Ah, Christmas. A twinkling tree and a roaring fire, a carol crooned and a mince pie munched, the air heavy with the smell of pine needle and mulling spice. It’s a time that we associate with warmth and cheer, hunkering down against the midwinter cold to the sound of Dean Martin and Aled Jones. Yet, for all the sparkle and jollity, something sinister lurks beneath the surface – something dark and cold and chilling. Something from beyond the grave.

Don’t get me wrong – I love a chestnut on an open fire as much as the next. But for me, Christmas simply wouldn’t be Christmas without a dose of ghostly terror. Late at night, after the firelight red on smiling faces, after the frosty silence in the gardens, comes the Christmas ghost story, an inviolable tradition at the heart of the holiday season.

Reginald Owen with ghost in a scene from the film ‘A Christmas Carol’, 1938. (Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Getty Images)

Like many a long-standing British tradition, this one is hard to unravel: why, at the cheeriest time of year, do we like to spook ourselves out of our skins? Popular belief ascribes the origin of the Christmas ghost story to Charles Dickens. It’s true, Dickens had a particular penchant for the festive spectre, embedding the tradition of reading ghost stories around the fire not just within his own family, but within the hearts of the nation. After the hugely successful publication of A Christmas Carol in 1843 (the same year that the first commercially produced Christmas card was sent), Dickens continued to write yuletide ghost stories throughout his life, and even published those written by others (including Wilkie Collins and Elizabeth Gaskell) in the magazines he edited.

It’s a particularly Victorian sensibility: a love for the macabre was all the rage in mid to late nineteenth century Britain – a result, in large part, of wider economic, cultural and technological shifts. The use of gaslights, for example, provided not only the ambient lighting for dark tales, but emitted carbon dioxide, which could trigger creepy hallucinations. Meanwhile, the mass migration out of villages and into urban centres was producing a sense of alienation without the need for toxins: servants feared spooks in the creak of every unfamiliar floorboard; masters heard ghosts in the quick footsteps of every frightened servant.

For these reasons, and others, the time was ripe for ghosts in the Victorian era – but the tale of the Christmas ghost story doesn’t begin here. The tradition has much older, folkloric roots that are – like many of our favourite yuletide customs – tied to the winter solstice. Gathering around the fire out of desperate necessity, people told stories to keep themselves entertained (and distracted from the biting cold) as the nights drew in. And in the days before literacy was widespread, the ghost story lent itself to this oral custom: anybody could summon up a spook, suggested by the dark, the cold, and the dancing shadows cast by the fire’s flickering flames.

But still, the question persists: why the desire to frighten ourselves at Christmas of all times? Halloween, at least, is devoted exclusively to spooks and spectres – there’s a rationale, a consistency – but why upset the festive apple cart with tales from beyond the grave? In Dickens’s Christmas fable, ghosts are there to serve a cheery purpose: for all the many spirits who waft in and out of the pages of A Christmas Carol, it’s a story, in the end, that warms the cockles like a brandy-soaked Christmas pudding – what could be more festive!

Reginald Owen frightened by D’Arcy Corrigan in a scene from the film ‘A Christmas Carol’, 1938. (Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-MayerGetty Images)

The same, however, cannot be said of the 1930s revival of the Christmas ghost story in Britain – a tradition that was largely resuscitated by the medievalist scholar and provost of King’s College, Cambridge, Montague Rhodes James – more commonly known as M. R. James. Though he penned ghost stories to amuse his erudite colleagues at Christmas parties, James’s ghosts are a far cry from the heart-warming spirits of Dickens’s fireside tales.

Drawing on his own scholarly (and often solitary) existence, James’s stories centre around lonely academics – usually antiquarians – holed up in dusty libraries or scaling the Suffolk countryside for long-buried artefacts. Again and again, his tales carry the same message: scholar, beware! (a caution he must have feared each time he unearthed another cobwebby fragment of mediaeval history). More often than not in James’s stories, ruffling the pages of the past disturbs some unpleasant spectre, who returns to haunt the bespectacled hero, killing them off in gruesome ways or reducing them to an incoherent bag of bones. What’s festive about that?

M.R. James’s ghost stories are the mainstay of my own family Christmas. Throughout the holiday season, we keep alive the tradition of reading these stories around the fire – from a dusty orange Penguin Classics edition, no less, that I found in a second hand book shop some years ago (and which looks as likely to summon spirits as any of the tomes in James’s tales).

We also ritually watch the BBC’s A Ghost Story for Christmas films – the 1970s adaptations of James’s (and a few others – including one of Dickens’s) stories, which aired every Christmas Eve between 1971 and 1978. These TV dramas are still genuinely disturbing: many a Christmas night I have crept up to my Victorian attic bedroom – much colder, much quieter than anywhere else in the house – afraid to peep out from beneath the covers, such is the chilling power of M. R. James. (Or maybe I’m a snowflake.)

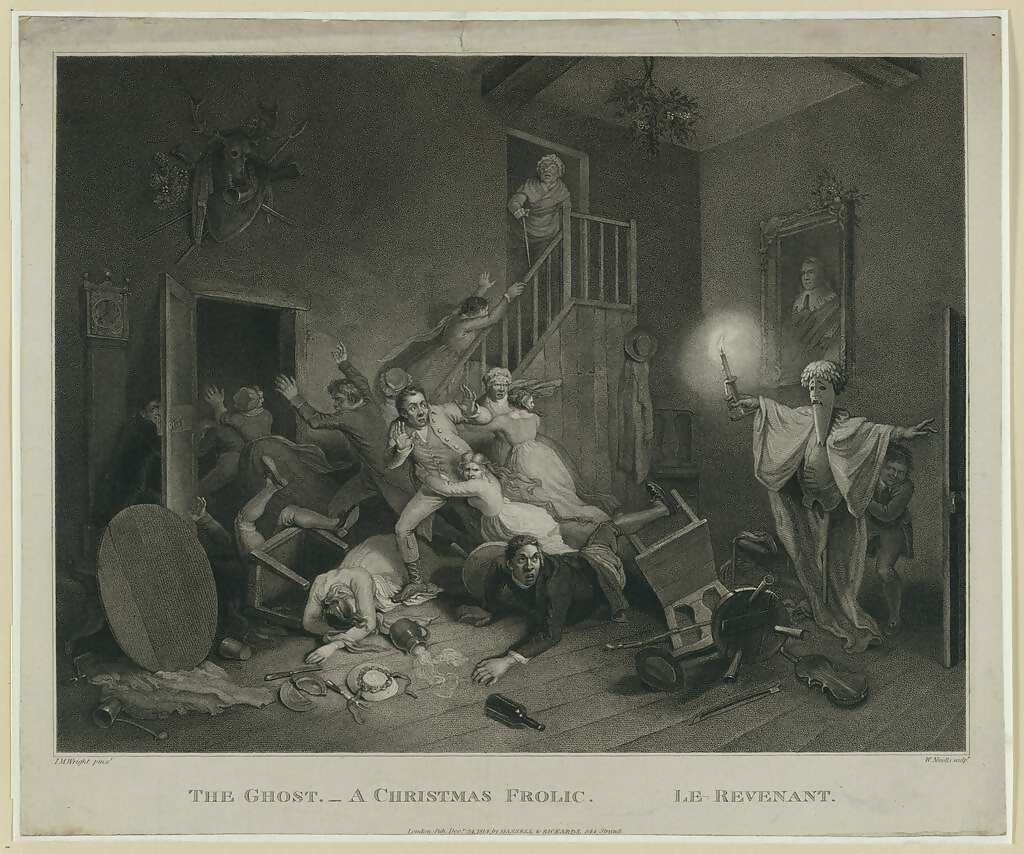

The ghost – a Christmas frolic – le revenantI.M. Wright pint/W. Nicolls sculpt.

The BBC revived its ghost story for Christmas in 2005, with a new adaptation of James’s A View from a Hill – a tale in which a classic Jamesian academic finds a broken pair of binoculars that turn out to reveal a mediaeval monastery to anyone who cares to look – at their peril. Every Christmas Eve since, a new, chilling film – usually (though not exclusively) an adaptation of a James story – has been released. Even though they pretty much guarantee a sleepless night, the revivified BBC ghost story is, to my mind, one of Christmas’s greatest gifts.

But still that niggling question: why? What have ghosts and ghouls, and all this fear and trembling, got to do with Christmas? Each era – whether Dickens’s Victoriana, James’s interwar Britain, the 1970s heyday of the BBC, or the post-millennium years – will have its own reason for digging the Christmas ghost out of its grave, but there is a certain something that each iteration shares: that sparkling, lametta-like thread that links Christmas present to a mythologised notion of the past.

Because we’re not talking contemporary Halloween horror here: there’s literally nothing festive about watching Saw or The Exorcist on Christmas Eve. But the ghost story – that’s Father Christmas for grownups. When we’re too old to believe in the man in red and his flying reindeers, we can summon the magical ghosts of Christmas past instead. And at a time of year when history and tradition are unashamedly de rigeur, nothing makes us feel more festive than imagining distant spirits from the safe and indulgent comfort of hearth and home.

So, whether it’s Dickens’s ghost of Christmas past, or James’s mediaeval ghouls, the Christmas ghost story exists in a misty, historical league of its own. Burying your head in a classic ghost story, only to look up and glimpse – ah yes! – a huge tree lit by an open fire feels nothing short of magical.

And if that’s not festive, I don’t know what is.