It’s a meal Louis Thomas loves to cook and the meal he cooks with the person he loves. But exactly what creamy hybrid of the original Italian dish do we Brits fail to notice we’re eating?

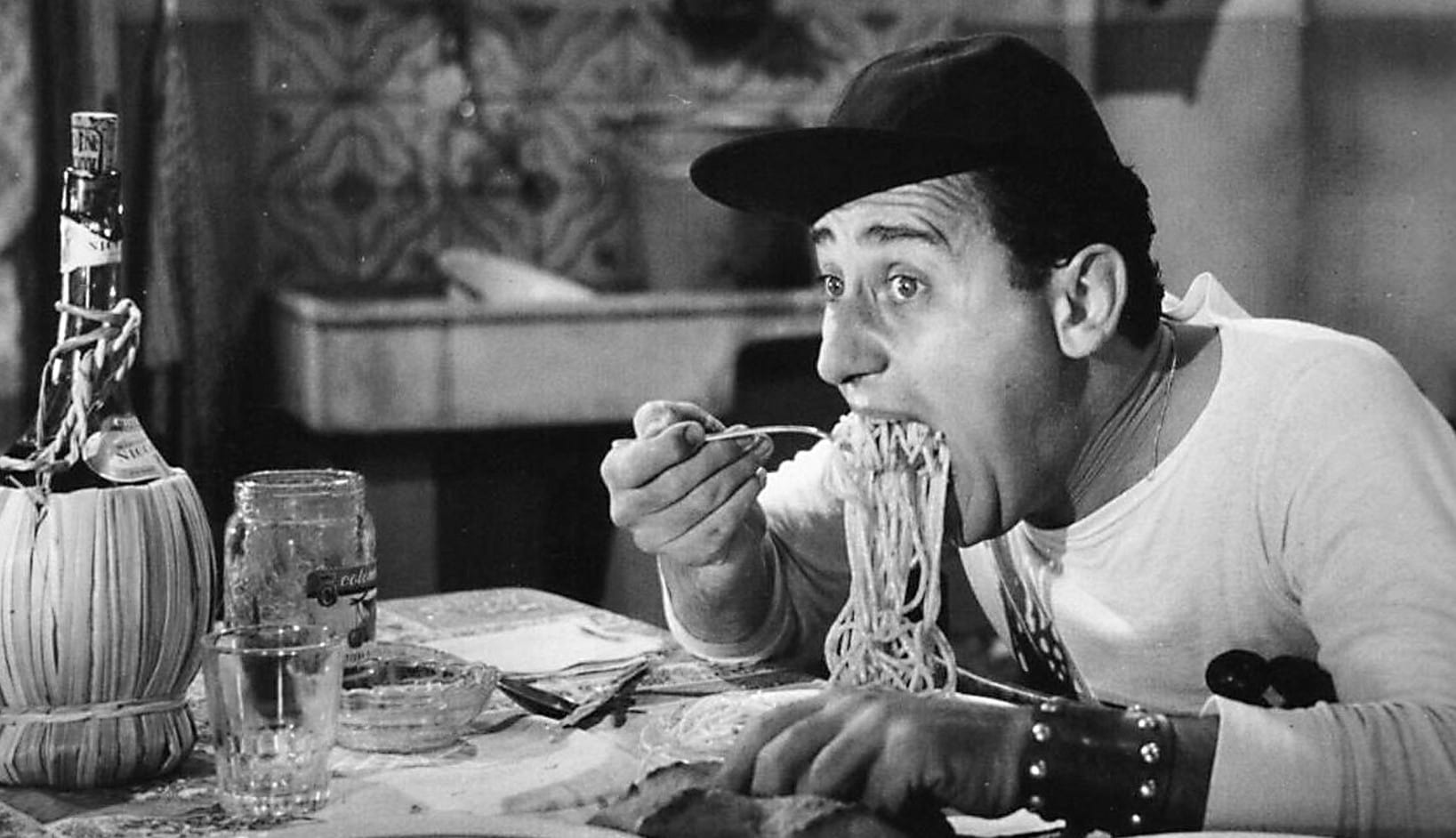

Alberto Sordi in An American in Rome (1954) heartily tucking in

Any trip to the Eternal City would be incomplete without being serenaded by this high-cholesterol symphony of rich egg yolks, the numbing heat of black pepper, the salty tang of Pecorino Romano (sometimes cut with Parmigiano) and unctuous guanciale. Carbonara is close to my heart in many senses. The Roman passion for maintaining the authenticity of this, the most sacred of the four classic pasta dishes of the city, quite possibly eclipses my own passion for the dish itself.

And yet, when surveying the menus of most Italian restaurants in Britain, one finds an unforgivable deviation from the recipe – the addition of cream, the pasta equivalent of a Hawaiian pizza. The Roman stance on this bastardisation is clear. When I emailed Chef Luciano Monosilio, known as the ‘King of Carbonara’, he described the original dish as a ‘perfect balance’ of strongly flavoured ingredients, and, if the egg and cheese mixture is correctly prepared, there is no need for anything else to make it creamy, indeed, Chef Luciano objects to alterations in the strongest possible terms: “It is useless (and sickening) to add more milk-derivative ingredients which would end up covering the characteristic flavour of carbonara.”

Chef Luciano (whose carbonara features at the top of the page) photo credit: Andrea Di Lorenzo

Sophia Loren lovingly twists spaghetti, 1955

However, though the authentic recipe for this dish seems clear, what’s decidedly unclear is its history, a culinary past as murky as the starchy pasta water integral to the silky sauce. The ‘carbon’ in the carbonara name could originate from a number of places. Perhaps the flecks of pepper are reminiscent of coal dust, or the association may stem from the early 19th century Carboneria, an undercover political movement who disguised themselves as charcoal burners.

As Professor Diego Zancani, author of ‘How We Fell In Love With Italian Food’, tells me: “It is rather difficult to find documents in this field.” Beyond appellative matters, the recipe’s development may also be explained in any number of ways – one such theory is that it was developed to satisfy American GIs stationed in Rome who craved the taste of bacon and eggs. Though it’s entirely possible that it was the GIs who brought it back to the States, the dish’s origins are probably somewhat older. It may well be exactly the sort of hearty meal that charcoal makers toiling in the woods of Lazio consumed to give them the energy for their labour.

Carbonara may have been developed to satisfy American GIs in Rome who missed bacon and eggs

Once carbonara was abducted from its native Italy it fell to prey to all manner of foul alterations, a trend which does not show any signs of stopping. In the absence of the correct ingredients and watchful Italians, the carbonara label has been stretched to its absolute limits. Gordon Ramsay’s recent ten-minute carbonara supplements the eggs with crème fraiche. I cannot tell if that’s equally as atrocious or worse than adding cream.

Though this is a comparatively minor offence when one realises that his recipe also includes mushrooms, chilli, garlic peas and parsley. I did not dare contact Chef Luciano about this for fear of giving him an aneurism. Ramsay’s mentor, Marco Pierre White, featured in a promotional video for Knorr stockpots in which he not only added cream but also shoehorned in his sponsor’s product by cooking the pasta in chicken stock, he even adds olive oil to the water and then has the audacity to mention that his mother was Italian. “There’s no real recipe” according to Marco – I would cite a boot-shaped country full of people who may disagree.

John F. Kennedy eating spaghetti during a ‘siuggorno’ in Rome

An examination of the history of adding cream explains why chefs still perpetrate this culinary crime. According to Professor Zancani, the use of cream in Italian restaurants in the Anglo-Saxon world can be traced back to the longevity of rationing after the Second World War. For a nation seduced by the Mediterranean musings of Elizabeth David, but unable to get hold of the proper ingredients, improvising the saucy emulsion with cream was the next best thing. There is also a practical benefit to using cream – it averts the risk, in the late Antonio Carluccio’s words, of “ending up with scrambled egg.”

In a bustling restaurant churning out mounds of pasta, it’s easy to see the benefits of adding cream to create a stable sauce, one that won’t end up as dry curds of egg suspended in a tangled nest of spaghetti. It’s possible to can tomato sauce for pasta, but tinned carbonara is seemingly unfeasible, though I have seen anaemic jars labelled as such in supermarkets and, upon inspection of the label, discover that they are an unholy fusion of cream and cheddar – fine for a mac & cheese, perhaps, but not for carbonara. It has to be made to order, and this requires skill. However, what started as a mere substitution evolved into something altogether very different.

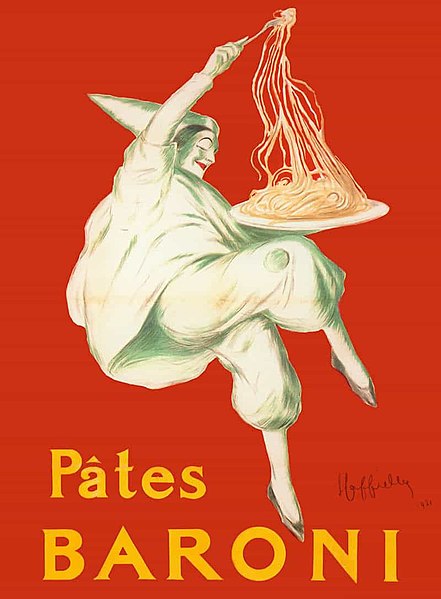

‘Pates baroni’ by Leonetto Cappiello, considered by many to be the father of modern advertising

I contacted a local Italian restaurant about why they use cream and the response was simple, and to the point: ‘the chefs only, and only ever, add cream to adapt to the English market as they prefer it that way’. Consumers got used to the cream and so it became part of the ‘Britalian’ recipe, to use Anna Del Conte’s portmanteau. Different cultures, different tastes. Indeed, cream is a recurring feature in British and American adaptations of Italian classics, from Alfredo sauce to pasta al limone – a striking tolerance for lactose has resulted in the ubiquity of dairy wherever a place can be found for it.

My parents describe a carbonara they regularly coveted in a London restaurant one which they practically had to wrestle with due to the addition of copious amounts of stretchy, oozy mozzarella. The haunting descriptions of this cheese monstrosity seem so far removed from the true carbonara that it begs the question of whether Britons expect something entirely different from this dish than Romans.

If you’re used to having cream, anything else is inauthentic, even the original. I suppose Pecorino isn’t to everyone’s taste either – the sourness and salinity of this sheep’s cheese is possibly a tad too much for some palates, which may explain why parmesan is often added, even in the old country. “It’s your choice” as Marco says. Trattorias with neon signs, red check table cloths and candles in wine bottles have offered generations of young lovers in this country their first taste of a gastronomic love affair which lasts a lifetime.

Frank Sinatra tucking in, 1952

Perhaps I’m too fascistic in my belief that once you add cream it ceases to be a carbonara at all, my zealous support of recipe purity blinkers my vision. I may be guilty of not practicing what I preach, given that I have fumbled towards the idea of alla carbonara countless times whilst not possessing the correct constituent parts. Guanciale proves elusive, and so I usually resort to diced pancetta, and occasionally, for my sins, even bacon. Though pecorino is slowly becoming more widely available in supermarkets, more often than not I have used straight parmesan. I confess, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, that my choice of pasta shape is also questionable. Purists would use spaghettoni or bucatini, and yet I have resorted to everything from rigatoni to tagliatelle, and devoured every exquisite mouthful of my criminal creation.

I draw the line at adding anything else other than approximations of the basic ingredients though, cream is the hill upon which I am prepared to die. Maybe I’m so vitriolic towards those who add it because I’m relatively good at avoiding scrambling my egg mixture, and so I see no need for it. I certainly daren’t go near the microwavable ready meal ‘spaghetti carbonara for one’ that has been lingering at the back of the freezer for eons, like a malignant dairy tumour. Thank God it’s only for one. Most great Italian dishes began by improvising with what you have, but in this modern day and age cream isn’t used as a substitute, it’s a wholly unnecessary addition that stops it from being a carbonara. Cream dilutes the intensity of flavour, and that I do not forgive.

This campaign might not be the best use of my time. I don’t even have the right to be so riled up; I’m not a Roman, no matter how many times I play up the ancient origins of my hometown of St. Albans. As has been established, I’m a snob and a hypocrite in my pursuit of authenticity given my use of inauthentic produce. Even Carluccio’s, the restaurant chain bearing the name of the late Godfather of Italian cooking in Britain, doesn’t stick entirely to the recipe, using grana padano instead of pecorino. Professor Zancani’s book discusses authenticity in relation to hybrid dishes, such as the ‘Britalian’ carbonara.

Italian soldiers in the Second World War tuck in

Truly authentic Italian delicacies are too niche to be widely sold, ‘only when travelling in Italy can one find truly authentic products’. I cook Italian, or in an Italian style at least, to capture some of the essence of the cuisine which has bewitched me. I don’t decide the way these things are done, I’m just grateful for what the Apennine Peninsula has given to Northern European cooking.

I’ve only had what could be properly described as a true pasta alla carbonara once, in the trendy, bustling Trastevere neighbourhood of Rome. It was everything I dreamt it should be and more, glistening with fat, bejewelled with pieces of fried guanciale, rubies in a golden crown. It’s so flavourfully fragrant, it’s like consuming a farm. But eating this, one of my very favourite meals, without my absolute favourite person left me feeling somewhat hollow, despite the huge amount of starch I had consumed. Eating it doesn’t take me back to Rome, but back to her, and my protectiveness of it may simply be a symptom of my infatuation.

I suppose it’s personal preference, and I’m sure there must be an Italian somewhere out there who adds cream, but I could never bring myself to do that, the moment I do it becomes something else. I yearn to return to Rome and sample Chef Luciano’s masterful execution of this simple, but challenging classic – an old recipe revitalised with technique and sophistication, one without a milk-derivative in sight. It’s a perfect dish as is, but one best paired with the perfect company.