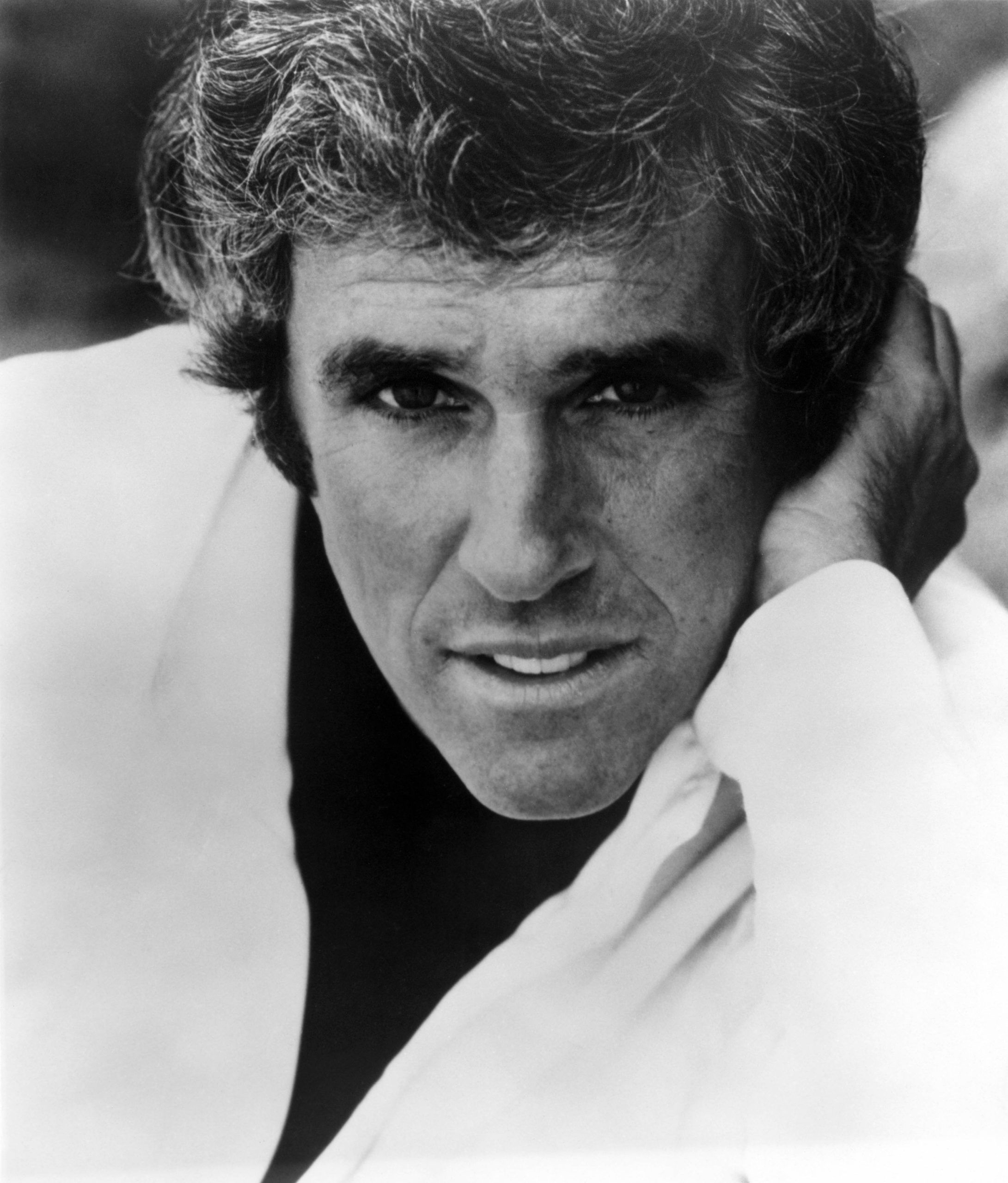

His career always involved strange combinations – part behind-the-scenes hitmaker, providing songs that made stars, and an on-off star himself. Onstage or off, however, his songs embody the spirit of a musical current that has always been there, and always has a place: sophisticated showmanship.

Bacharach’s music, like much of the best in straightforward classical composition, made sophistication seem natural. His combination of unusual chord, key and time signature changes and sinuous melodies imbued a melancholic, pained truth to love songs. But as Bacharach himself said in a 1964 BBC interview, he “broke many, many rules, musically – and not intentionally. It just came out that way.”

Born Burt Freeman Bacharach in Kansas City, Missouri in 1928, to Jewish parents – Bert Bacharach, a newspaper columnist, and Irma Freeman, an artist/songwriter – he was immersed in divergent musical streams from an early age. Studying classical cello and piano as a child, he furtively frequented jazz clubs as a teenager, seeing Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonius Monk, Charlie Parker, and Count Basie.

Studying music in Montreal, New York, and California, he took jazz harmony, alongside classical composition with modernist giants like Henry Cowell, Bohuslav Martinů, Darius Milhaud – who told him never to be ashamed of coming up with a memorable, whistle-able tune.

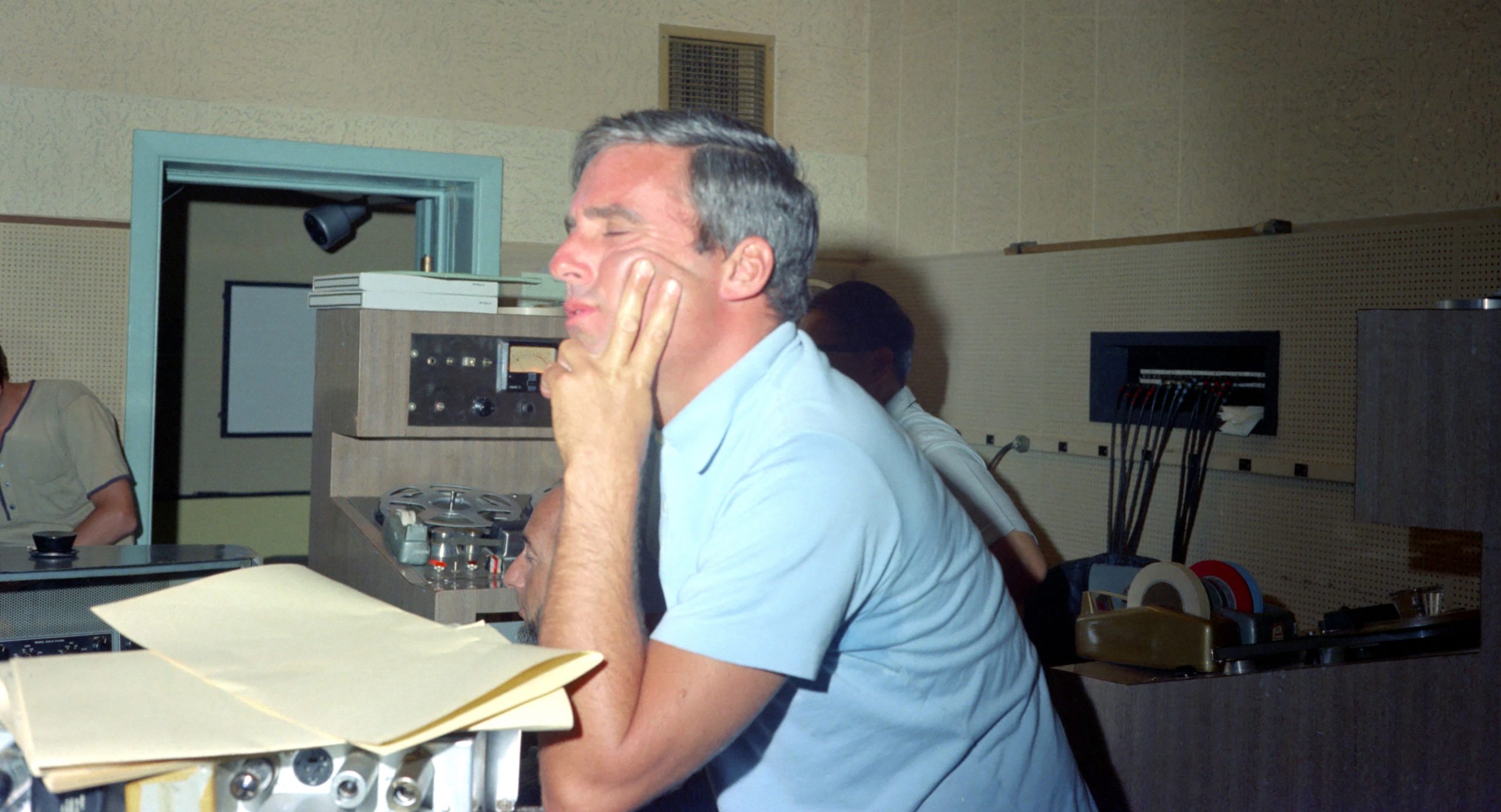

Returning to New York in the mid-50s after army service in Korea, he fell into gigging with showmen like Vic Damone and the Ames Brothers as a piano accompanist and arranging and conducting for Marlene Dietrich’s European cabaret tours. Bacharach’s experience, gifts and understanding of music were diverse, allowing him to exploit the subtleties of an orchestra (the famous ‘Bacharach trumpets’, for instance) or add further depths and shade to his preternaturally ear-worming melodies. Bacharach arranged, conducted, and produced his work himself. Producer Phil Ramone called him “one of the most amazing musicians in the world”.

Things really kicked off for Bacharach on meeting lyricist Hal David in the mid-50s, right around the corner from New York’s fabled Tin Pan Alley, the home of the Great American Songbook tradition. Standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Rodgers-Hammerstein or John-Taupin, it became a song-writing partnership for the ages. Their hits came fast, beginning with ‘The Story of My Life’ for Marty Robbins in 1957 and ‘Magic Moments’ for ‘Perry Como’ (UK No.1) in 1958.

David, seven years Bacharach’s senior, had already been writing through the 40s for the bandleaders like Sammy Kaye and Guy Lombardo and singers from Frank Sinatra to Sarah Vaughan. As with most great partnerships, the two’s inclinations made for complimentary contrasts. Bacharach’s sweet melodies made delightful foil to David’s smart, funny, specific lines. Take this classic sentiment from 1968’s ‘I’ll Never Fall in Love Again’, for instance: “What do you get when you kiss a girl? / You get enough germs to catch pneumonia / After you do, she’ll never phone you.”

Dionne Warwick, Stevie Wonder, Elizabeth Taylor, Gladys Knight, Burt Bacharach and Carole Bayer Sager at a performance of the song ‘That’s What Friends Are For’ on the television show ‘Solid Gold’ in Los Angeles, USA, 1986. On the left is Clive Davis, President of Arista Records. Photo: Vinnie Zuffante/Michael Ochs Archives.

Bacharach’s music, meanwhile, was always made distinct and, although doomed to be labelled with a tarred brush-off as ‘easy listening’, was forever adaptable by his equal gift for melody with unexpected changes in harmony and rhythm. No less a music nerd than Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen called his style a combination of Ravel and street soul.

Bacharach’s innate musical adventurousness constantly found him seeking to branch out. He started writing for pop crooners but moved into rock with the arrival of British Invasion, working with the likes of Manfred Mann, for whom he wrote ‘My Little Red Book’, a proto-jazz-rock number released in 1965 and filled with weird modulations and orchestra-imitating organ riffs – showing that Bacharach was equally unwilling to adapt his style to basic rock n’ roll forms.

Then, take the version recorded a year later by the trailblazing California band Love, in 1966. It’s a completely different song: imbued by a garage and proto-punk sensibility, with the raw and ragged vocals of frontman Arthur Lee, the complexities of the song are smoothed out, transformed in a driving, tambourine-laced backbeat. And yet the song works even better – Bacharach’s musical ideas are placed in the service of something grittier. It made for a sound that looked ahead to music made a decade later.

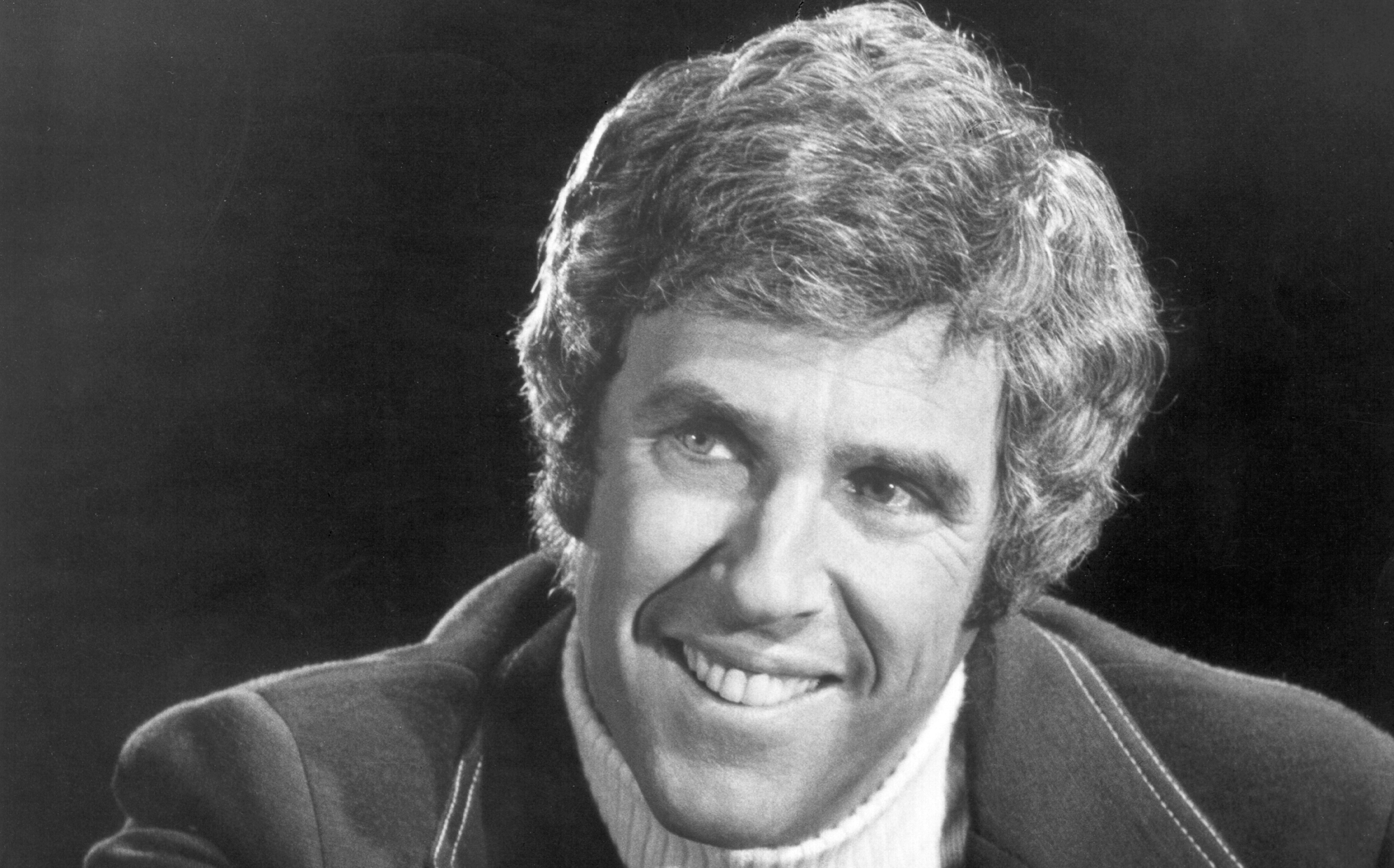

This adaptability may be the core of Bacharach’s genius. Like ABBA, there’s something deep in the DNA of much of his material that simply works and can be bent into new shapes without losing its direct, instant appeal. Crooners, soul singers, jazz artists, rock bands all took and reworked his material, and a whole new generation of musicians would later be thrilled to work with him. At the Royal Albert Hall height of late 90s stardom, Noel Gallagher would coo out a version of ‘This Guy’s in Love with You’, Bacharach accompanying on piano.

Bacharach and David’s banner decade was undoubtedly the 60s, in which they turned out hit after hit with effortlessness and invention. Beginning in 1962, they enjoyed a fabled collaboration with soul singer Dionne Warwick – their most famous hit being ‘Walk On By’, in 1964 – which proved fruitful over a decade, as well as others with Aretha Franklin (‘I Say a Little Prayer’), Cilla Black (‘Anyone Who Had a Heart’) and Dusty Springfield.

A cover of ‘Baby It’s You’, hollered by John Lennon, graced the Beatles’ debut LP. They wrote for the movies, producing the Oscar-winning ‘Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head’ for the classic 1969 Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and the theme for ‘What’s New Pussycat?’, belted with true gusto by Tom Jones. All in all, the pair had written over 100 songs together by the end of the decade.

In the early 70s the partnership would unravel, following a commercial flop on their musical version of ‘Lost Horizon’, which led to lawsuits and acrimony over royalties. Bacharach’s second marriage also fell apart, and he faded into something of a lost decade. His comeback and rise to a beloved new prominence began in the 80s, writing more movie music with his third wife Carole Bayer Sager.

By the ‘90s, he was collaborating with everyone from Elvis Costello, in the 1998 collaboration album Painted from Memory, to Doctor Dre on Bacharach’s own 2005 album At This Time. Oasis, R.E.M. and Massive Attack all cited him as an influence, and The White Stripes released a hard-thumping cover of ‘I Don’t Know What to Do With Myself’ on Elephant.

Bacharach’s nostalgia-tinged status was cemented by appearances on all three of the Austin Powers movies, which all riff on just the kind of swinging ‘60s charm that Bacharach and his music embodied. In 2015 – a kind of culmination of appreciation for the man who had rarely sought frontman status – he even performed at Glastonbury, to rapturous welcome.

Following his death, tributes flooded in from fellow ‘60s pioneers, including Brian Wilson, who called Bacharach “a hero of mine”, and The Kinks’ Dave Davies, who said he was “one of the most influential songwriters of our time”. Such testimonies show the legacy Bacharach has left, which far transcends death-knell ‘easy listening’ or ‘elevator music’ labels that have consigned many of his solid fellow craftsmen to oblivion.

Bacharach’s songs stand with other standards of the Great American Songbook because they contain constant potential for reinvention. They are simple enough to allow for it, complex enough to deserve it. They seem likely to live a long while.

1 Comment

Great piece- reasons for his success brilliantly defined