The focus of their subsequent music film, 2012’s Shut Up and Play the Hits, was LCD Soundsystem and their rumoured last concert. The James Murphy-led outfit features prominently in their latest release, Meet Me In The Bathroom, which shines a light on The Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol, TV On The Radio, and others from the early 2000s New York music ‘scene’, and is based on Lizzy Goodman’s 2017 book.

Ahead of the documentary’s UK release this Friday, 10 March, we speak to Southern and Lovelace about piecing together the film using only raw archive footage from the time, the legacy of the period’s music, and their success as a duo.

Dylan, Will, let’s dive straight in: what drew you to the subject matter of Meet Me In The Bathroom and to Lizzy Goodman’s book?

Dylan: Obviously, we’ve made music documentaries in the past: the first one with Blur, the second one being LCD Soundsystem’s final, at the time, concert. We weren’t sure we were going to make another music documentary. We explored non-music ideas and then got the chance to read Lizzy’s book before it was released in the UK. It was such a page-turner and really transported us back to that time; we thought it would make an amazing film. We didn’t know what shape that would take, but we knew we were interested.

I think the main draw was that the characters are amazing – the stories of the musicians and their impacts on culture – but we were also drawn to the very specific time period; that point in our culture, just before the internet blew up, before everything changed in terms of technology, culture, politics. In a weird way, it’s a relatively innocent time, despite the fact that it’s quite a scuzzy scene at the beginning of the millennium. It was a moment – a very brief moment – just before everything accelerated out of control.

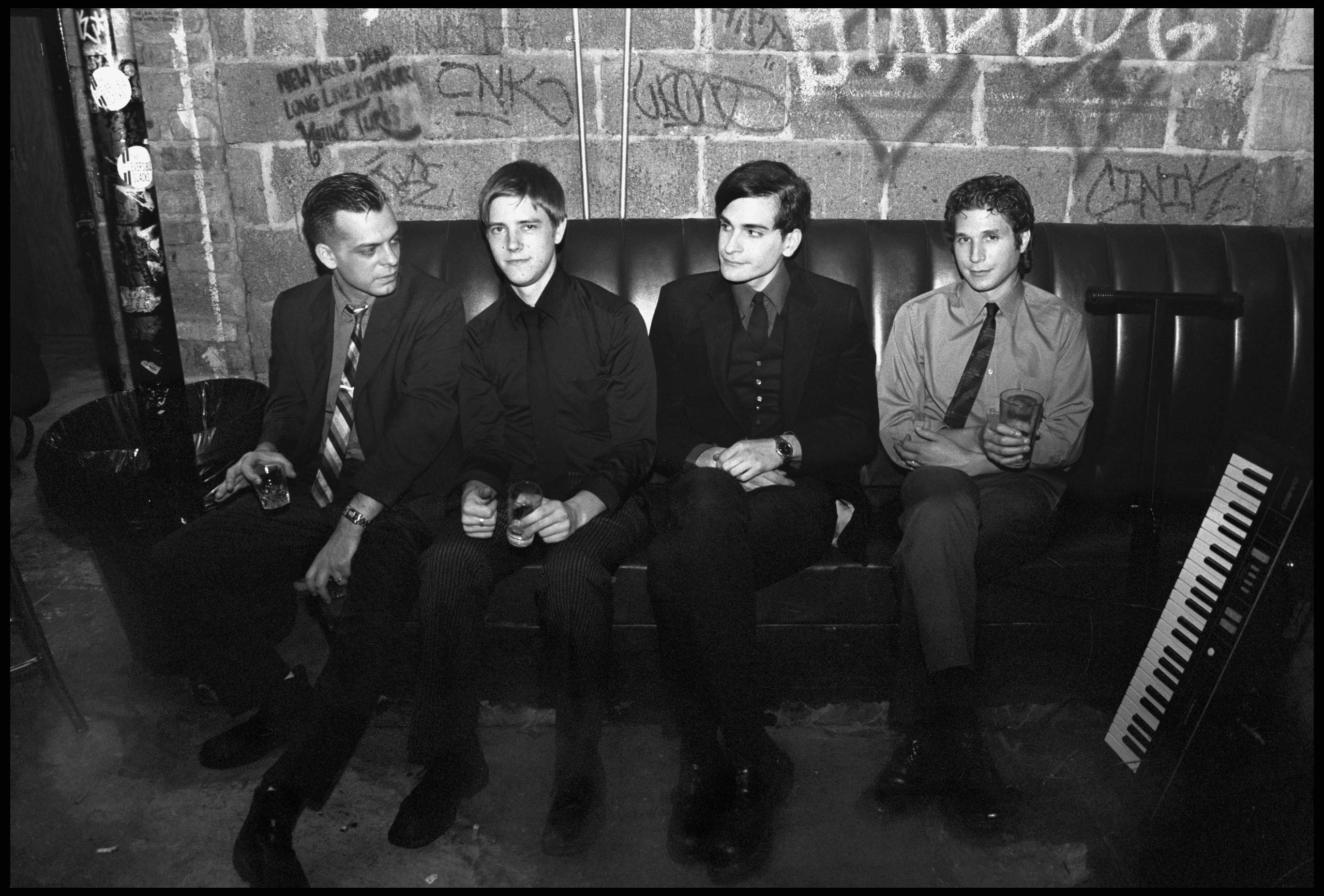

Photo: Colin Lane

It’s a pacey film created entirely from raw archive footage and audio interviews from the time. How did you go about collating all that material?

Will: We had an idea of what we were looking for, but it started properly in 2020, just before the lockdown. Once we all went into lockdown, it became a bit more of a DIY process to making the film. Dylan and I, the two editors [Andrew Cross and Sam Rice-Edwards], and the producers all dived into finding that archive ourselves. That involved a load of detective work, going on old forums, searching for gigs we thought were important; and going down rabbit holes, trying to find people who were filming, the photographers who were there. Lockdown helped, in a way, because people in New York had the time to look through old tapes.

Dylan: I think we got an archive we wouldn’t have if people hadn’t been in lockdown because everyone wanted distraction; it made people more reflective and open to going into the past. But it was a gargantuan task. We put down the film we wanted to make on paper and had written it in the way you’d write the outline for a film. But we didn’t know whether the archive necessarily existed to tell the parts of the story we wanted, so we had to throw the net out, and there was a lot to sift through.

Karen O of Yeah Yeah Yeahs. Photo: Emily Wilson Photography

Everybody in the team just kept ploughing on, chasing up leads. We could probably open a private investigations agency at this point because we became fairly pro at seeking things out. Will would spot a mini-disc recorder in the corner of a photograph, for instance, and then we’d locate the journalist who owned it and see if they still had the interview.

Were there any particular rabbit holes of enquiry that stood out when searching for archive footage?

Will: We spent a long time trying to find many things but never did. Then there were lots more exciting moments where you contacted a journalist because you’d read a really interesting interview they’d done with, say, [rhythm and lead guitarist for The Strokes] Albert Hammond Jr.. They would say, ‘Well, we haven’t got that tape, but I did do an interview with James Murphy back in 2001’, and you’d suddenly pivot because that recording was great. Someone found some general footage of a taxi travelling through New York, and that led us to a filmmaker who had also shot some gigs. All those sorts of coincidences led us to places.

It struck me in the film; you get the sense of these archetypal band situations: Julian Casablancas as this nervous perfectionist for The Strokes; Karen O as the female lead vocalist in a male-heavy world; LCD Soundsystem as this unexpected success story. How did you find a balance between telling the stories of the bands and the wider scene?

Dylan: New York at that time always gets talked about as a ‘scene’, and really that’s kind of a construct, probably of the British music press. I don’t think you would find Karen O hanging out with Julian or the Interpol guys sharing a drink with The Moldy Peaches. They were quite distinct and disparate. With the Brooklyn bands, it was more of an art-rock scene; with the lower-east side bands, it was more traditional rock n’ roll; The Moldy Peaches and the guys at The Sidewalk Cafe were doing their own idiosyncratic thing with the anti-folk scene; and then, James [Murphy], the late bloomer, stumbled into combining dance music and rock music, and created his own thing as well. So we were always aware the notion of a scene was sort of a transplant. The British music press always need something like that to get behind.

There was a vacuum at that point, and all of these interesting things were happening in New York, and it made sense to make it a scene. Obviously, [Lizzy Goodman’s] book is 800-pages long, and it’s very granular in telling the story. But the origin stories were the most interesting for us in the first three years. We found that they’re all coming-of-age stories – we wanted to use that as a guiding principle. You have Karen, the shy girl from out of town who comes to New York, discovers this scene, and creates a totally different one. James almost has this coming-of-age moment by accident. It’s just because he’s in opposition to all these other people that he finds the thing he’s good at.

Which of the artists’ stories surprised you the most as you delved further into them?

Dylan: I think the Interpol one. The Strokes opened the door for everybody else, but Interpol were very workmanlike. It took them longer to get to where they were going. They were the tortoise to The Strokes’ hare, I guess. But the intricacies of James [Murphy’s] story are also fascinating; he was an engineer at a recording studio and had been in a couple of kind of average bands before that. The turn of events leading to him being the last man standing is really interesting.

I get what you’re saying about the idea of a scene being something we retrospectively impose, but having made this film, what made that period so conducive to the number of successful bands that emerged?

Will: I think, in part, it’s definitely that specific time. It was pre-internet, or pre- the internet being like it is today, and pre-mobile phones being like today. It was right on the cusp of being how it always had been to promote a band and put your music out into the world whilst stepping into what it’s like today. I think that change in technology and culture is a really important reason why it played out the way it did.

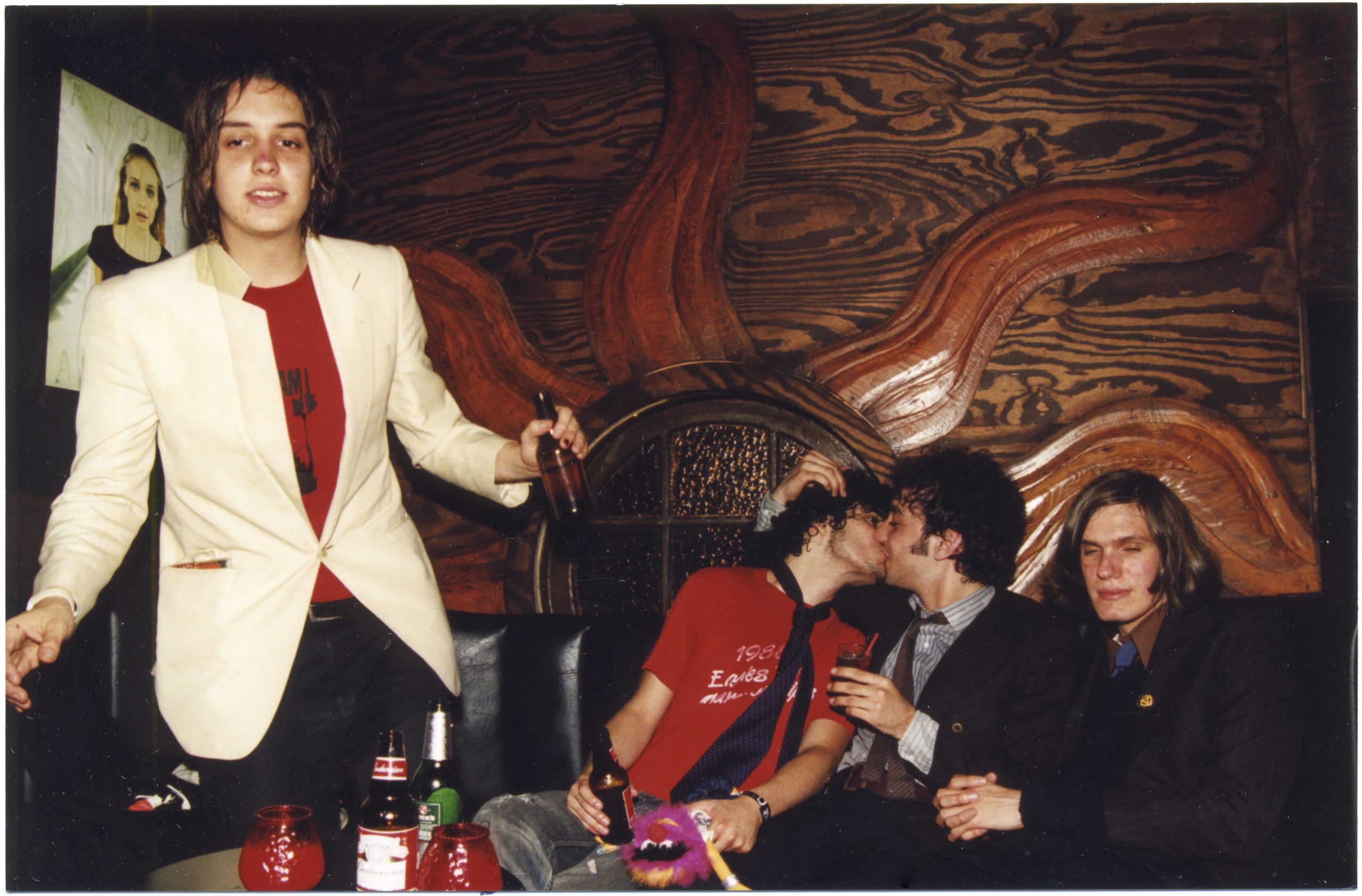

The Strokes. Photo: Piper Ferguson

Dylan: Several ingredients created the perfect storm. One is New York – its history, culturally – and the fact it’s this romantic, mythological place that attracts artists. I think, two, the fact there was a vacuum, culturally; in terms of guitar music, you had Limp Bizkit and that whole pop-punk thing, which was dreadful, and something needed to fill that gap. I think the third thing was the British press because they also needed something to fill a gap. And I think the fourth thing you can’t deny is the serendipitous things that make these driven individuals meet each other and create things that go beyond themselves. I think the film contains all of those to get you to the point where this happens.

You mention the internet, and the film also touches on the backdrop of 9/11, an event that birthed a decade of anxiety. What impact do you think that had?

Will: Clearly that had a huge impact on all the characters in the film; looking at the music and art they made before and after 9/11, it had a significant impact in different ways. We were very careful about how we included 9/11 in the film. We wanted to include it because it was part of the character stories. It wasn’t just for the sake of it.

We got old footage of Paul Banks [the lead singer] from Interpol on 9/11. He’d told us this footage might exist early on in our conversations, and then a couple of years later, we got hold of the footage. That was really emotional to see. It’s powerful footage of him on that day and helped connect our characters to that moment.

Photo: Colin Lane

You say you were talking to Paul Banks. What was your relationship with the bands in the making of this film?

Will: We knew James Murphy from our previous film [2012’s Shut Up and Play the Hits], but he was the only one we’d really ever had any contact with. So we talked to the bands and got to know them. They were very helpful in talking to us, telling us their story, and providing us with archive footage. But we didn’t know them, really, before making the film.

Dylan: Obviously, [Lizzy Goodman’s] book came out in 2017, so initially, some of the bands said, ‘Well, we’ve done this recently. We’ve told our story’, so a certain amount of diplomacy was involved to persuade them. When they heard how we were doing it, that it was going to rely as much as possible on the archive from the time and make it immersive and not too retrospective, they came on board.

We did some contemporary interviews towards the end, where we felt we needed to craft the story a little bit. They were supportive in providing archive footage, pointing us in the right direction, and making sure other people adjacent to them helped us. And then they were really supportive of the release in America. We were blown away that The Moldy Peaches agreed to reform for the premiere. That was just incredible.

Photo: Piper Ferguson

That must have been quite an extraordinary thing: the film you made actually led to a reforming…

Dylan: Yeah, hopefully, played a part in it. They were one of my favourite bands at the time, so I was just over the moon. They were so supportive.

The film begins and ends with the Walt Whitman poem, ‘Give Me The Splendid Silent Sun’. Why?

Dylan: We wanted to create a sequence at the start and finish that bookended it. That poem, and that reading, have an air of romance that makes New York a beacon to certain types of people. The opening montage features iconic cultural icons from the past: Warhol and Lou Reed, and all these figures are projections of this romantic, mythological idea of New York. And then the repetition at the end was almost us asking the question: ‘Have the people you’ve just been watching done enough to become part of that canon, or has the world changed too much for that to be possible?’

Photo: Ruvan Wijesooriya

With the film, we were trying to contrast the notion of mythological musicians and the way they’re elevated in the culture with the reality of being in the scene, which was quite messy for a lot of them. They shone very brightly for a very short time, and then the repercussions continue to this day.

Let’s say it is a “scene” for the moment. What do you think the legacy of it was?

Dylan: It’s really difficult to say because we consume music and interact with culture so differently now; everything is available to everyone whenever they want. And we know so much about people’s lives through social media. So it’s difficult to say whether there’ll ever be totemic artists – like whether you’ll ever have a Bob Dylan again, you certainly won’t have a Beatles again.

Courtesy of Universal Pictures Content Group

I think the legacy is The Strokes came out with a perfect debut album, and I don’t think anyone will ever take that away from them. I also think perhaps it might be the last time a musical scene emerges organically from a single location; maybe technology and the way the music industry is, and the way we consume music, has changed too much for that to happen in that way again. It doesn’t mean exciting things won’t happen. They’ll just happen differently. We asked ourselves the question: could this happen again?

Will: We did and didn’t come up with a succinct answer.

Definitely, it’s more of an essay question. As an award-winning duo, it’s safe to say you work well together. Many people might think directing is quite an isolating or singular experience, bringing one person’s vision to life, but what’s the secret to your collaborative success as a pair?

Will: On this film, it’s fair to say it was a whole team of us. We couldn’t have made this film without the two editors, Andrew and Sam, without Christian [Cargill] and Vivienne [Perry] and our producers. I think it was the most collaborative project we’ve done, partly because of the type of film we were making.

Dylan: I also think we’ve worked together for so long. We always have a clear idea of what we’re trying to achieve initially. I think it’s when you don’t have that idea that opposing ideas of what it could have come in. So I think it’s all about doing the work upfront and interrogating it.

Meet Me In The Bathroom releases in UK & Irish cinemas from 10 March.