and ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man’. The Who recorded two of their albums at Olympic and it was where Led Zeppelin recorded their debut record in October 1968, before David Bowie recorded the innovative Diamond Dogs LP. But the Olympic wasn’t just a place for musicians to record, the studio was also important for film, with the soundtracks to The Italian Job, Jesus Christ Superstar and The Rocky Horror Picture Show all developed in the Southwest London building.

It’s now seen a revival, acting as an institution that gives back to the community as a cinema, members club, music room and recording studio. And, most importantly, the rescuing of the entire building for the arts was decided during a drunken session…

Jimi Hendrix recording at the Olympic in 1967

Rolling Stones members Mick Jagger and Keith Richards at the Olympic Sound Studios while making Jean Luc Godard’s semi documentary movie ‘Sympathy for the Devil’, aka ‘One Plus One’, 12th June 1968. (Photo by Larry Ellis/Express/Getty Images)

How did this venture begin?

My husband and I were with friends in the curry house opposite and we were very drunk. We saw the Olympic for sale across the road. We said, ‘What’s it going to be?’ before a friend of ours walked in and said, ‘Flats and a supermarket’. We were horrified and so vowed in our drunken state that we were going to save it.

The next morning my husband got very excited. All our friends sobered up and bailed out in the plan to save it but he was like a dog with a bone saying, ‘We have to do this!’ The agents wouldn’t even let us see it but because we live locally, we befriended the security guard called Eddy. He snuck us in and our jaws dropped to the floor. The history was amazing!

I was absolutely f*cking terrified. It was scary as hell. We sold everything, shoved our pensions in, and were left with nothing.

What sacrifices did you make to fulfil this drunken promise?

We had to sell our house. We were just tenacious and wanted to actually make it happen. I was absolutely f*cking terrified. It was scary as hell. We sold everything, shoved our pensions in, and were left with nothing. It was all a bit of ‘shit! bollocks!’ scramble (for want of a better phrase!), but, finally, we bought the place.

How did you start on its conversion into a cinema and arts community centre?

The Olympic began as Byfeld Hall, opening its doors in 1906. It was built as an entertainment centre for the local community and was a ‘bioscope’, an early form of cinema. Early audiences were treated to footage of King Edward VII’s funeral and the hall was used for a variety of entertainment activities. Some of our film friends suggested turning it into a cinema once again, and so we did. We ended up renting the house next door that was actually owned by Keith Flint, the lead singer of the Prodigy.

When did it all sink in, the scale of what you’d committed to and how you eventually pieced it all together?

I remember a really amazing day when we drilled through ten feet of cladding that was covering every single window, and the light came in. It was just a wonderful feeling. We did an open day for the local community – because they hadn’t been inside in years! – with more than 2000 people streaming through the doors. A guy said to me, ‘Oh my God it’s like I’m Charlie from

A guy said to me, ‘Oh my God it’s like I’m Charlie from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory! I’ve got the golden ticket!’

It’s a beautiful venue, talk me through the design of the new building.

I love anything design-oriented and discovered this place in Devon, an architectural salvage place where people go and strip out cruise ships. It’s an incredible graveyard of 60s and 70s vessels. A lot of our furniture comes from that. There’s also an incredible chandelier in the member’s club with 125 light bulbs that we strung up ourselves. Me, my husband, and our eight-year-old son were on a scaffold hanging every single ring, it took days. We couldn’t move afterwards, we were so knackered. There’s a couple of beautiful paintings on the walls here by Ronnie Wood that go over the holes left by the speakers. Every object has a story.

What’s so special about the acoustic engineering here at the Olympic?

Sound’s been essentially ignored by a lot of cinemas. Dolby had just brought out this incredible system called Dolby Atmos – 3D sound. We installed it, the first London cinema to do so. It was just spine-tingling!

We showed Gravity, the Alfonso Cuarón movie and you could hear the spacecraft moving around and over your head. The sound engineer from the film came in himself and said, ‘This is what I wanted this film to sound like’.

Then Jimmy Page from Led Zeppelin came in to launch the remastered version of Physical Graffiti, which was originally recorded here. He stood on the stage afterwards and said, ‘You’ll never hear this album as good as it sounds in this room’. Just hearing that just made it all worthwhile.

The cinema’s impressive plush interior today

Why do you think these artists chose the Olympic?

You came over the bridge and there was no tube station. There was a feeling that you were coming to the countryside and you could relax and just chill out. It was private. Allegedly, John Lennon used to come in his psychedelic Rolls Royce. He had a driver who used to drive underneath the building and would have a boot full of Crystal champagne. Oasis used to record here, as did the Arctic Monkeys, and there was a feeling that because you were out of Central London, you could let your guard down and people didn’t really bother you. I think that people in the village were very used to seeing people in and around the space.

The new floor will be a haven for new music, what are your plans for it?

This place was built for the community and we’ve kept that ethos. We’re creating a recording studio that’s going to have an altruistic element to it, a philanthropic element even. People can invest in it, but they are not just investing in the studios, they’re investing in new recording talent. It’s a fantastic wheel of sponsorship and gives people the opportunity to promote young up-and-coming bands. Eric Clapton’s donated a guitar for us to auction and we’ve received a donation of the most amazing mixing desk that’s apparently the dog’s bollocks of mixing desks. As cheesy as it sounds, it means we’re giving something back.

Do you ever get a chance to sit back and look at what you’ve created?

Not really! You have so much to get on with that you just put one foot in front of the other and every day, every month, every year, it brings new challenges. You don’t really notice what’s going on, it’s so fast. But I do actually get quite emotional. It’s just such a privilege to be able to have been involved in this. I feel like a custodian saving a stately home. I’m looking after it before passing it on.