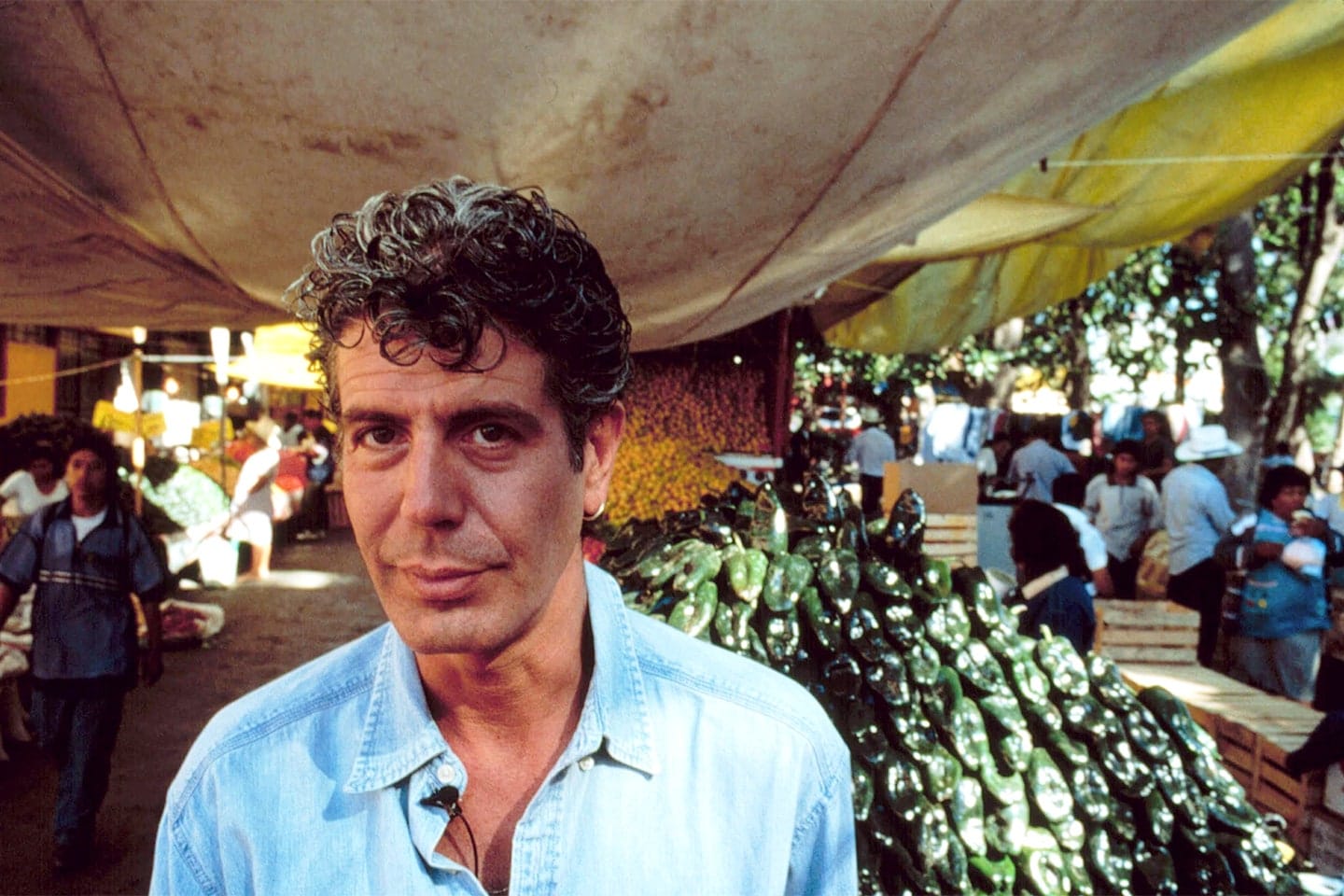

Legendary food critic AA Gill described Anthony Bourdain’s seminal Kitchen Confidential and its author as ‘Elizabeth David meets Quentin Tarantino’. Sam Moore looks at how this couldn’t fit the late chef, traveller and writer any better.

Elizabeth David, like Bourdain (Tony to his friends) had a voracious appetite for food and the role it played in people’s lives and in the post-war years was the most influential voice on the British culinary scene. She was also a perpetual rebel, shunning her upper class upbringing to abscond with a married Communist in Greece – an act subversive act that would make Tony smile.

The Tarantino comparison he’d be less keen on, after publicly accusing him of being “complicit” in Harvey Weinstein’s many heinous crimes but there is a similarity between these two iconoclasts.

Ethiopia

They both have a punkish spirit to be deliberately provocative and approach the written word with a luscious and loquacious flair developing a voice that is uniquely theirs, never to be confused with somebody else.

And like Tarantino, Bourdain had a limitless enthusiasm for the world around him, gorging in the planet’s food, culture and history until he was full, and then some.

It’s hard to imagine Bourdain dealing with the lockdown life of the last 16 months, stuck in one place with nowhere to travel to, no restaurant open to eat in, no strangers to become friends with. His much-loved shows No Reservations and its spiritual sequel Parts Unknown took him as far away as the Congo and Cambodia and to the cooking Mecca of Noma in Copenhagen or a chip shop in Glasgow.

Along the way he met a hero in Iggy Pop and ate oxtail with Omar from The Wire, he went bowling with the luminaries of the Nashville music scene and traipsed to Madagascar with film director (and vegetarian) Darren Aronofsky, or ate cheap noodles and a ice cold Hanoi beer with Obama in Vietnam.

Anthony Bourdain was a man never settled, always in search of something, anything and the more obscure or cult the better. He had a novelist’s curiosity and a humanitarian’s heart, always finding threads that tie people together, he had a spirit that unified, that sat and listened and told stories sensitively. The story of his work was that whilst parts of the world are vastly different, the human beings that occupy it are very similar.

As the world tentatively starts to open up again and flight routes become available and restaurants welcome the public back to tables, it’s never been more obvious how much the ethos of Anthony Bourdain is needed.

The freedom of travel, the joy of experience, the thrill of discovery – it has all been put on a global pause for over a year disconnecting humanity from itself, reducing communication to online conversations and small talk with delivery drivers.

Lived curiosity has had to take a back seat to the greater good of public health with misinformation and division wreaking havoc across social media, the antithesis to Bourdain’s endless search for truth.

His programmes, as well as providing intimate insights into culture and food offered details on history left outside of the curriculum.

Most striking is his masterful episode on the Congo which begins with a breakdown of the country’s tragic and tumultuous history, from the brutal reign of King Leopold who claimed the land of his own to the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the nation’s first democratically elected leader to the still ongoing civil war that has seen the DRC divided up by various militias. Throughout the episode, the viewer learns of the Congo’s mass of natural resources that have been exploited by the global north, the roles foreign powers like Britain, Belgium and America have played in undermining economic progress and how the beer factories never stop rolling in a country with a perilous supply of electricity.

You see the realness behind the headlines, the unreported stories ignored. He didn’t feed his audience soundbites, he respected them too much for the bland platitudes that swamp so many travelogues, he wanted to learn and he wanted his watchers to learn from him.

If you wanted an alternative and honest view of the world you’d go to Bourdain. His episode in Cuba, a country in most of Western media that is ubiquitously portrayed as backwards with tyrannical leaders and food shortages even though it is estimated that 1.5 million people are forced to go a day without food in the UK.

Bourdain found the beauty and revolution in Cuba, its obsession with boxing, deep heritage in rum and cigars and remarkable cuisine that includes everything from pig’s head soup to sushi fresh off the boat. He told stories of the island many wouldn’t have known, associating the country with Cold War images of Fidel Castro and murals of Che Guevara.

The episode, as much as any, emphasised the importance of travel and experience, of finding out for yourself the stories of people and the planet, to enter the unknown and embrace all that holds.

Re-watching the hundreds of episodes readily available on Netflix and Prime Video over lockdown serves as a blunt reminder of just what a loss Bourdain is to the world. His honesty, not just in his views on food and culture and politics but also about his personal life.

He wore the scars of drug addiction candidly and his depression was no secret, there was nothing fake about him. Bourdain fiercely advocated for the things he believed in especially so-called peasant foods such as the nose-to-tail style of cooking made famous at Fergus Henderson’s unparalleled St John. He was as happy with a burrito off a street cart in Juarez as he was being served up nine different courses with accompanying wines in a Michelin starred Parisian paradise.

Oman

It was what made him feel like one of us, an ordinary bloke who could pass as your favourite uncle who had a knack for great Christmas presents – he just so happened to be paid to go around the world living out his dreams, something he never stopped being humble or grateful about.

Restaurants are again open, cultural sites can be visited and you can fall upon a stranger and talk to them about Dario Argento movies for five hours whilst getting increasingly drunk without the fear of arrest – all things that would have made Anthony Bourdain grin with glee because they are the unifying events of humanity.

You can bond with anybody over good pizza and whisky, find a friend for life over a glass of sake and the best hours of your life are often spent in glorious company with glorious food and a cold beer.

This is what his films told his millions of fans around the world – a message so simple can be forgotten in the noise and pace of modern life where work is precarious and money scarce. He celebrated the simple things, the things that are simultaneously a privilege and pleasure, the things taken for granted and the things treasured.

Brazil

After a year and a half of social distancing, lockdowns and enforced closures, Anthony Bourdain’s message has never been more prevalent. The world is weird, it is divided and it is angry, only a fool would think otherwise and whilst Anthony Bourdain’s body may no longer be with us, he spirit is and needs to be.

Above all, he was a truth teller, furiously honest and beneath the New Yorker swagger was an introspective existentialism, always questioning, always searching. From the hedonistic nineties where he was one of many in the dysfunctional menagerie of a kitchen he matured to being a powerful advocate for social justice, unafraid to call out friends such as Mario Batali for their allegedly predatory actions.

His actions in the later years of his life revealed a mighty moral integrity and he is an example for listening and learning from others, of always being empathetic – his life, his work emphasised humanity’s collective togetherness.

Wandering curiosity in search of new marvels far and wide is a fundamental part of life on Earth, it has driven discovery and invention, mixed cultures and created new and these things have been an impossibility throughout the pandemic.

Hopefully, like him, we can be eating ham in Bologna or watching a wrestling match in Istanbul again soon.