★★★★☆

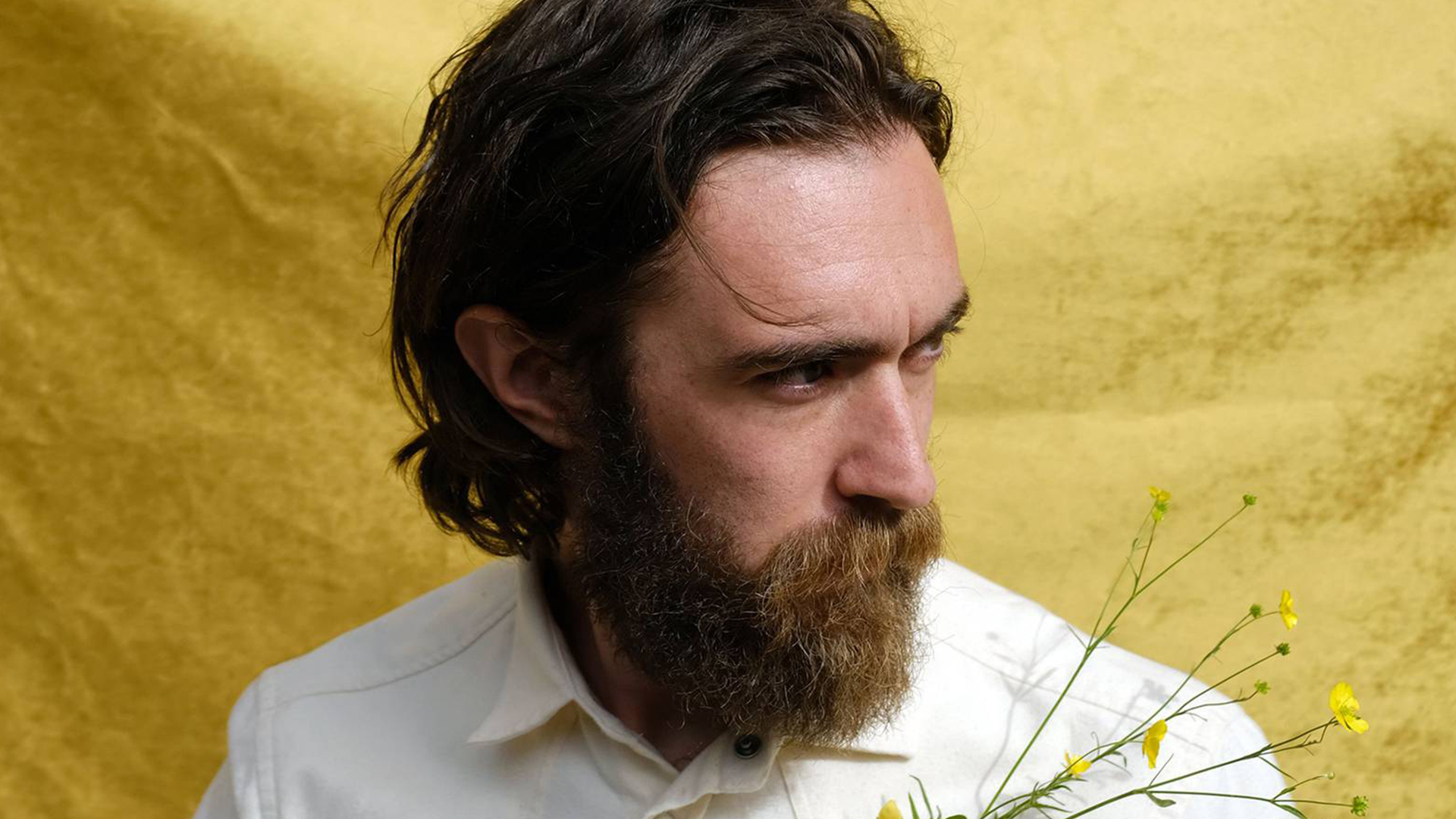

You think you know what you’re getting when it comes to Keaton Henson. Booming to cult fame back in 2012 with his debut album Dear, the musician could essentially be crowned the king of sad boys, gaining notoriety as his dark, poetic lyrics littered Tumblr.

Rarely performing live due to crippling anxiety, his mental health made him a mystery. It became the thing fans seemed to be obsessed with, as early albums Dear and Birthdays contained some of the most devastating lyrics ever penned (see ‘Party Song’ or ‘Sweetheart, What Have You Done To Us?’).

And while the world seemed to find poetry in the tortured artist’s plight, Keaton found what we all find in mental illness: life-stunting devastation. Running away from his own career in L.A. as Birthdays raised him to new levels of success, hiding from his manager, he’s since proceeded to take a million twists and turns into film scores, orchestral composition, performance art pieces and several attempts at retiring, with 2017 track ‘Epilogue’ really seeming at the time to be his final goodbye. But there’s one thing everyone always thinks they can expect from Keaton: sadness.

This isn’t to say that his latest album House Party isn’t sad; there are some devastating moments. But it’s purposefully different. Introduced as a somewhat concept album, focussing on a parallel version of Keaton – or an alter-ego that didn’t run from fame but raced towards it – House Party comes at the same internal conflict from an entirely different direction. And as opening track ‘I’m Not There’ throws you straight into the album with a classic rock, almost country-tinged track, that feels custom-made for a cheesy, 90s chick flick; fans that demand Keaton stay stuck in his own sadness will be thrown off his trail.

That’s what’s so beautiful about this album. Tracks like ‘Envy’ and ‘The Meeting Place’ especially see Keaton really going for it. He’s singing louder than he has, playing guitar like a teenage boy in a garage, making toe-tapping, body-swaying songs that shake off the stifling sadness of Dear.

Through this alter-ego, you can instantly feel a sense of freedom. Playing around with bigger sounds, introducing a full rock band to the album that we’ve never really heard on a Keaton Henson record before, letting himself create catchy tunes and fun melodies that welcome crowd reaction, it’s no wonder this album is also bringing about Keaton’s first live shows in years.

We have a lot to thank this album’s character for. While it might represent a different beast, a fame-hungry yet hollow, beaten-down rockstar, it’s brought Keaton out of his shell. And as someone that’s been lucky enough to meet the musician, I feel like it’s brought the person behind the public mask of sadness out too.

No one deserves to be trapped within their own mental illness, the tortured artist obsession does nothing for the individual and while Keaton may once have been the artist that soundtracked your teenhood depression, he doesn’t deserve to be stuck as such. House Party reflects his growth, his cheeriness, his humour, his long-held desire to have music be fun again. And he doesn’t deserve to be critiqued or met with disappointment that he’s managed that. Keaton Henson deserves the fun.

But that fun doesn’t mean Keaton’s lyricism takes a back seat. The deeply poetic, deeply specific lyricism that gained Keaton his legion of fans is still front-and-centre. A major standout comes on ‘Late To You’, the album’s sweetest moment, as Keaton drops the character to pen a song for his wife, with her voice backing him up.

Apologising for not getting to her fast enough, for all the stuff that’s weathered him before they met, lyrics like “And if you should ever tire of being my everything / I’ll understand and turn these hands to writing / But I can’t promise you won’t be in every word” more than deliver on the signature Keaton Henson emotional devastation.

Elsewhere, ‘The Mine’ falls completely into the horror of this alter-ego, reminding us that fame isn’t all fun and games. Harking back to some of his darkest work like ‘Charon’ or ‘You’, the stark and sparse verses navigating the lowest points in life, in lyrics like “I lost all my nails to the fight / If you will let me explain / I have aged and I’m frightened / By the sound of my thoughts in the night”; or the devastatingly simple “I hold myself to ransom / And can’t afford the fee”.

Despite being the closest to ‘old’ Keaton, after some of the rocking highs of House Party, the lows feel all the more effective. Booming to devastating life with a refrain of “they love me” draws similarities to the meltdowns in ‘Don’t Swim’ or ‘Kronos’. I don’t think anyone would’ve expected Keaton to tackle the emotional complexity of fame like this, luring you to a false sense of joy and then pushing you back into the abyss.

When it comes to sadness, we think it’s one-note. We think it’s a simple emotion, that depression is all grey, the tortured artist always hunched over his guitar, writing slow verses and moaning bridges. We complain it gets samey but just like the reaction to Lorde’s Solar Power, we hate it when they change – god forbid our favourite sad singers become happy.

On House Party, Keaton Henson plays in that contradiction. On his most effective album yet, it’s a fascinating look at fame, mental illness and the tortured artist trope. It traverses the fields from the day-to-day and his own personal experiences with anxiety, into the grand world of notoriety and what could have been had he not have run.

Now reaching a place of renewed confidence and passion for his art, I’m so glad he did run. While considering alternatives and alter egos, House Party is a testament to Keaton Henson’s personal artistic path; a feat of introspection on a whole new level and a fascinating take on his cultish fame and public persona.