Slasher films are stereotyped as bloodsoaked B-movie schlock. However, from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre through to Bodies Bodies Bodies, the subgenre has long been hacking away at horror cliches.

We all know what the stereotypical slasher film looks like. Some masked and voiceless serial killer keeps hacking away at horny teenagers for an hour and a half before the virtuous virgin girl does away with him except not really because Hollywood needs sequels. The end. It’s the vision that non-horror hounds have long maintained thanks to the endless deluge of Halloweens and Friday the 13ths in the 1980s.

However, the stereotypes held against the slasher subgenre are sometimes completely unwarranted. At its best, it’s a style of filmmaking that’s torn the horror rulebook to pieces more violently than anything else. It has pushed scary films forward in terms of what they can get away with, then veered back to unpick its own tropes and spawn a new generation of masterpieces. No filmmaking niche so small has had such an eventful evolution and self-reassessment over its lifespan.

Even at its very outset, the slasher film was plumbing new depths of depravity. Films about masked killers tormenting a large number of victims have been getting made since the likes of The Bat in the 1920s, yet it’s 1974’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre that’s generally regarded as the first bona-fide slasher. Despite having a far lower body count than the films it’d inspire (a mere five people), so many of the future hallmarks are here: Leatherface is a cannibal whose face is concealed by other humans’ skin, and he runs around with a chainsaw murdering people until one final girl in the back of a pickup truck.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Credit: Bryanston Distributing Company

Despite being made for a mere $140,000, Texas Chain Saw stunned America. Not only was Leatherface inspired by the antics of Ted Bundy, but it took the documentary aesthetic that had, the previous year, made The Exorcist the scariest film of all time and cranked it to 11. This was an instance of a shoestring budget working in a film’s favour, with the grainy quality, hideous locations and absence of a blockbuster soundtrack eliminating all Hollywood pretence and making things feel… real. The very real-life location of middle-of-nowhere Texas certainly didn’t help filmgoers sleep at night.

The following Christmas, Black Christmas took things even further. It felt realer and even more chilling. The killer in future Christmas Story director Bob Clark’s slasher was completely faceless and masked by darkness, inspired by the classic “the call was coming from inside the house” urban myth. It was also a sinister subversion of the holiday season, with all the action taking place inside the home. At Christmas, the house is (ideally) a happy place: warm and full of family and friends. Well, now not even that can make you feel safe, thanks to this film shitting you up with its jumpscares and suspense.

Following those formative films, John Carpenter’s 1979 classic, Halloween perfected the formula, with a silent, masked and quasi-supernatural killer piling up teenage bodies for seemingly no reason (the less said about the sequels’ attempts to explain that reason, the better). Then, in 1980, Sean S. Cunningham’s Friday the 13th became the ultimate cash-in, borrowing all of the tactics that made Halloween a hit so that it could go on to gross 100 times its modest budget. It did make one key addition, though – it closed with one last, shocking jump scare, directly inspired by the dream that closed Carrie. Consider another slasher trope established.

Friday the 13th. Credit: Warner Bros.

Of the post-Halloween slasher boom, though, the smartest entry was A Nightmare on Elm Street. By its 1984 release, Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees were basically supernatural entities in their own right – how else could they keep coming back and generating more money? – so director Wes Craven went all-out with a fully impossible killer.

After Texas Chain Saw made real-life rural America terrifying and Black Christmas put serial killers in the home during the holidays, Freddy Krueger decided you can’t even feel safe in your sleep. It was a concept that gave the slasher genre even more unpredictable kills – perfect timing considering, as far as the mainstream was concerned, the genre was beginning to run out of tricks.

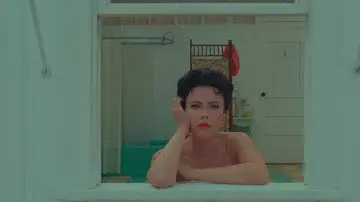

Scream. Credit: Dimension Films

Clearly, one slasher masterpiece wouldn’t cut it for Craven, though. In 1996, he and writer Kevin Williamson (who’d later affirm the slasher comeback with I Know What You Did Last Summer) created Scream: a meta-horror with a new wrinkle, where the characters were all well-versed in genre cliches. Scream proved to be a massive hit, thanks to its smart writing, as well as it arriving almost twenty years after the slasher craze started. Nostalgia famously runs in a twenty-year cycle – which was a lesson some slasher filmmakers clearly didn’t learn when they tried to revive the genre again just ten years later.

The big-budget slashers of the late-2000s and early 2010s, like the Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street remakes, were destroyed by critics and audiences alike. So, the era’s attempt to resurrect the genre is widely viewed as a dud – but it was actually the box office bombs that outsmarted the dumbed-down remakes dominating cinema screens.

Underrated to this day is Tucker and Dale vs Evil, the directorial debut by Eli Craig (who also made the overlooked Omen parody Little Evil in 2017) reverses the classic “hillbillies killing teenagers” plot in ingenious ways, and also carries wholesome messages about not judging books by covers. To say anything beyond that is to spoil a masterpiece.

Similarly subversive was The Cabin in the Woods. Despite being masterminded by alleged prick Joss Whedon, it pulls the “teenagers in a haunted cabin” premise into unprecedented territory. Slashers get a send-up in the masterclass horror-comedy – as does every other subgenre of horror along the way. However, again, to reveal any more is to spoil the fun.

Cabin In The Woods. Credit: Lionsgate

Slashers quickly returned to dormancy in the early-to-mid-2010s, but then we got the legacy sequel to Halloween in 2018. Although the films in that new trilogy ranged from OK to inhumanly bad, their success opened the door for much smarter slashers. Ti West’s X added ruminations on ageing and fading stardom into its kill count in 2022, while the same year’s Bodies Bodies Bodies played with the “mystery killer” format to build to one hell of a punchline. Scream returned last year with even more meta-commentary, this time satirising the concept of “requels” (films that continue a series’ story while also being accessible to new audiences) while itself being one. Scream VI will directly pick up where that left off this month, and doubtlessly will carry the same wit with it.

As a result of all these evolutionary and self-aware masterpieces over the course of almost fifty years, it’s safe to say no horror genre has had the journey that the slasher has. It’s widely derided as a style more obsessed with a body count than a nuanced script, but that simply isn’t true.

Scream VI is in cinemas now.