From ancient catacombs and buried citadels to nuclear bunkers, our relationship with the underground runs deep. We’re descending below the surface, exploring overlooked worlds beneath our streets: what’s down there and what these spaces have to tell us.

When I started this series, I had just moved into a basement flat in Edinburgh. After years of living above ground, descending a dungeon-like stairwell to my front door was a new experience for me. But even stranger was the discovery others were living under me. If you have visited Edinburgh, you will no doubt be familiar with the city’s vertical street structure. From the medieval Old Town’s turreted skyline to how many buildings extend far below street level—sometimes up to two or three stories deep.

What is underneath Edinburgh?

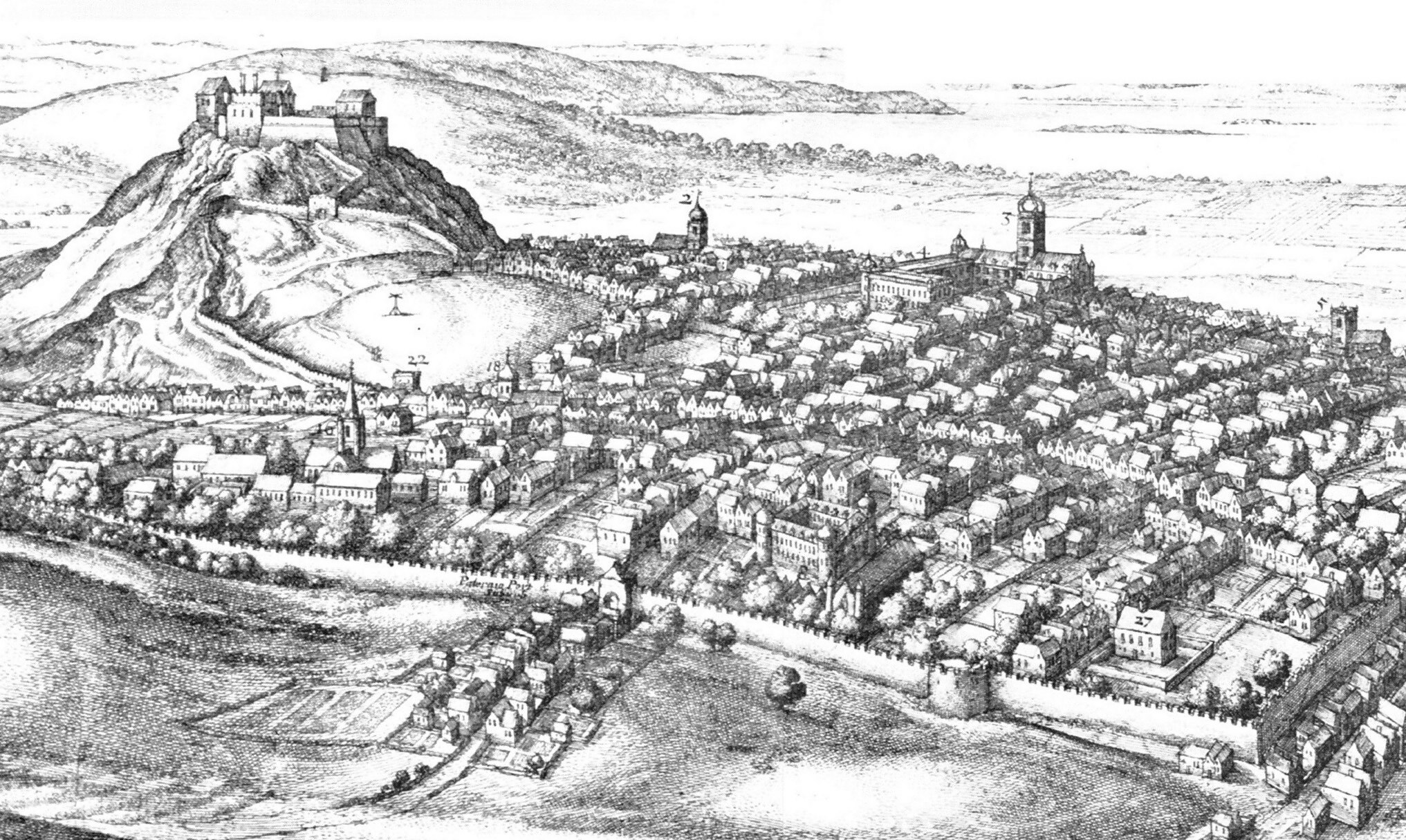

In fact, like so many places we’ve explored in this series, Edinburgh has a longstanding history with the underground. During the 17th century, the city suffered from significant overcrowding, forcing residents to live virtually on top of one another. This issue was partly due to the 24-foot-tall Flodden Wall that encircled the city, originally built to defend it against English invasion. With no space to expand outwards, houses packed tighter together. They climbed upwards to 10 or more stories high—creating the world’s first-ever ‘skyscrapers’—while down below, cellars and basements were converted into underground housing.

Edinburgh in 1670 century by Wenceslas Hollar (the Flodden Wall runs around the perimeter of the city)

In the 1600s, one of Edinburgh’s most vibrant and lively neighbourhoods was Mary King’s Close. The close, named after a local merchant burgess, is thought to have housed hundreds of people, with the warren of winding alleys and tenement houses now laying entombed beneath the Royal Mile. Unlike wynds (public pathways), closes were private streets locked up at night to keep out any undesirables. Residents of all social classes inhabited them: the wealthiest lived on the upper floors as they got the most light and least stench of sewage. The poorest lived on the dark, filthy ground floors—with multiple families sometimes occupying a single room.

When the Black Death struck Edinburgh in 1644, the closes were particularly hard hit, as their unsanitary and overcrowded conditions provided the perfect breeding ground for disease. While exact figures are unknown, it’s believed the plague wiped out a quarter of the city’s population. Although Mary King’s Close was partially demolished and buried in the mid-18th century, some residents continued to run their businesses in a strange half-submerged world before it was completely sealed up and deserted in 1902—mostly forgotten until its rediscovery a century later.

Mary King’s Close in Edinburgh

Meanwhile, as Edinburgh’s Old Town continued to decline into an increasingly dilapidated slum, it became practically segregated socially from the rest of the city. In 1865, the Scottish poet Alexander Smith wrote of one of the poorest districts:

“The Cowgate is the Irish portion of the city. Edinburgh leaps over it with bridges: the inhabitants are morally and geographically the lower orders. They keep to their own quarters, and seldom come up to the light of day. Many an Edinburgh man has never set his foot in the street: the condition of the inhabitants is as little known to respectable Edinburgh as are the habits of moles, earthworms and the mining population.”

As Smith describes, class divides were reinforced by the city’s ‘verticality’, with the poorest living a ghost-like existence beneath the streets. Indeed, the very language used to describe the underground comes with its associations: the terms “upper”, “lower”, and even “under” class have led to the equation of distance down into the earth with closeness to an animalistic or uncivilised being; the word “basement” derives from the word “base” which originates from the old French bas, meaning “low”, “lowly” or “mean”.

Although not underground in the literal sense, Edinburgh’s South Bridge—which crosses Cowgate—is often considered “underground”. Opened in 1788, entire “cities” formed in a series of windowless vaults behind its stone façade, complete with taverns, cobblers, cutlers, smelters, victuallers and milliners—all of which remained concealed from the bridge where the wealthy strolled. When deteriorating conditions caused traders to abandon the vaults in later years, the South Bridge became home to a new crowd: Irish immigrants fleeing famine, Highlanders seeking refuge from the Clearances, mercenary landlords and even bodysnatchers, who allegedly scoured the vaults for victims.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s description of the vaults in his 1878 book Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes gives a sense of what they might’ve been like at the time:

“… under dark arches and down dark stairs and alleys…the way is so narrow that you can lay a hand on either wall. [There are] skulking jail-birds; unkempt, barefoot children; [an] old man, when I saw him last, wore the coat in which he had played the gentleman three years before; and that was just what gave him so preeminent an air of wretchedness.”

![A view of Edinburgh from Bridewell (1822) [Scotland]](https://spaces.whynow.co.uk/2022/10/nbtow9bgth351.jpg)

A view of Edinburgh from Bridewell (1822)

Underground living around the world

If anything, these accounts confirm the deep-rooted fears of the underground and reflect the social divisions that were—and still are in many places—ingrained in the built environment. Today, in South Korea, for example, lower-class citizens often live in sub-basement homes known as Banjihas. In Beijing, a large population of mainly migrant workers (pejoratively known as “the rat tribe”) lives in cramped conditions in underground accommodation beneath the city. And in the Romanian capital of Bucharest, a generation of children has grown up in the underground sewer.

Yet as usable land becomes increasingly scarce in urban centres worldwide, subterranean space has come back into focus. Despite the unappealing aspects of being underground (such as the lack of natural light—quite a big downside considering sunlight’s significance to our health and wellbeing), it also has its benefits. As we’ve seen, underground spaces provide sanctuary from the topside world: practical if there is a war or nuclear catastrophe above; convenient in extreme weather conditions.

In Montreal, a 20-mile-long underground complex is an effective pedestrian network during the harsh Canadian winters. Likewise, underground malls in Singapore are used as alternative recreational and social spaces to escape the tropical climate. The underground spaces also have an advantage in energy efficiency as the ground functions as a thermal reservoir for interior temperatures; some have proposed that London’s lost rivers should be used to heat the city and cut emissions. The possibilities of the underground are seemingly endless.

Underground millionaire living complexes

Perhaps one of the more controversial phenomenons in recent years, though, has been the growing appetite for private subterranean complexes. We have already explored how nuclear bunkers are on the rise, with the super-rich investing millions into underground real estate reserved for the event of global catastrophe. But in cities like London, underground spaces are becoming not just a temporary retreat to wait out the storm but an extravagant extension of everyday life.

Professor Roger Burrows and researchers at Newcastle University have researched the phenomenon of ‘iceberg homes’ in London: deluxe basements that sometimes extend multiple levels beneath the ground. In affluent areas where planning restrictions make it challenging to extend properties laterally or add floors above, the only solution is often to build down. “Our new research now suggests that such developments are emblematic of how London is changing,” Burrows writes for The Conversation. “Along with residential high-rise luxury towers (“luxified skies”) sprouting up across the city, we are also witnessing an epidemic of ‘luxified troglodytism’—super-rich households extending their properties in a subterranean direction by way of basement excavation.”

The 2018 study, which aimed to map the “subterranean geographies of plutocratic London”, found 4,650 basements approved for London homes, including 785 large and 112 mega-basements between 2008 and 2017. Typically three storeys or more—or two storeys extending beyond the footprint of the house—these basements collectively boast 367 swimming pools, 358 gyms, 178 cinemas and 63 staff spaces. “We also found 14 car lifts, seven art galleries, two gun stores – and one owner who admitted to building a ‘panic’ room,” notes Burrows. One approved was a three-storey basement in Holland Park with an artificial beach. With fewer laws dictating what can be built underground, virtually anything is possible (so long as you have the budget to match).

Such deep-level excavations have inevitably wreaked havoc on nearby neighbours. Besides the noise, air pollution, and general nuisance they cause, deep digging also poses the risk of structural collapse. In 2017, The Telegraph reported that a £1m London home had collapsed “in a pile of rubble” as its owner attempted to construct a vast, two-story basement extension beneath the period property.

Tunnel End. This tunnel portal at South Lodge is where the Duke of Portland would have resurfaced after travelling underground from Welbeck Abbey. This incidentally is the nearest tunnel portal to Worksop Station contrary to the popular myth that a tunnel carried the Duke all the way to the station

It is worth noting that digging down among the rich and privileged is not a wholly new phenomenon. For the fifth Duke of Portland, William John Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, the cocooned comfort of the underground suited his reclusive personality perfectly. When he took over the estate of Welbeck Abbey in north Nottinghamshire in 1854, the Duke began an eccentric reign of excavation. Digging a labyrinth of tunnels beneath the grounds—and connecting a series of underground chambers stretching 24 km—he installed a ballroom, observatory and billiards hall. The Duke dug so many tunnels he’s believed to have partly inspired Kenneth Grahame’s Badger in The Wind in the Willows, who professed: “there’s no security, or peace or tranquillity, except underground.”

Badger from Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows

Badger—an old and stoic creature—is a respected resident of the Wild Wood. While giving Mole a tour of his sprawling underground chambers, he explains how the tunnels are the buried ruins of a formerly aboveground city engulfed by the forest. “But what has become of them all?” asks Mole. “Who can tell?” replies Badger. “People come—they stay for a while, they flourish, they build—and they go… But we remain. There were badgers here, I’ve been told, long before that same city ever came to be. And now there are badgers here again. We are an enduring lot, and we may move out for a time, but we wait, and are patient, and back we come. And so it will ever be.”

Throughout this series, we have descended into the hidden spaces below, from superdeep boreholes to nuclear bunkers to the shadowy nexus of the deep web. In unearthing its treasures and stories, we have seen how the underworld is a repository of our deep past, tracing our shared history to eras long before the dawn of humanity.

We have travelled through time and across continents, from the incredible stone cities of Cappadocia in Turkey to modern-day ‘iceberg homes’ of the ultra-rich. We’ve seen how the underground can provide sanctuary in times of turmoil and how it can just as quickly evoke our most primal fears.

Paying attention to the underground is vital for—like the Unconscious—it offers a mirror and unique insight into life on the surface. Look closely, and you’ll find an ever-expanding realm beneath your feet: out of sight but never entirely out of mind.