Matilda, Mrs Doubtfire, Pretty Woman: why is everything a musical? Mae Losasso explores the rise of the immersive experience of musicals – and our fascination with rehashing old works in new forms – and asks what it says about our contemporary attitude to art, entertainment and culture.

On my way to buy a ticket at Brighton station, I notice a poster for Pretty Woman: The Musical. I share a sardonic laugh with myself – then promptly forget about it. A few minutes later, while waiting for the train to Blackfriars, I catch sight of another poster – this time for Mrs Doubtfire, the ‘big-hearted and hilarious new musical’ set to grace London’s West End. Really? I board the train – but the musicals follow me inside: Back to the Future: The Musical (seriously?); Bonnie & Clyde: The Musical (oh, come on); Heathers: The Musical (is nothing sacred?!)

When I finally make it to London, I face the pièce de résistance, spelled out in bright lights across the Noël Coward Theatre is – wait for it –The Great British Bake Off Musical.

All these musicals begin to feel like Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds: every time you turn your head, there’s another one perched on a billboard and eyeing you quietly. Perhaps I’m a snob: the only musical I’ve ever seen is The Book of Mormon (a parody of the form), but it’s not musicals per se that I’m taking issue with. There’s a long tradition – from opera through vaudeville to Hamilton – of singing and dancing on stage, and my own tastes aside, I’ve got no problem with that. What’s odd is the compulsive regurgitation of existing works: can’t musical directors develop anything new anymore?

Of course, they can; there’s a perfectly cynical reason behind all these theatres’ decisions to keep putting this stuff on: people who want to make lots of money often don’t want to take lots of risks, and according to the (horrible phrase) ‘bums-on-seats’ logic, predictable shows are more likely to sell (and all this, while many of London’s smaller, independent theatres are closing thanks to funding cuts). That kind of risk assessment isn’t hard to grasp from the point of view of the theatres – what’s harder to swallow is the “I like Pretty Woman, so I’ll love Pretty Woman: The Musical!” mentality. If you’re going to spend money on an evening out, why would you want to see something you’ve seen before – minus Richard Gere and Julia Roberts?

“I’m bored; you’re bored; we’re all bored”’, writes William Deresiewicz in a recent article for Tablet, “by our books and movies and television shows, the endless blandness of the Netflix queue, by our music and theatre and art. Culture now is strenuously cautious, nervously polite, earnestly worthy, ploddingly obvious, and above all, dismally predictable”.

Read More: ★★★★★ Operation Mincemeat review | Deceptively exceptional

Deresiewicz blames wokeness for the erosion of art and culture – a line that I don’t buy (there are bigger, nastier forces at work) – but his diagnosis of the problem is pretty spot on. In pointing to the dismal predictability of contemporary culture, what Deresiewicz captures is how the culture and entertainment industries have fused, producing a kind of endlessly repeating simulacrum; a Groundhog Day (the musical?) lovechild in which we keep consuming the same stories over and over again.

This isn’t just a musical… This is The Great British Bake Off Musical 🍰 Rising in London’s West End in February 2023, this brand-new British musical is guaranteed to tickle your taste buds. Tickets on sale at midday – On your marks, get set… BOOK! #GBBOMusical 🧁 pic.twitter.com/BuKrG20ncG

— The Great British Bake Off Musical (@BakeOffMusical) October 18, 2022

But on top of the repetition, our apparently insatiable appetites for these musicals also say something about our diminishing attention spans and increasing struggle to be passive viewers. The recent fiasco at a performance of The Bodyguard musical in Manchester is a case in point: the show was forced to end early because audience members insisted on wailing along to the climax of ‘I will always love you’ and drowning out Melody Thornton’s vocals. On some level, the musical offers its viewers to be involved in the stories they know and love – to interact, sing along, heckle, whatever – rather than sit and stare quietly at a screen.

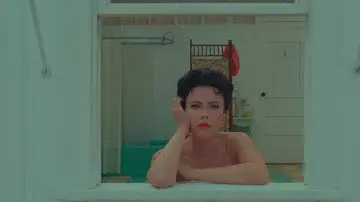

And this isn’t confined to the stage: something similar also seems to be happening in art. These days, we can’t just look at a painting on a wall – we have to be teleported inside Van Gogh’s Sunflowers or Dali’s The Persistence of Memory via an immersive ‘cybernetic’ experience. I haven’t been to one of these ‘metaverse’ exhibitions, but I can’t help but feel that the whole thing is a tacit acknowledgement that what matters most about a work of art isn’t the work itself but you, the viewer. As Deresiewicz observes, there’s a deep narcissism embedded in this approach to culture, “a demand that art affirm us, never threaten us, never make us feel inadequate or ignorant or small, echo back to us our precious little selves”. If that’s what we’re looking for, we might as well save ourselves the trouble and stay at home, where we can gaze into our mirrors for free – or would that be too passive?

Then again, there is a question mark over how authentic the passive gaze really is. Cinema and television are still young art forms – we’ve only been staring at screens for the last 100 years and doing it alone in our homes for almost half of that. If you look at art and theatre history, there’s a much longer tradition of immersion and interactivity. Think about Shakespeare’s bawdy plays at the Globe, where heckling from the audience was de rigueur. Or vaudeville and variety shows, where the audience was routinely invited to sing along or get up on stage and participate. Even baroque altarpieces – those enormous canvases painted by the likes of Titian and Tintoretto, at which we now like to stare meditatively in well-lit galleries – were made to adorn the walls of dark churches. These paintings may not have been interactive but were, in a sense, immersive: as they listened to the sermon, congregation members could palpably share in Christ’s suffering – or quake at the fires of the inferno.

Shaftesbury Avenue with Musical Theaters in Londoner West End

But today’s musical turn is different. Part of its problem is how it blurs the line between culture and entertainment. This may sound like an elitist argument, but there is a real necessity to separate the two, not to stratify high and low art (the very best is often a blend), but to keep art and culture away from the grinding machine of capital. Art has long had a relationship with money – there’s no sense in pretending otherwise. But it’s also one of our last remaining languages of resistance to an economic system that constantly finds new ways to overwhelm us. The rehashed musical – or the cybernetic painting experience – is one more way of lining some people’s pockets while keeping the rest of us anaesthetised and smiling.

At the rate these musicals are breeding, it’s only a matter of time before truly great cinema gets sucked up and spewed back out. Battleship Potemkin: The Musical? Thanks, I think I’ll take my chances with some side-street fringe theatre.